CHRISTOPHER HALL BELIEVES in the Reformation principle of Scripture Alone. But he doesn’t think we should read the Bible alone—that is, in isolation from those who have gone before us.

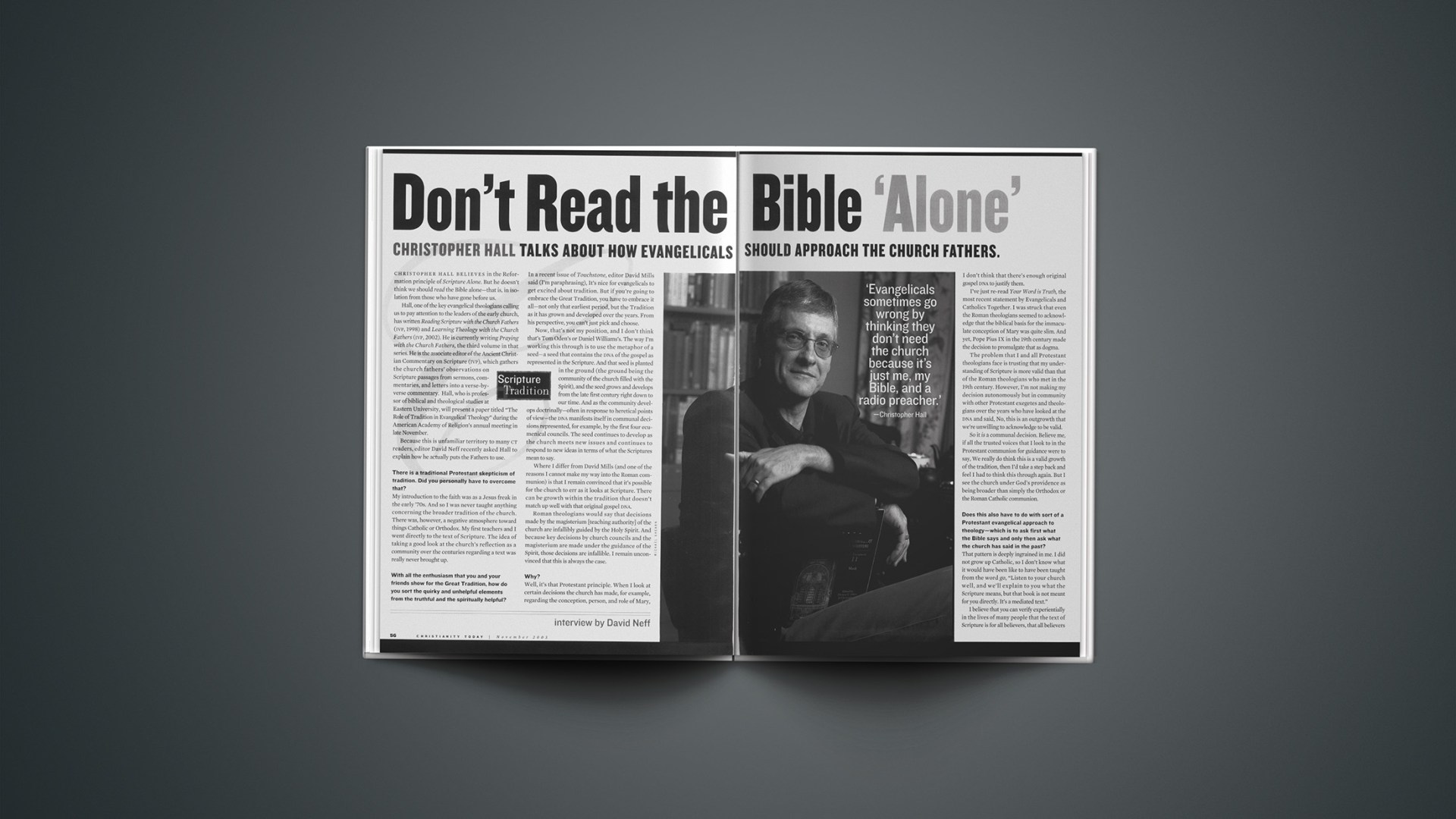

Hall, one of the key evangelical theologians calling us to pay attention to the leaders of the early church, has written Reading Scripture with the Church Fathers (IVP, 1998) and Learning Theology with the Church Fathers (IVP, 2002). He is currently writing Praying with the Church Fathers, the third volume in that series. He is the associate editor of the Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture (IVP), which gathers the church fathers’ observations on Scripture passages from sermons, commentaries, and letters into a verse-by-verse commentary. Hall, who is professor of biblical and theological studies at Eastern University, will present a paper titled “The Role of Tradition in Evangelical Theology” during the American Academy of Religion’s annual meeting in late November.

