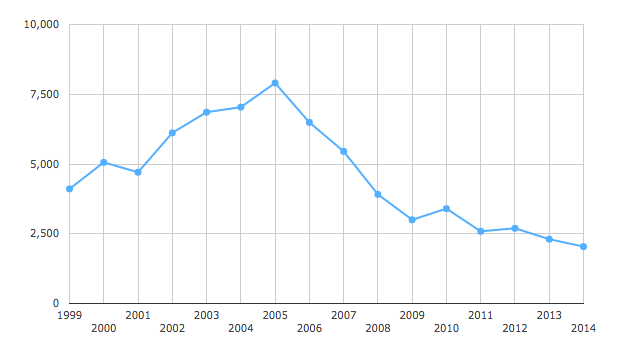

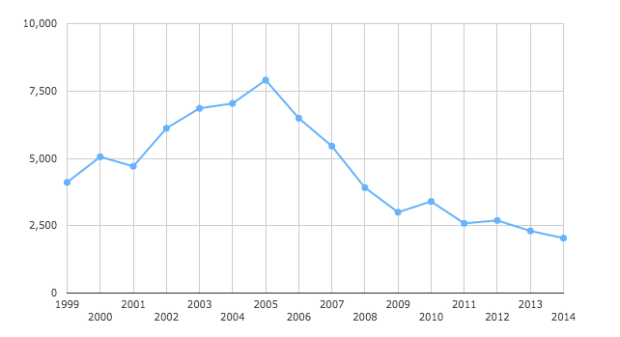

In 2004, Americans adopted 22,884 children from foreign countries—an all-time high.

Twelve years later, that number has dropped to 5,648 children—the lowest level in 35 years, according to recently released statistics from the US State Department on fiscal year 2015 (Oct. 1, 2014 to Sept. 30, 2015).

The sharp decline isn’t limited to the United States; global adoptions to the top 24 receiving countries dropped by 75 percent during the same 12 years.

Foreign adoptions have been in short supply while demand has surged among American evangelicals, prompted by Russell Moore and other leaders.

Last year, Americans adopted the most children from China, Ethiopia, South Korea, Ukraine, and Uganda. Most of these adoptive US parents lived in Texas, California, New York, Florida, and Georgia.

US State Department

US State Department

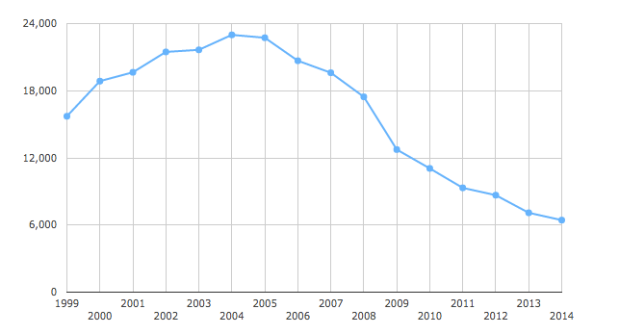

While reasons for the steady decline are multiple and complex, 80 percent of the drop in American adoptions can be traced back to three countries: China, Russia, and Guatemala, according to the State Department.

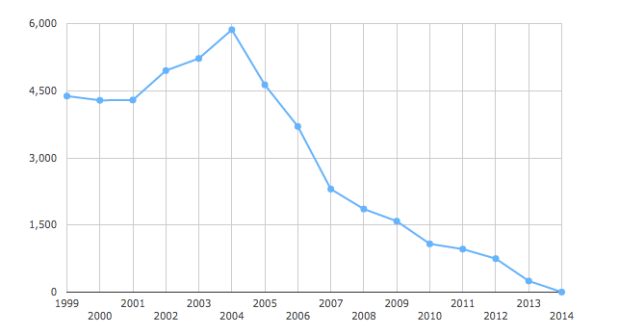

The Russian government banned Americans from adopting Russian children in 2012, leaving in limbo thousands of children and dropping the number of Russian adoptions from a high of 5,682 in 2004 to zero last year.

US State Department

US State Department

Guatemala suspended foreign adoptions to all countries while it works to clean up a system full of fraud and corruption. The 3,251 adoptions of Guatemalan children in 2004 dropped to 13 in 2015.

US State Department

US State Department

In the same vein, Uganda voted last month and the Democratic Republic of Congo moved in 2013 to make it harder for children to be adopted out of those countries in an attempt to close loopholes that enable child trafficking. (However, some advocates say the requirement that foreign adoptive parents stay one year in the country before their adoption is complete is “not realistic.”)

