Sandwiched between two major studio productions about biblical legends (Noah and Exodus) is an independent film about the rise and fall of the ancient Hebrew king, Solomon. While The Song lacks the artistic depth of Noah and the presumably jaw-dropping special effects of Exodus, it may have more heart and real-world value than either one.

City on a Hill

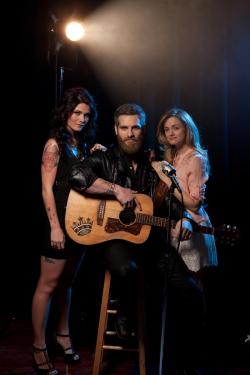

City on a HillAlso unlike its “Year of the Bible” counterparts, The Song recasts its characters in modern context. Solomon is reimagined as a modern-day singer-songwriter named Jed King (Alan Powell) who struggles to make a name for himself apart from being the progeny of his famous father, a renowned country music star (aptly named “David King”). In the midst of an identity crisis, Jed stumbles into a romance, courtship, and marriage to Rose (Ali Faulkner), a vineyard owner’s daughter.

The young couple has a “perfect” wedding night and storybook start—complete with poetic voice-overs drawn from the Song of Solomon. But after Jed writes a hit song for his new bride and is catapulted into the national spotlight, things get all Ecclesiastes. The pursuit of his thriving career leaves Jed wanting more. And the more he finds fame and success, the more he loses himself and his true love.

One of the glaring weaknesses of this film is the absence of even a single A-lister. In a year when biblical films feature a pile of notables, this film risks being overlooked. This gamble is apparent in a few awkward “rookie moments,” but is tucked away in mostly authentic, emotional performances. Overall, what the film lacks in pedigree it makes up for in honesty.

City on a Hill

City on a HillFrom drug and alcohol abuse to an extramarital affair with a sultry fellow performer (Caitlin Nicol-Thomas), Jed’s character wrestles with the meaning of meaning in a way that will make fans of faith films shift in their seats. But this risk turns out to be The Song’s greatest strength. It is willing to “go there,” to address the messiness of love and life without leaving all the tough stuff on the cutting room floor.

As executive producer and pastor Kyle Idleman said, "I think the church often hides under the covers, so to speak, when it comes to the issues of love, sex, and marriage, and by doing so popular culture continues to shape how we think about these subjects. It seems like it might be good for [the church] to step back and ask the question, 'How's that workin' out for us?'"

Like Idleman, I prefer a PG-13 flick that walks headfirst into a difficult conversation than a unrealistic, G-rated family film that tiptoes around a tough issue any day.

Religious audiences may also be surprised to find that there is little overtly spiritual content in this “faith film.” With the exception of one subtle and almost ill-placed reference to “someone who loves you enough to die for you” by Powell’s character during a performance at the “American Roots Music Awards,” all God-talk is limited to sparsely-placed narration quoted from biblical poetry. Secular audiences will probably never catch the subtle scriptural nuance woven into the script and soundtrack. Only the biblically literate will catch the cleverly hidden nods to the story of King David and Bathsheba, the “rose” of Sharon, and dozens of subtle references contained in the lyrics of Jed’s songs. (Look for Solomon’s famous judgment to “split the baby,” and the romantic language of Song of Solomon in “The Song” Jed pens for his wife.)

City on a Hill

City on a HillIf you want a heavy-handed evangelistic tool along the lines of Courageous or Fireproof, save your money. This film is not that.

Rather than convert audiences, The Song seeks to convince them that they are not alone in their troubles. Which is why I suspect most viewers will see themselves in this story. The husband who’s guilty of straying; the wife who chooses her children over her marriage; the son or daughter searching for his or her own identity; the strong woman who refuses to be abused; the pursuit of success and notoriety at the expense of all else—and, of course, the hope that redemption is possible amidst the muck and mess that life inevitably drags through all of our front doors.

City on a Hill

City on a HillBy blending together Song of Solomon and Ecclesiastes, The Song gives us something very Proverbs-like. It forces audiences to ask probing questions about life and love. It grapples with timeless, tough topics without pulling punches. But, most of all, this film reminds us that pursuing anything outside of the Source of true meaning is—as both Solomon and his modern counterpart say—“a chasing of wind.”

Jonathan Merritt is senior columnist for Religion News Service and author most recently of Jesus Is Better Than You Imagined (FaithWords).