When it comes to domestic violence, Protestant pastors want to be helpful but often don’t know where to start.

Most say their church would be a safe haven for victims of domestic violence.

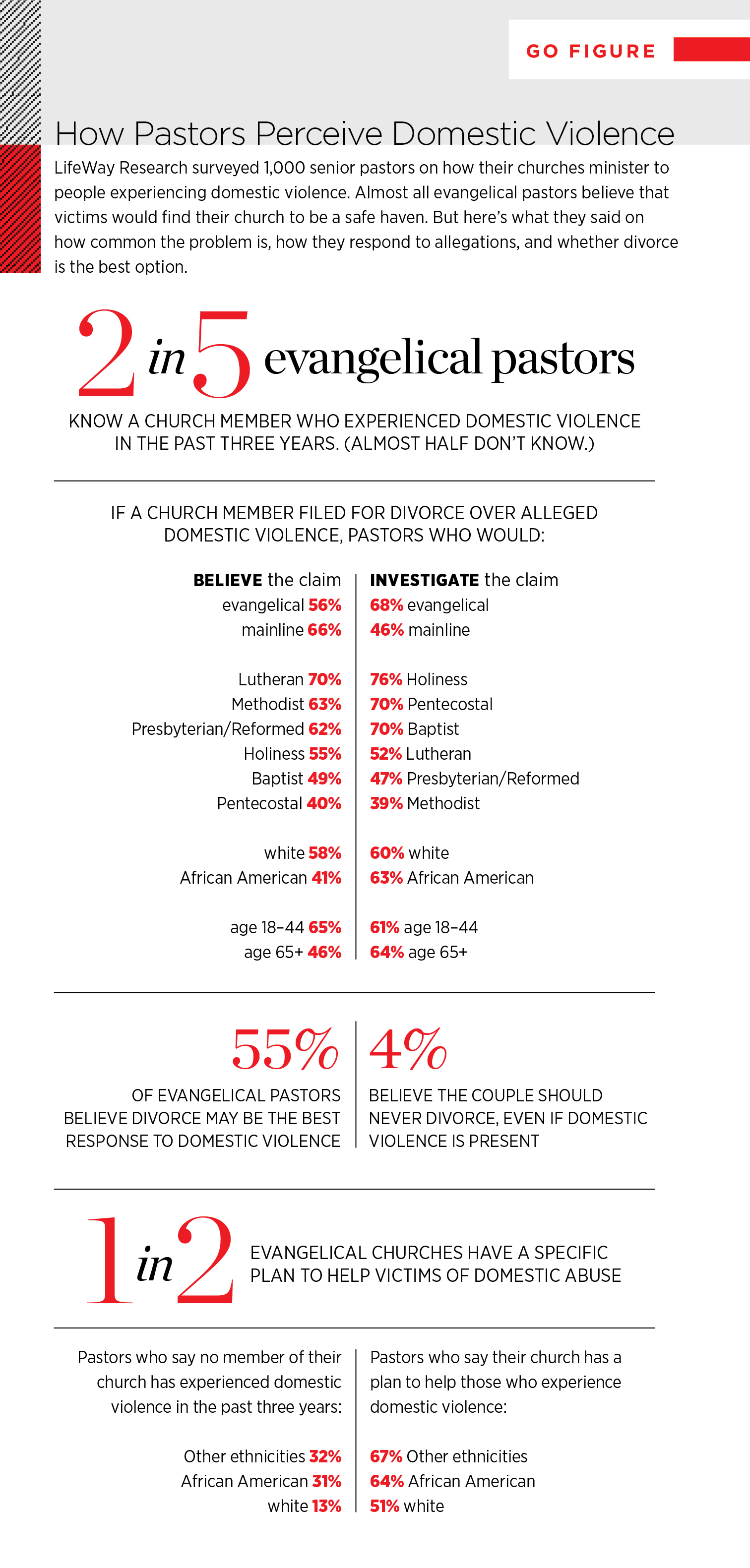

But many don’t know if anyone in their church has been a victim of domestic violence. And only half say they have a plan in place to help if a victim comes forward.

Those are among the findings of a new report on churches and domestic abuse from LifeWay Research, based on a phone survey of 1,000 Protestant senior pastors.

The study was sponsored by Autumn Miles, a radio host and speaker whose church was caught off guard when she told them about her domestic violence experience.

“If a woman comes forward and says, ‘I need help—I am being abused,’ a church needs to respond,” she said. “There’s a lot to lose if churches get this wrong.”

Most pastors (87%) already believe that “a person experiencing domestic violence would find our church to be a safe haven.” Eleven percent somewhat agree. One percent are not sure.

And most pastors (89%) also believe their church regularly communicates that domestic violence is not okay.