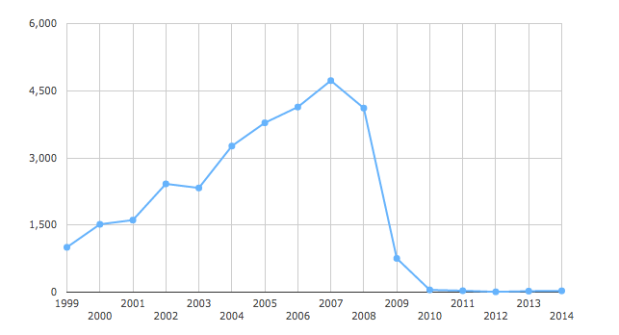

Foreign adoptions from China have dropped for an entirely different reason. In the past 10 years, “the Chinese government increased its efforts to promote the domestic adoption of children in need of a permanent home,” the State Department reported. “As a result, some 20,000 to 30,000 children are now placed domestically in China each year.”

US State Department

US State Department

Perhaps aided by the relaxation of China’s controversial one-child policy, Chinese children waiting for adoption are no longer primarily healthy baby girls (95% of adoptable children in 2005), but are now children that are traditionally harder to place: those who are older, part of sibling groups, or who have special needs. More than 90 percent of Chinese children waiting to be adopted today have special needs, according to the State Department.

That trend isn’t limited to China.

“Although not tracked by Federal data, strong anecdotal evidence and internal data from adoption agencies show that a far larger percentage of these children than ever before have special needs, are older than children adopted in the past, and/or are part of sibling groups,” wrote Jedd Medefind, president of the Christian Alliance for Orphans.

While it’s good that countries are working to safeguard children, “[i]t needs to be said unequivocally that constrictions in intercountry adoption bear tragic consequences for tens of thousands of children who today could be growing up in loving families were it not for these restrictions,” he wrote.

In fiscal year 2015, adoptions by Americans dropped the most from Ethiopia, Haiti, and Ukraine. The decline from these three counties alone outweighed the gain from other countries.

In Ethiopia—where CT examined a crackdown that curtailed adoptions by 90 percent—much work is being done to deinstitutionalize orphanages and reunify families. Adoptions to the United States dropped from 771 in 2014 to 335 in 2015.

In Haiti, where orphanages are overflowing but not with orphans, new government processes limited adoptions to 143 in 2015, down from 464 the previous fiscal year.

Ukraine’s 40 percent drop in out-of-country adoptions is partially because the eastern part of the country—where many adopted children come from—is currently held by pro-Russian separatists, the State Department said. (Russia has also blocked adoptions from Crimea.) Ukraine also saw a 60 percent rise in domestic adoptions from 2006 to 2013, Ruslan Maliuta, international facilitator of World Without Orphans, told CT.

“I don’t expect international adoptions will ever be over 20,000 again, for a lot of reasons,” Mike Douris, president of Orphan Outreach, told CT. “They’ll always be a part of orphan care, but not the major thrust. I think domestic adoption and foster care in these countries is going to emerge and be a big growth over the foreseeable future.”

Despite its proximity, Mexico is still in the top five countries that take the longest to process adoptions. The average number of days it takes to complete an adoption across the southern border dropped from 741 in 2012 to 692 in 2015. The only countries that take longer are Georgia (766 days), the Dominican Republic (807 days), Belize (812 days), and Mongolia (1,067 days).

Albania is the most expensive country to adopt from: the median adoption fees are more than $30,000. Romania ($25,355), Dominican Republic ($25,300), Armenia ($24,375), and Lithuania ($22,135) round out the top five. The least expensive countries to adopt from are Ireland ($250), the Netherlands ($4,500), and Serbia ($5,000).

Less than 100 American children (93) were adopted into foreign countries in 2015. Most went to Canada (39) and the Netherlands (37), and most came from Florida (65), followed by New Jersey (12), New York (4), and California (4).

The states that adopted the most children last year were Texas (392), California (391), New York (269), Florida (250), and Georgia (240). The states that adopted the fewest children: Rhode Island (8) and Delaware (9).

CT’s past reporting on adoption and orphans includes how adoption has surged in popularity among evangelicals, how the high-profile Haiti adoption scandal might impact such efforts, and debate over the ethics of international adoption.

CT has also noted the trend toward open adoptions, how adoption horror stories are not the whole story, and three views on how churches can best support parents who adopt from overseas.

[Image courtesy of John Manuel Sommerfeld – Flickr]