Journalists who covered the 2014 "origins" debate between creationist Ken Ham and evolutionist Bill Nye were able to avail themselves of two ready-made narratives about American evangelicals. One underscored the tensions between traditional evangelical beliefs and those of a modern secular society. The other highlighted evangelicals' presence and participation in American public life. Of course, the Ham–Nye debate offered fuel for both storylines at once.

Homespun Gospel: The Triumph of Sentimentality in Contemporary American Evangelicalism

OUP USA

208 pages

$34.53

Among journalists and scholars, the keys to understanding and interpreting evangelicals have long been their distinct theological beliefs and their values-based activism. Even many self-proclaimed evangelicals use these benchmarks to explain ourselves to ourselves. This is why we elevate figures like Billy Graham, a paragon of evangelical belief, and (take your pick) James Dobson or Jim Wallis, who together represent the spectrum of evangelical social action, to typify our movement.

But historian Todd M. Brenneman wonders if the beating heart of evangelical identity lies elsewhere, perhaps most centrally along the aisles of the local LifeWay Christian Store. In Homespun Gospel: The Triumph of Sentimentality in Contemporary American Evangelicalism (Oxford University Press), Brenneman shifts the conversation away from beliefs and actions toward feelings. He shows how popular forms of evangelical expression traffic in familial and tender imagery: God as father, people as "little children," and nostalgic longings for home and the traditional middle-class nuclear family.

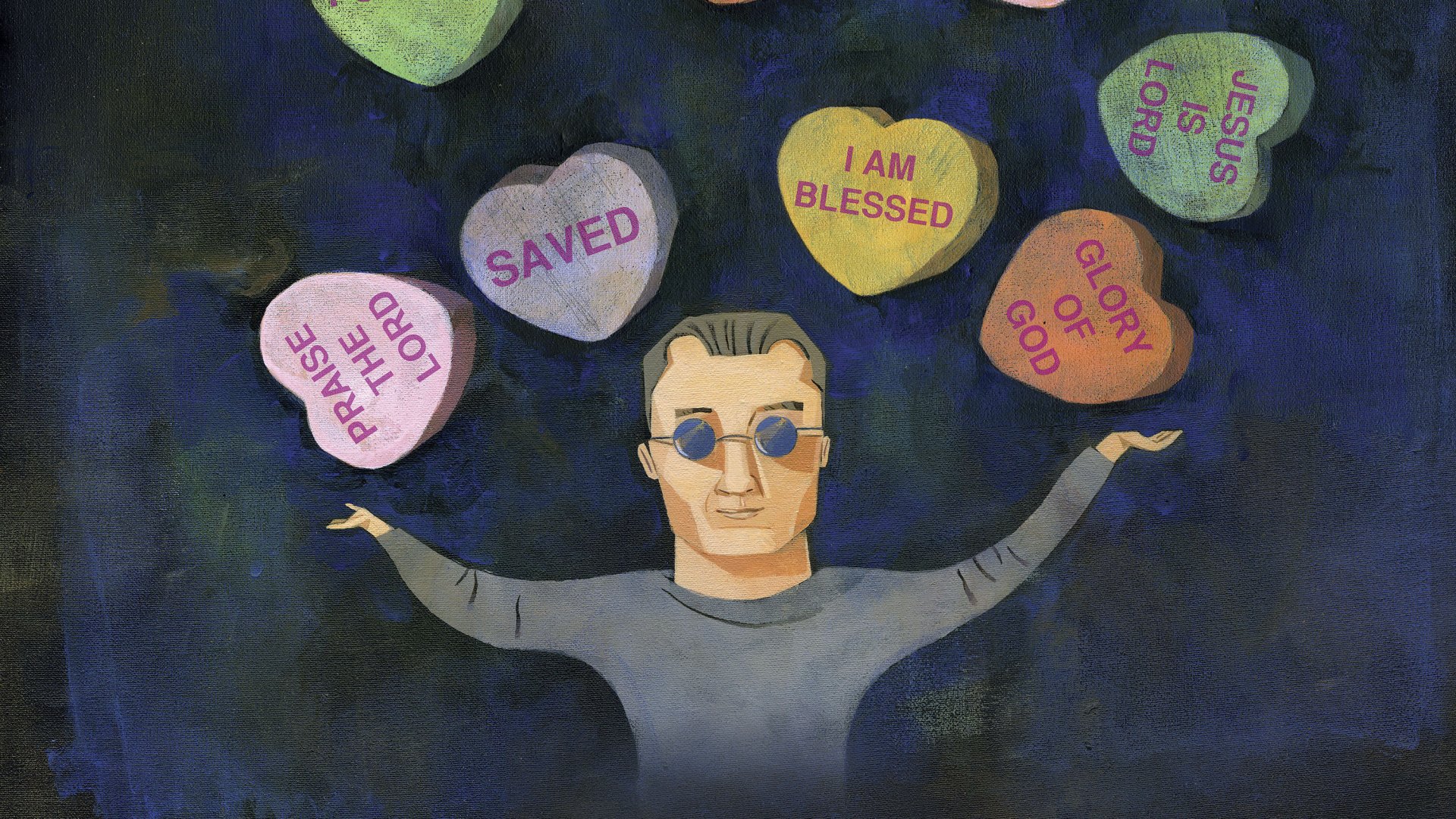

Brenneman draws compelling links between the worlds of religious consumer goods—from Christian CDs, DVDs, and books to toys, home decor, and devotional art—and the "core evangelical message" of God's love. These products, he argues, "construct religiosity as a practice of sentimentality instead of one of intellectual discovery." This is why, in our search for spiritual resources at LifeWay, we're likelier to encounter the works of tobyMac or Bob the Tomato than Abraham Kuyper or Alister McGrath.