Yet almost half of pastors say they don’t know if anyone in their church has been a victim of domestic violence in the last three years (47%). A third say a church member has been a victim of domestic violence (37%). Fifteen percent say no one has experienced domestic violence.

Church size plays a role in whether pastors know of a domestic violence victim. Pastors at bigger churches—those with more than 250 attendees—are most likely (65%) to know of a victim of domestic violence in their church. Pastors at smaller churches—those with fewer than 50 attendees—are least likely to know of a victim (20%).

Pastors in the West (45%) and Midwest (42%) are more likely to know of a victim than those in the South (33%).

Scott McConnell, executive director of Lifeway Research, said churches want to help victims of domestic violence but aren’t always effective at doing so.

McConnell said he suspects there are more victims of domestic violence in churches than pastors realize. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, almost a quarter of American women (24.3%) and 1 in 7 men (13.8%) have “experienced severe physical violence by an intimate partner.” Given those numbers, there are likely victims of violence even in a small church, McConnell said.

“Statistics on sinful activities consistently show that church attendees act better [than non-attendees] but are not without sin,” he said. “It is naïve to assume a church could remain immune to domestic violence.”

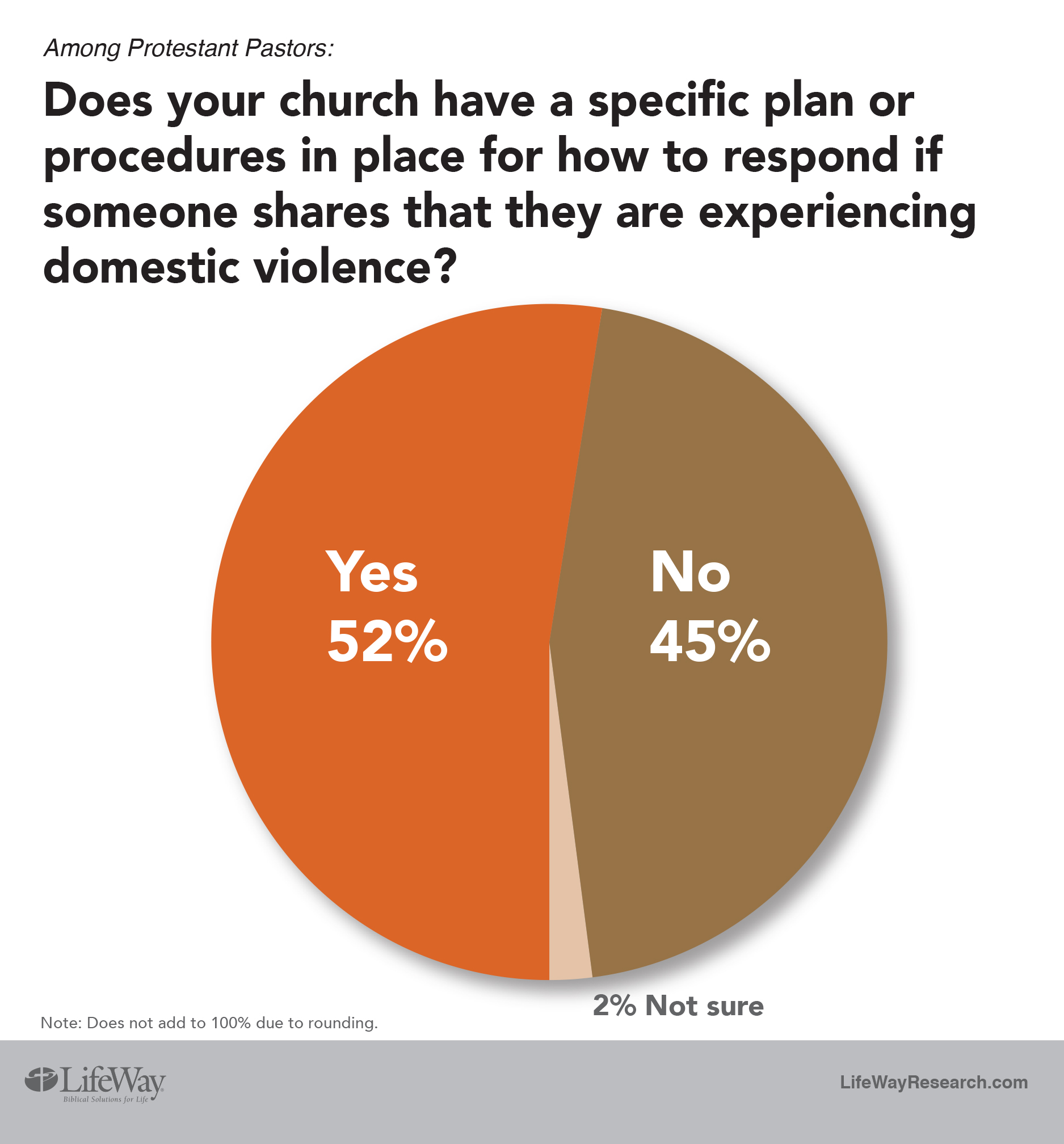

This lack of experience or awareness might explain why many churches don’t have a plan to assist victims of domestic violence, McConnell said.

