Update: Shortly after we posted this interview with the founder of a Kathmandu-based clothing company Purnaa, Nepal suffered a devastating earthquake. Purnaa has since verified that all its staff survived. For more on the disaster and relief efforts, please see CT's Gleanings blog.

Two years ago today, an eight-story commercial building near Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, collapsed, killing more than 1,100 workers. The deadliest garment-factory accident to date, it is only one tragedy in a long history of worker exploitation in an industry known for long hours, low wages, child labor, abuse, and unsafe conditions.

In neighboring Nepal, Katrina Bryant, cofounder of social enterprise Purnaa, is working to prove that the garment industry doesn’t have to be that way. In 2013, Bryant moved with her husband and two young children to Kathmandu to start a manufacturing company that could empower its workers, be sustainable for the planet, and still remain profitable.

A full-service manufacturer, Purnaa works with designers and brands around the world that are willing to pay the true cost of their products to ensure an ethical supply chain. At least half of Purnaa’s employees come from exploited or marginalized backgrounds; all receive fair wages, generous benefits, and a safe and dignified work environment. This holistic approach means employees get everything from leadership training to regular vision checkups. Plus, Purnaa reinvests all of its profits into the employees and the social mission.

I first met Bryant several years ago when her husband was working for the social enterprise my husband co-founded. She spoke with me by Skype, then phone, then Skype again (globally, Nepal ranks 167th in Internet penetration) about her vision for change for the garment industry and the country.

Where did the idea for Purnaa come from?

In 2012, [my husband] Corban was working with a great company called d.light in India and seeing how business could be used to address real issues facing people at the bottom of the pyramid. It doesn’t have to look like charity to help the poor. And at the same time, we were hearing about human trafficking issues in Nepal, which is where I spent eight years of my childhood because my parents were working there.

While in Delhi, we met a South African guy named Christiaan who had started several companies there to create good jobs for people who previously worked in terrible conditions. He approached us about moving to Nepal to start a garment factory to employ survivors of exploitation or who are from marginalized backgrounds. It really resonated with our values and our belief that, as Christians, part of our identity is to help the poor.

We chose to go into the garment industry because we knew that many of the people who are survivors were vulnerable to exploitation in the first place because they weren’t educated and didn’t have good opportunities. The jobs we created had to allow people to jump in and learn the skills and thrive even if they couldn’t read or write.

Why did you choose Nepal as your base of operations?

Nepal is a mountainous Himalayan country, landlocked between China and India, and has developed a lot more slowly than its neighbors. There was a big civil war between 1996 and 2006. Now there’s a corrupt and unstable government that has driven most big business out of the country. That’s resulted in a 40 percent unemployment rate and more than 20 percent of the population living and working in other countries. Some find good jobs, but many get caught up in human trafficking. The jobs they end up in are essentially slave labor. Those that stay in Nepal can end up in underground jobs in which they are underpaid and under-protected.

In Nepal, exploitation is happening in many industries. But the garment industry often attracts those who are most vulnerable because they don’t need an education to learn how to sew, they don’t know their rights, and they don’t know how to appeal for fair treatment. Historically, in South Asia, the people from the lowest castes, who are at the bottom of society, are often the ones who do garment work.

One of your goals with Purnaa is to transform the garment factory from a place of exploitation to one of empowerment. How are you doing this?

Exploitation is the act of treating others unfairly in order to benefit from their work. We’ve seen many extreme cases of this in the garment industry.

At Purnaa, we don’t want that. We focus on skills development, including work skills and personal development. We intentionally rotate the work our employees do so they can learn different skills. We want them to have some versatility so they can have good jobs in the future. And on a weekly basis, we set aside time for trainings about things like hygiene, nutrition, and managing personal finances.

We’re committed to paying living wages. We assess this regularly, even month to month, so we know what it takes for a family—often with a single mom and kids—to live in a healthy way.

We want to create a place that encourages creativity. One of the ways we do that is by offering opportunities for our employees to learn about design. Outside of work hours they get to learn the fundamentals of design, taught by our in-house designer, who graduated from the Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising.

We also offer Nepali literacy classes and English classes because we want to empower people to succeed outside of Purnaa. That’s really fun. I see real growth in people. A woman who almost didn’t apply for a job because she couldn’t sign her name is now one of our best employees, and she’s reading and writing Nepali.

Empowerment comes with dignity. Creating a dignified workplace is about how you treat people and your attitude toward them. We have a real emphasis on not discriminating in the workplace, but also treating people—regardless of caste, gender, or religion—with the respect they deserve. People who come to Purnaa comment on what a positive work environment it is. That’s success, in my mind.

What, if anything, has improved in the global garment industry in recent years? What still needs to change?

We are seeing improvements. Consumers who want to buy things that are manufactured more ethically have access to more tools, like the Free2Work app or the Slavery Footprint website. There are now also certifications for brands like bluesign, Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS), and Worldwide Responsible Accredited Production (WRAP), which assess environmental sustainability and social responsibility. Through these, consumers can see which brands are complying with ethical standards for manufacturing.