'Culture of Emotionality'

Homespun Gospel could very well launch a broad reinterpretation of contemporary evangelicalism. By placing sentimentality at its center, Brenneman challenges some long-standing assumptions about the movement's contours and priorities. He argues that evangelicals' "culture of emotionality" and "appeal to tender feelings" subtly shape both their beliefs about God and their manner of engaging the modern world. Sentimentalism elevates personal emotional needs—and their satisfaction through divine help—to evangelicalism's highest priority.

Brenneman invites us to look closely at a popular yet understudied segment of evangelical discourse and commercial life. He focuses on the contributions of three celebrity pastors: Max Lucado, Rick Warren, and Joel Osteen. During the past 25 years, he says, these profitable "evangelical brands" have produced mountains of books and merchandise that reflect both the emotional and therapeutic appeal of evangelical teaching and the abiding popularity of sentimentalism.

Whether it's Osteen's invitation in Your Best Life Now to develop a "bigger view" of a God who wants nothing more than to ensure our happiness, or Warren's attempts in The Purpose-Driven Life to elevate the self-authenticating experience of feeling loved by God, these pastors make personal—even narcissistic—feelings the centerpiece of evangelical spirituality. As Lucado shows in his aptly titled children's book You Are Special, a Christian's greatest ambition is not to have a rich theological grasp of God's work as revealed in Scripture, but to rest in the simple fact that we are all his precious and dearly loved children.

It might seem, at first glance, that Brenneman's thesis would steer attention away from intramural squabbles over Christian doctrine and culture wars. But the genius of Brenneman's book is in reexamining old, familiar scenes through freshly adjusted lenses. Doctrinal disputes and cultural warfare may remain at the core of evangelicalism. But the stakes intensify when combatants frame the issues using emotionally charged imagery. In fact, Brenneman says, much of what passes for "evangelical discourse" in theology and public life is mere sentimentalized language that discourages careful reflection.

But does this assertion bear scrutiny? The evangelical world has plenty of popular voices marked by erudition and intellectual sophistication. How, for instance, does Brenneman account for the fame of pastors like John Piper and Tim Keller? Would he say that they draw on the same culture of emotionality—albeit with greater finesse—as Lucado and Osteen? Or are they rare exceptions that prove the rule? Readers can only guess.

To his credit, Brenneman does not succumb to what could easily become a mocking preoccupation with evangelical kitsch. He handles evangelicals with respect and treats sentimentalism as a category worthy of serious analysis. While many experts regard it negatively (as a manipulative tool used by the powerful to maintain their status), Brenneman recognizes a positive side. Citing philosopher Robert Solomon, who highlighted the power of sentimentality to "motivate individuals to constructive action," Brenneman holds out at least the possibility that evangelicals could do likewise.

Brenneman shows how 19th-century evangelical literature, hymns, middle-class domesticity, and revivalism used emotionality to motivate social action. He cites Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin and its role in mobilizing antislavery energy by appealing to feelings rather than intellectual or biblical arguments. These earlier evangelicals participated in a "shared sentimentality" that powerfully shaped public life.

Today's evangelicals, by contrast, devote themselves to an intensely private, therapeutic brand of sentimentality. As Brenneman points out, self-contained emotionalism often undercuts their high-minded talk of cultural transformation. By making the therapeutic self "the center of the world" and "the focus of God's attention," evangelicals risk obscuring "the structures of power and inequality that exist in American society." Ironically, emotional appeals to a transforming vision end up entrenching them deeper within their own emotions.

A Sturdy Foundation

As a work of scholarship, Brenneman's Homespun Gospel is both highly original and not quite original enough. Throughout the book, the connection between evangelical sentimentality and broader American sentimentality remains unclear. In what direction does the influence run? What, in other words, does Max Lucado have to do with Nicholas Sparks?

Are mother-daughter trips to the American Girl store or melodramatic "holiday specials" on the Hallmark Channel examples of evangelical nostalgia seeping into popular culture? Or have evangelicals simply bought into the sappier side of middlebrow American life while adding a thin layer of theological gloss? Brenneman could have done more to address these questions.

Nevertheless, Brenneman's superb analysis lays a sturdy foundation for scholars who eventually will. Besides setting a new and productive agenda for future studies of American evangelicalism, he invites evangelicals themselves to grapple with the problematic ways they experience the faith and pass it down to children. Strong and tender feelings toward God are vital, inescapable features of Christian faith. But Homespun Gospel reminds us that these same feelings come riddled with cultural and spiritual dangers.

Jay Green is professor of history at Covenant College in Lookout Mountain, Georgia.