Only about half of churches (52%) have a plan to assist victims of domestic abuse. Forty-five percent have no plan. Two percent of pastors aren’t aware of a plan.

Most churches with 250 or more people have a plan (73%). So do many Methodist (63%) and Pentecostal (66%) churches. Fewer Baptist (52%), Presbyterian/Reformed (45%), Holiness (45%), Lutheran (44%), or Church of Christ (41%) churches have one.

Among the resources churches offer to victims:

- Three-quarters have a referral list for professional counselors (76%).

- Two-thirds have finances to assist victims (64%).

- Sixty-one percent can provide victims a safe place to stay.

- About half have a referral list for legal help (53%).

- Half have someone in the church who has experienced domestic violence victims can talk to (49%).

Churches also offer other assistance like referrals to shelters or state agencies, pastoral care, and support groups.

The kind of help offered to domestic violence victims can vary by denomination.

Baptists (66%) and churches with more than 250 attendees (68%) are more likely to offer victims a safe place to stay. Lutherans (55%) and Methodists (54%), as well as churches with fewer than 50 attendees (55%), are less likely.

Baptist (71%), Presbyterian/Reformed (67%), and Church of Christ (67%) churches are more likely to have financial resources to help victims of domestic violence than Methodist (53%) or Lutheran (49%) churches.

Bigger churches are most likely to be able to connect a victim with someone who has experienced abuse (65%). Pentecostals (61%) are more likely than Presbyterian/Reformed (43%), Methodist (42%), and Lutheran (35%) pastors to do the same.

