In this series

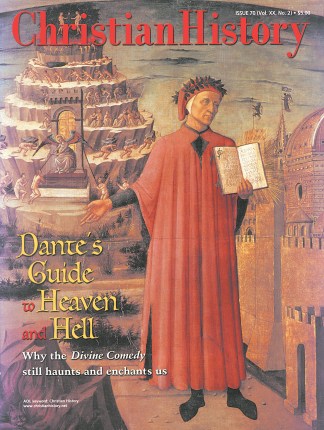

Shortly before giving birth in 1265, Dante's mother had a vision. According to fourteenth-century chronicler Giovanni Boccaccio:

"The gentle lady thought in her dream that she was under a most lofty laurel tree, on a green meadow, by the side of a most clear spring, and there she felt herself delivered of a son, who in shortest space, feeding only on the berries which fell from the laurel tree, and the waters of the clear spring, grew up into a shepherd, and strove with all his power to have of the leaves of that tree whose fruit had nourished him; and as he struggled thereto, she saw him fall, and when he rose again, she saw he was no longer a man, but had become a peacock."

This dream so startled her that she awoke and quickly delivered a son, naming him "Dante," which means "giver." Boccaccio adds: "This was that Dante granted by the special grace of God to our age. This was that Dante who was first to open the way for the return of the Muses, banished from Italy. 'Twas he that revealed the glory of the Florentine idiom. … that brought under the rule of due numbers every beauty of the vernacular speech. … and brought dead poesy [poetry] to life."

When Dante arrived, Florence had come to a crossroads between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Dante helped lead the city into a new era. Ironically, though, this poet who embraced the Muses and exalted Florentine speech spent much of his life in exile. Only after Dante's death did Florence want him back.

"Holy seed" on rocky soil

Dante's Italy was a tumultuous place. Kings and emperors battled with each other and the papacy, pitting church against government. Guilds and powerful families carved Florence into spheres of influence. Fortunes could be gained or lost overnight.

Dante's family, the Alighieri, was of noble origin but no longer wealthy. Still, Dante took immense pride in his ancestry. In Inferno XV, he claims descendence from the "holy seed" of the Romans who colonized Florence under Julius Caesar.

When Dante was still a child, his mother died and his father remarried. Dante speaks affectionately of a sister in the Vita Nuova, but it is uncertain whether she was his full sister or a half sister. He also had three half-brothers.

Like most educated men of his day, Dante studied grammar, logic, and rhetoric (the basic academic trivium, from which we get "trivia"), as well as arithmetic, music, geometry, and astronomy (the more advanced quadrivium). Boccaccio records that Dante also learned the arts of poetry, painting, and music. In the Vita Nuova, for example, Dante shows close familiarity with poems by Provencal (French), contemporary Italian, and classical authors.

Before Dante turned 18, his father died. Prior to his death, however, he had arranged for Gemma Donati to be Dante's wife. The couple had three or four children together.

Although Dante includes numerous accounts of his contemporaries, friends, and enemies in the Divine Comedy, he says nothing of Gemma. Some commentators take this as a negative reflection on their relationship, but the memory might have been too painful.

Love divine

The most important event in Dante's childhood was his first encounter with Beatrice Portinari at her father's house, when she was 8 and he was 9. In the Vita Nuova, Dante describes the event:

"She was dressed in a very noble color, a decorous and delicate crimson, tied with a girdle and trimmed in a manner suited to her tender age. The moment I saw her I say in all truth that the vital spirit, which dwells in the inmost depths of the heart, began to tremble so violently that I felt the vibration alarmingly in all my pulses. … From then on indeed Love ruled over my soul. … [and] I was obliged to fulfill all his wishes perfectly."

Ever afterward, Dante considered Beatrice the love of his life.

He next met her nine years later, when he saw her on the street dressed in white and accompanied by two other girls. She greeted him sweetly by name, and he was enraptured. A short time later, having heard his name linked with someone else, Beatrice passed him without speaking, and Dante mourned for days.

