A couple of months ago, burdened by ISIS violence, Ferguson, Ebola outbreaks, and Nigeria kidnappings, I walked a few blocks over to attend a neighborhood association meeting.

It felt uncomfortably quaint, trivial compared to the horrendous news that week. An elderly lady complained about her neighbor parking too close to her driveway. People argued about zoning ordinances with amusingly nerdy earnestness. There was a budget report about an ice cream social. It felt retro somehow, shockingly devoid of irony.

When I got home and my husband asked how it went, I could only describe it as “refreshing.” As global problems raged, all so very out of my control, there was something humane, empowering, and hopeful about sitting in a room with people debating traffic flow on Morrow Avenue, people who cared enough to give up their Monday nights to make some small difference where they live.

I told him the meeting was like an older, slightly grumpier version of Parks and Rec.

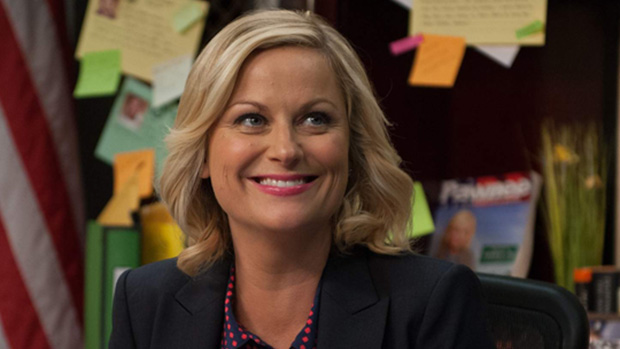

In the midst of its great comedy, the Emmy-nominated NBC sitcom Parks and Recreation offers a prophetic voice that urges us to consider again what it might look like to be peacemakers and culture-shapers. In a society marked by cynicism, abstraction, and hyper-mobility, Leslie Knope acts with genuine passion (even to the point where it’s a little awkward) and seeks the common good in concrete, small ways. She stays put and loves her community against all odds. Truth be told, binge-watching Parks and Rec (now in its final season) probably, on some level, prompted me to attend my neighborhood association’s monthly meeting for the first time.

In Catholic social thought, there’s a concept called subsidiarity, which suggests that political decisions should be made and implemented at the smallest, least centralized level possible. Based on the idea that we make wiser community decisions when we know the names, faces, and stories of those whom we live among and serve, subsidiarity reminds us to reject abstraction and remain as “human-scaled” and “person-centered” as possible.

In short, we can best serve a place if driven by love, and love must be personal and small enough to keep its feet on the ground. Leslie Knope’s most profound political motivation is love—love for a people and a place. She finds joy in battling raccoons and cleaning up rivers. And her joy is contagious—her co-workers (even the most cynical among them), her town, and we who are watching can’t help but be swept up in it.

E.F. Schumacher’s famous book on political thought, Small is Beautiful, includes a story about someone asking how, in light of massive global crises and change, we might respond politically. Schumacher replied that we should begin by planting a tree. One tree. In one place. Schumacher was making a point; he wants us to reengage where we are, not to wait passively for a solution to come from an abstracted political fiction like the nation-state. (This human-scaled thinking may contribute to our steady confidence in local government, even as trust in federal government declines.)

It is not that larger political communities should not exist. They are, at times, very necessary. Yet the notion that “small is beautiful” challenges the assumption that things are better when bigger, more centralized, and more technocratic. Ms. Knope (or, formerly, Councilwoman Knope or possibly the future Madam President Knope) is no small-government conservative. Yet, even while working for the federal government this season, she has remained focused on her particular, quirky, beloved community of Pawnee: its land, its tradition, its heroes (“Bye, Bye Li’l Sebastian!”), its waffles, and its people. Perhaps part of what it means to live incarnationally is to embrace where we are locally. Wendell Berry reminds us that, “No matter how much one may love the world as a whole, one can live fully in it only by living responsibly in some small part of it." Of course this should not mean that the rest of the world be damned—it’s important that we give energy, resources, money, and prayer to those organizations who work for peace and justice in far-away places. But I’ve realized I’m more likely to donate to an organization combating persecution in the Middle East or retweet about pacifism or advocate against abortion than talk to my neighbor—an elderly widower who it took me over 6 months to get up the courage to walk next door and meet.

The church is Christ’s agent of redemption in all the earth, globally, mysteriously, and cosmically, and yet, this work of redemption often looks small, ordinary and local, meeting our neighbors, planting trees, working for good in ways we can where God has placed us today.

In his book, The Christian Priest Today, Michael Ramsey sums up how God himself reveals his beauty in smallness:

Amidst the vast scene of the world's problems and tragedies you may feel that your own ministry seems so small, so insignificant, so concerned with the trivial. What a tiny difference it can make to the world that you should run a youth club, or preach to a few people in a church, or visit families with seemingly small result. But consider: the glory of Christianity is its claim that small things really matter and that the small company, the very few, the one man, the one woman, the one child are of infinite worth to God. Consider our Lord himself. Amidst a vast world with its vast empires and vast events and tragedies our Lord devoted himself to individual men and women, often giving hours and time to the very few or to the one man or woman.

Leslie Knope’s loyalties spring not from political parties or ideals, but from people. Because of this, she’s able to join forces with those who are very different from her. We are better for having watched her and anti-government Ron Swanson spar, debate, conflict, reconcile, love each other, and work together for the betterment of their town. In a culture where “partyism” is on the rise, where 49 percent of Republicans and 33 percent of Democrats reported that they would be displeased if their child married someone from the opposing party (up from 5 percent in 1960), this kind of on-screen friendship sounds a note of hope.

Recently, I was asked to be part of a neighborhood committee to get bike lanes and sidewalks on a busy street. I don’t know the political leanings or beliefs of others on the committee, but it doesn’t much matter because our project is small, local, and personal enough that we can simply be neighbors, figuring out how to help kids walk to the park or cyclists get to work a little more safely.

Ultimately, Leslie Knope’s politics rise from a deep sense of longing to see her hometown thrive. We’ve watched her get frustrated with the people of Pawnee; we’ve seen her criticized, scapegoated, and recalled as councilwoman; and still, she stays committed to her friends and her city. She continues to work for its shalom in concrete and creative ways. She has thrown her lot in with the people of her weird little Indiana town and, as she said so eloquently in a campaign speech, she “isn’t going anywhere.”

Whatever Ms. Knope goes on to do, her passions, community, and politics grow from deep roots in Pawnee soil. The prophet Jeremiah reminds us to “seek the welfare of the city” where God has placed us, for “in its welfare you will find your welfare.” Leslie Knope would likely repeat the sentiment and has sought her city’s welfare, joyfully and hilariously, for seven seasons. May we learn to do likewise, beginning wherever we are.

Tish Harrison Warren is a writer and a priest in the Anglican Church in North America. She and her husband work with InterVarsity Graduate and Faculty Ministries at The University of Texas at Austin and have two young daughters. She writes regularly for The Well, InterVarsity's online magazine for women. For more, see tishharrisonwarren.com or follow her on Twitter at @Tish_H_Warren.