Because this is unfamiliar territory to many CT readers, editor David Neff recently asked Hall to explain how he actually puts the Fathers to use.

There is a traditional Protestant skepticism of tradition. Did you personally have to overcome that?

My introduction to the faith was as a Jesus freak in the early ’70s. And so I was never taught anything concerning the broader tradition of the church. There was, however, a negative atmosphere toward things Catholic or Orthodox. My first teachers and I went directly to the text of Scripture. The idea of taking a good look at the church’s reflection as a community over the centuries regarding a text was really never brought up.

With all the enthusiasm that you and your friends show for the Great Tradition, how do you sort the quirky and unhelpful elements from the truthful and the spiritually helpful?

In a recent issue of Touchstone, editor David Mills said (I’m paraphrasing), It’s nice for evangelicals to get excited about tradition. But if you’re going to embrace the Great Tradition, you have to embrace it all—not only that earliest period, but the Tradition as it has grown and developed over the years. From his perspective, you can’t just pick and choose.

Now, that’s not my position, and I don’t think that’s Tom Oden’s or Daniel Williams’s. The way I’m working this through is to use the metaphor of a seed—a seed that contains the DNA of the gospel as represented in the Scripture. And that seed is planted in the ground (the ground being the community of the church filled with the Spirit), and the seed grows and develops from the late first century right down to our time. And as the community develops doctrinally—often in response to heretical points of view—the DNA manifests itself in communal decisions represented, for example, by the first four ecumenical councils. The seed continues to develop as the church meets new issues and continues to respond to new ideas in terms of what the Scriptures mean to say.

Where I differ from David Mills (and one of the reasons I cannot make my way into the Roman communion) is that I remain convinced that it’s possible for the church to err as it looks at Scripture. There can be growth within the tradition that doesn’t match up well with that original gospel DNA.

Roman theologians would say that decisions made by the magisterium [teaching authority] of the church are infallibly guided by the Holy Spirit. And because key decisions by church councils and the magisterium are made under the guidance of the Spirit, those decisions are infallible. I remain unconvinced that this is always the case.

Why?

Well, it’s that Protestant principle. When I look at certain decisions the church has made, for example, regarding the conception, person, and role of Mary, I don’t think that there’s enough original gospel DNA to justify them.

I’ve just re-read Your Word is Truth, the most recent statement by Evangelicals and Catholics Together. I was struck that even the Roman theologians seemed to acknowledge that the biblical basis for the immaculate conception of Mary was quite slim. And yet, Pope Pius IX in the 19th century made the decision to promulgate that as dogma.

The problem that I and all Protestant theologians face is trusting that my understanding of Scripture is more valid than that of the Roman theologians who met in the 19th century. However, I’m not making my decision autonomously but in community with other Protestant exegetes and theologians over the years who have looked at the DNA and said, No, this is an outgrowth that we’re unwilling to acknowledge to be valid.

So it is a communal decision. Believe me, if all the trusted voices that I look to in the Protestant communion for guidance were to say, We really do think this is a valid growth of the tradition, then I’d take a step back and feel I had to think this through again. But I see the church under God’s providence as being broader than simply the Orthodox or the Roman Catholic communion.

Does this also have to do with sort of a Protestant evangelical approach to theology—which is to ask first what the Bible says and only then ask what the church has said in the past?

That pattern is deeply ingrained in me. I did not grow up Catholic, so I don’t know what it would have been like to have been taught from the word go, “Listen to your church well, and we’ll explain to you what the Scripture means, but that book is not meant for you directly. It’s a mediated text.”

I believe that you can verify experientially in the lives of many people that the text of Scripture is for all believers, that all believers are invited to that text, and that text welcomes them and can guide them and direct them.

However, having said that, I think evangelicals sometimes go wrong by thinking they don’t need the church because it’s just me, my Bible, and a radio preacher. Many think they don’t need to know the history of the Holy Spirit’s working within the church—and I’m including the Spirit’s work in the Orthodox church and the Catholic church. The Spirit has worked in all these communions. We’ve made too many mistakes by acting as if the text of Scripture has just been dropped out of the sky for this generation.

Speaking positively, I think that there is a movement of the Holy Spirit within the broad communion of the church today, drawing us back together to listen to one another carefully. I’m hoping for a cross-pollination to take place. And by God’s grace, we’ll continue to listen to one another.