Dante and Beatrice never shared a love affair in any modern sense. Their meetings were no more intimate than passing in the street, and both of them married other people. Dante's feelings for her fit into the tradition of courtly love, in which the woman was idealized and eternally out of reach. A physical relationship with her was neither possible nor desirable.

Beatrice died when she was only 24, but Dante kept writing sonnets about her. Then, following a marvelous vision, Dante resolved "to write no more of this blessed one until I could do so more worthily." He challenged himself "to compose concerning her what has never been written in rhyme of any woman." The result was the Divine Comedy.

In both the Comedy and the Vita Nuova, Dante's love for Beatrice takes on supernatural attributes. She becomes a holy figure, comparable to the Virgin Mary. Beatrice comforts the poet, scolds him after he commits an unknown sin, and inspires him to write of his heavenly vision. Some consider her the symbol or embodiment of divine love.

The bread of strangers

Dante's life changed forever when he became involved in the war between two Florentine political parties, the White Guelfs and the Black Guelfs.

The parties had originally split over a family squabble, but they came to represent the division between the tacky, new-money Cerchi family (Whites) and the classier, old-money Donati family (Blacks). Dante was unfortunate enough to be a White, married to a Black, ascending to political office—Florence's priorate—just as conflict between the parties escalated into street warfare.

When the Blacks overthrew the Whites in 1302, Dante was swept up in the party purge. He was accused of barratry (the sale of political office), fined 5,000 florins, and exiled for life. He spent the rest of his years boarding with various patrons and writing. Though the Comedy is set in 1300, Dante wrote the entire work after he left Florence.

Dante wandered all over Italy and central Europe, tossed, he writes in Convivio, "as a ship without sails and without rudder, driven to various harbors and shores by the parching wind which blows from pinching poverty." Along the way, he learned (as described by Cacciaguida in Paradiso, XVII.59-60) "How salt the bread of strangers is, how hard / The up and down of someone else's stair."

In 1312 the leaders of Florence declared a general amnesty for political exiles. Dante could have returned to his home and his family, but he would have been forced to accept humiliating conditions. He declined the offer and wrote to a friend in Florence:

"This is not the way of coming home, my father! Yet, if you or other find one not beneath the fame of Dante and his honor, that will I gladly pursue. But if by no such way can I enter Florence, then Florence shall I never enter."

Eventually Dante settled in Ravenna, where, writes Boccaccio, "he was honorably received by the lord of that city, who revived his fallen hopes with kindly encouragement, and, giving him abundantly such things as he needed, kept him there at his court for many years." Dante's sons Pietro and Jacopo and his daughter Beatrice came to live with him there.

In the summer of 1321, while on a diplomatic mission to Venice, Dante became ill. When he returned to Ravenna, he lingered until fall, then died the night of September 13.

Ravenna buried its adopted son with honors, rebuffing Florence's request for the body. The city fathers believed Dante would not have wished to return. He had stated his opinion clearly in the full title of his masterwork: The Comedy of Dante Alighieri, Florentine by Citizenship, Not by Morals.

Perhaps Dante's greatest achievement, aside from sheer aesthetic triumph, is to make his readers ponder what they are truly living for. James Russell Lowell suggests:

"In the company of the epic poets there was a place left for whoever should embody the Christian idea of a triumphant life, outwardly all defeat, inwardly victorious, who should make us partakers of that cup of sorrow in which all are communicants with Christ."

"He who should do this would indeed achieve the perilous seat, for he must combine poesy with doctrine in such cunning wise that the one lose not its beauty nor the other its severity—and Dante has done it."

"As he takes possession of it we seem to hear the cry he himself heard when Virgil rejoined the company of great singers—All honor to the loftiest of poets!"

Bonnie C. Harvey has written a number of nineteenth-century biographies including Fanny Crosby (Bethany House), Charles Finney (Barbour), and Daniel Webster (Enslow).

Copyright © 2001 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.