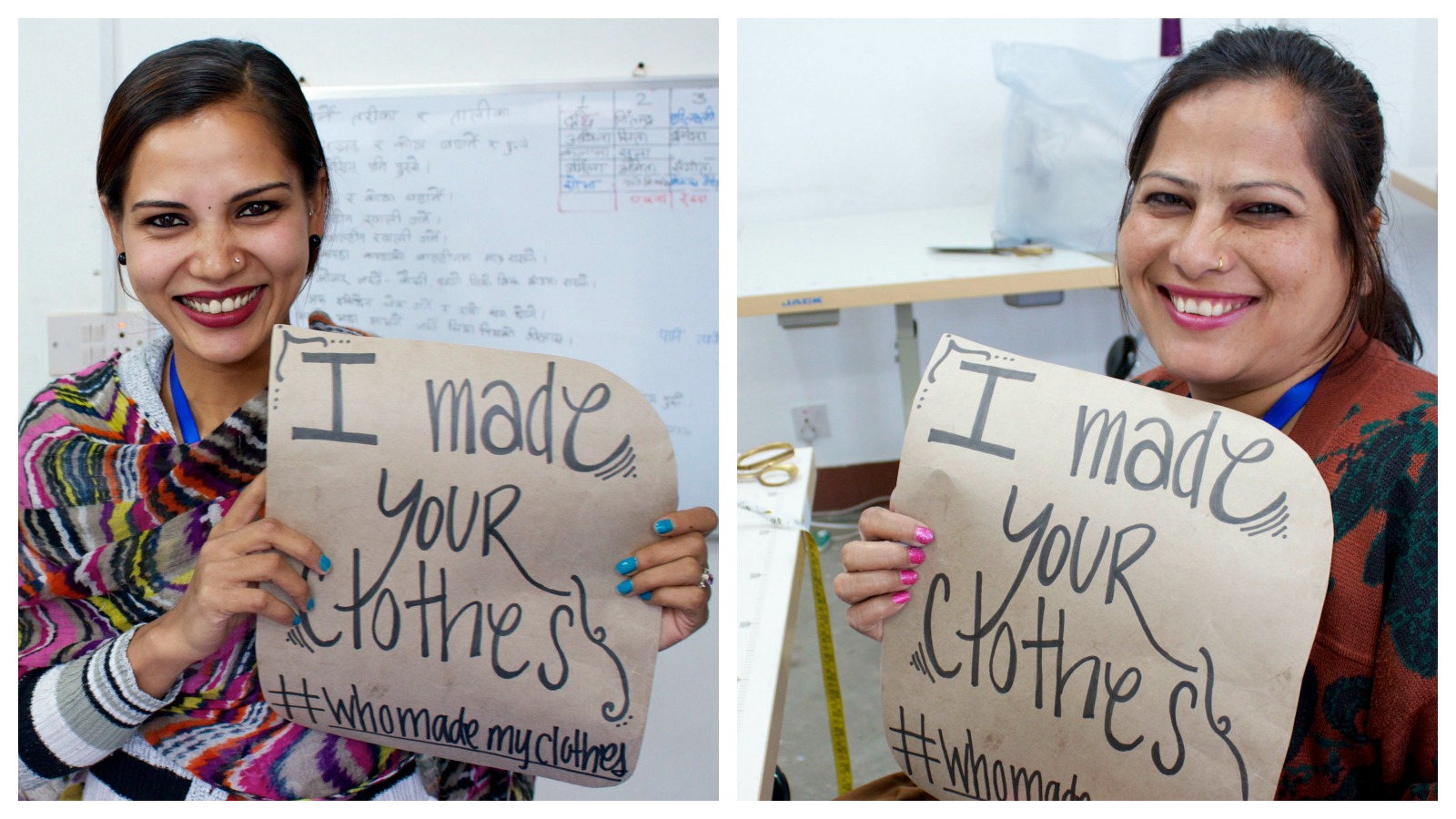

To me these are all indications that the industry is changing. There is a push for transparency, a push for consumers to be connected with who is making their clothes. As consumers are demanding ethical clothes, those brands are coming to Purnaa. They want clothes that are ethically sourced and workers who aren’t exploited. Change is happening.

But I don’t think we’ve solved it yet. We still need a simple way for consumers to know what is and isn’t a sustainable product. Brands need to believe that these systems actually give them a sales boost, that consumers will recognize these certifications and be more likely to buy their clothes.

We’re still in the early stages, but there’s definite growth and awareness. And after awareness comes the push for solutions, like the Fashion Revolution Day that’s happening today.

As you’ve delved into the business of running a garment factory, what has most surprised you?

I marvel at how much this country needs good jobs. As we hire people, we see they aren’t looking for charity or handouts. They want to work. They just need good opportunities to grow.

Some days at Purnaa, I’m so excited to see the transformation that happens. Aside from the skills they’re learning, other things click into place: “I can do this. I have value. I’m not the worthless person that I’ve been told all my life I am.” I’m surprised at how grateful people are to have the chance to make decent wages and improve their family’s quality of life.

What impact has moving to Nepal and starting Purnaa had on your family and your children?

That was something I worried the most about. You don’t ever want to do something in your life that will negatively affect your kids. But what’s been good has been seeing the heritage they have. I was driving with my kids and explaining to them what exploitation is. How many moms get to do this? I try to help them understand and participate in our purpose for why we’re here in Nepal.

Once, my seven-year-old son saw a lady who looked like she was dead lying by the side of the road. Along with his dad, he went to talk with her and got her help. She now lives in a group home for people with mental illness. My son goes and visits her and knows her and prays for her. That is something I really cherish as a mom: my son has opportunities to be compassionate. It would’ve been easy to ignore someone who needed help. As mothers, we have opportunities to help our children learn that it’s okay not to ignore people and that we can get involved.

One of my favorite verses is 1 John 3:16: “This is how we’ve come to understand and experience love: Christ sacrificed his life for us. This is why we ought to live sacrificially for our fellow believers, and not just be out for ourselves. If you see some brother or sister in need and have the means to do something about it but turn a cold shoulder and do nothing, what happens to God’s love? It disappears. And you made it disappear” (MSG).

God forbid that I ever stop the love of God from flowing in this world of need. This is what keeps me here on the hard days.