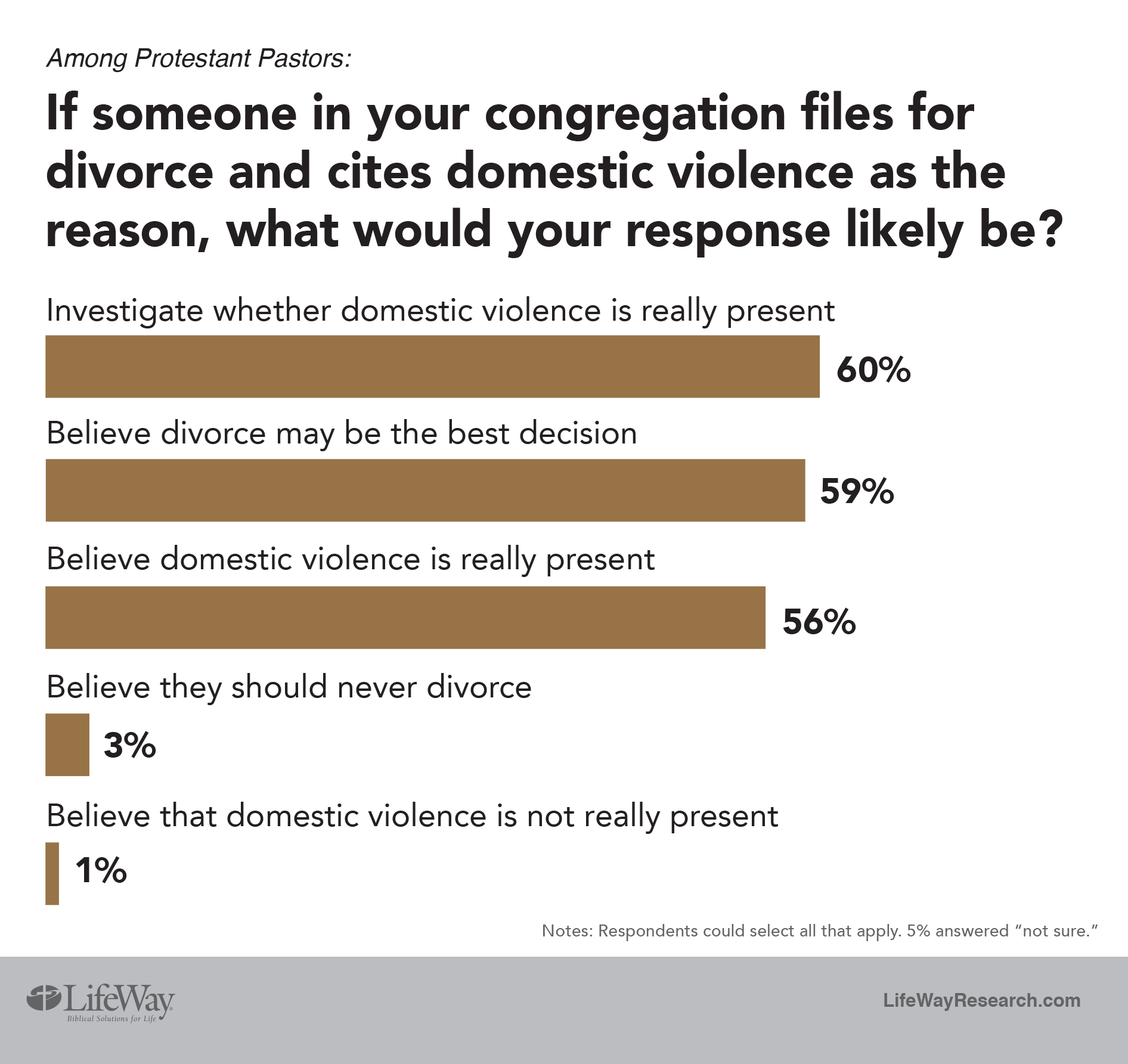

The issue of divorce is one roadblock for churches that want to help victims of domestic abuse.

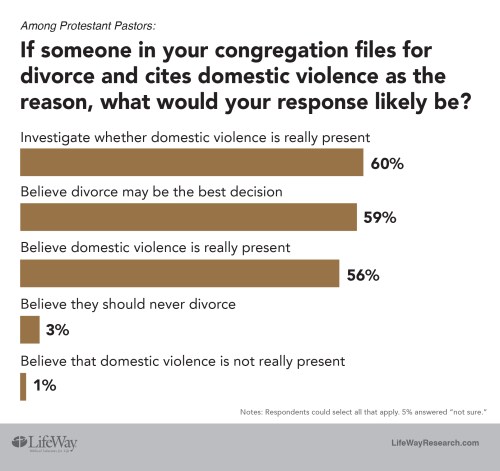

If a church member files for divorce and cites domestic violence as a cause, pastors often respond with skepticism. Three out of five say they’d investigate the claims (60%), even though more than half say they would believe the charges (56%). About the same number would say divorce was the best option (59%).

The study showed 43 percent of pastors are unwilling to say whether or not they would believe abuse took place.

Lutheran (70%), Methodist (63%), and Presbyterian/Reformed pastors (62%) are most likely to believe domestic violence took place if a church member files for divorce and cites domestic violence as a cause. Baptist (49%) and Pentecostal (40%) pastors are less likely.

Baptist (70%), Pentecostal (70%), and Holiness (76%) pastors are more likely to investigate claims of domestic violence. Lutherans (52%), Presbyterian/Reformed (47%), and Methodists (39%) are less likely.

A 2014 LifeWay study found domestic violence is rarely discussed in Protestant church settings. In that study, 4 in 10 pastors said they rarely or never addressed the issue. Another 22 percent discuss the issue once a year.

Julie Owens, a North Carolina-based consultant who has designed domestic violence prevention programs for churches and the Department of Justice, said churches want to be safe havens for victims. But there’s no way for a victim to know a church is a safe place if the pastor never discusses the issues.

Church leaders had a hard time believing Autumn Miles’s claims were true—in part because they didn’t think domestic violence could happen in the church.

Launching investigations into cases like Miles’s can do more harm than good, Owens said. If a pastor talks to an alleged abuser, the abuser will often deny the claims and then retaliate against the victim, she said.

And abusers often know how to manipulate pastors, she said. Abusers will ask for forgiveness and say they want to reconcile with their spouses—and that’s what pastors want to hear, she said.

“It can be a lot easier to believe the abuser than to help a victim,” she said.

Ensuring a victim’s safety has to come first, she said. That often means connecting victims to outside resources like counselors, shelters, and law enforcement. Pastors and churches, she said, aren’t always equipped to deal with the complicated needs of domestic violence victims.

“Churches underestimate the spiritual, psychological, and emotional damage done by domestic abuse,” she said.

Ignoring the issue in public settings can undermine a church’s efforts to help domestic violence victims, said McConnell.

“You can have great resources in place to help victims—but if no one knows they exist, those resources won’t do any good,” he said.

Methodology: The study was sponsored by Autumn Miles. The phone survey of Protestant pastors was conducted August 22–Sept. 16, 2016. The calling list was a stratified random sample, drawn from a list of all Protestant churches. Quotas were used for church size. Each interview was conducted with the senior pastor, minister or priest of the church called. Responses were weighted by region to more accurately reflect the population. The completed sample is 1,000 surveys. The sample provides 95 percent confidence that the sampling error does not exceed plus or minus 3.2 percent. Margins of error are higher in sub-groups.