The magisterial Reformers and later John Wesley made use of the teachings of the church fathers in a selective way. What can we learn from their selectivity?

There’s wisdom there. My approach to the Fathers is not uncritical acceptance. For example, as I’ve been writing Praying with the Church Fathers, the third volume in my series, I worked through Gregory of Nyssa’s sermons on the Lord’s Prayer. He reminds us that part of what’s involved in calling God “Father” is taking on the family resemblance. In a very strong, helpful way, Gregory calls his reader to holiness, to a life of virtue, to a strong rejection of evil, and to confession of sin.

However, when Gregory talks about holiness he occasionally makes me feel uncomfortable because he seems terribly optimistic about the human will. I think that there are aspects of Gregory’s thinking that have been, perhaps, deeply colored by Plato and by Plotinus. And the evangelical side of me asks whether Gregory is hearing the Scripture well at this point.

There’s wisdom in Luther, Calvin, and Wesley when they warn us against an uncritical acceptance of patristic teaching. However, I think that the evangelical weakness would be that if Gregory doesn’t say something exactly the way I want him to say it, using the kind of language I’m used to as an evangelical, then I’m apt to stop listening too quickly.

As I was working through these issues with Gregory of Nyssa, I was listening to a tape of James through Jude. It surprised me that this section of the New Testament sounds a lot like Gregory of Nyssa in its emphasis on holiness, its emphasis on the importance of a life filled with the fruit of the Spirit, in its warning against saying that you love God if you don’t love your brother. In other words, Gregory, at that point, is not only influenced by his philosophical training, but he is hearing tonal qualities in the text that I tend to be deaf to. So when I find myself reacting to the Fathers and saying, I think Gregory is off base at this point, I need to brake myself and ask, Am I reacting against them because they are too influenced by Greek philosophy? Or am I reacting to them because they’re hearing something in the text of Scripture that I don’t want to hear?

Some Protestants value our commitment to sola scriptura because new light can break forth from the Bible in every age. Can we expect new light today?

The great issues have been resolved: the natures of Christ, the relationship of the members of the Trinity, salvation issues, and so on. None of those great issues remains to be settled.

Nevertheless, we might well encounter issues that are raised in a modern context, or readings of Scripture that are proposed in a modern context, that call the church communally to reflect more deeply on what Scripture is saying.

In the middle of the 20th century, for example, the problem of evil took on new proportions because of the Holocaust.

That’s right. And that issue continues to be chewed on by theologians across the board. Hopefully, new light will come to the fore.

Also, I think that there will be some extended debate about whether God is passible or impassible. [That is, whether factors outside God cause him to feel pain or joy.] Many evangelical theologians have too quickly jettisoned impassibility. There needs to be more work done regarding what we mean when we say that God has emotions. What do the biblical writers mean when they speak of “grieving” the Holy Spirit? You can’t just put an equal sign between God’s emotions and human emotions, and I don’t think the biblical writers mean us to.

But I will say that when you come up with a new understanding, you’ve really got to convince me or I’m not going to change. You’ve really got to convince me that your reading of these texts is stronger than the way that the church has, for example, viewed God’s impassibility. And then a great discussion can go on if we can learn how to talk to one another about these issues without shooting at each other.

So you’re saying that “new light” requires a heavy burden of proof.

Well, yes. For example, God’s impassibility was strongly advocated by the church well into the 19th century. And when we got to the 20th century, theologians began to jettison that doctrine because of new concerns over the problem of evil. I’m not sure that was a good move. I think it may be possible to hold on to impassibility and still believe in a really strong, loving, compassionate God responding to evil.

Copyright © 2003 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere

Earlier this week, Roger Olson warned about giving tradition too much authority.

A new monthly CT column, the Ancient Christian Commentary on Current Events, debuted this week with a discussion on what the church fathers said about war..

Earlier Christianity Today articles by Chris Hall articles include:

Does God Know Your Next Move? | Does God change his mind? Will God ever change his plans in response to our prayers? If God knows it all, are we truly free? What does God know—and when does he know it? Christopher A. Hall and John Sanders debate openness theology (May 11, 2001, ff.)

What Hal Lindsey Taught Me About the Second Coming | At UCLA, amid war protests and police helicopters, teachings on an imminent end made a lot of sense (October 25, 1999)

Adding Up the Trinity | What is stimulating the renewed interest in what many consider the most enigmatic Christian doctrine? (April 28, 1997)