In this series

[Update: On April 20, Russia’s high court banned Jehovah’s Witnesses as extremists.]

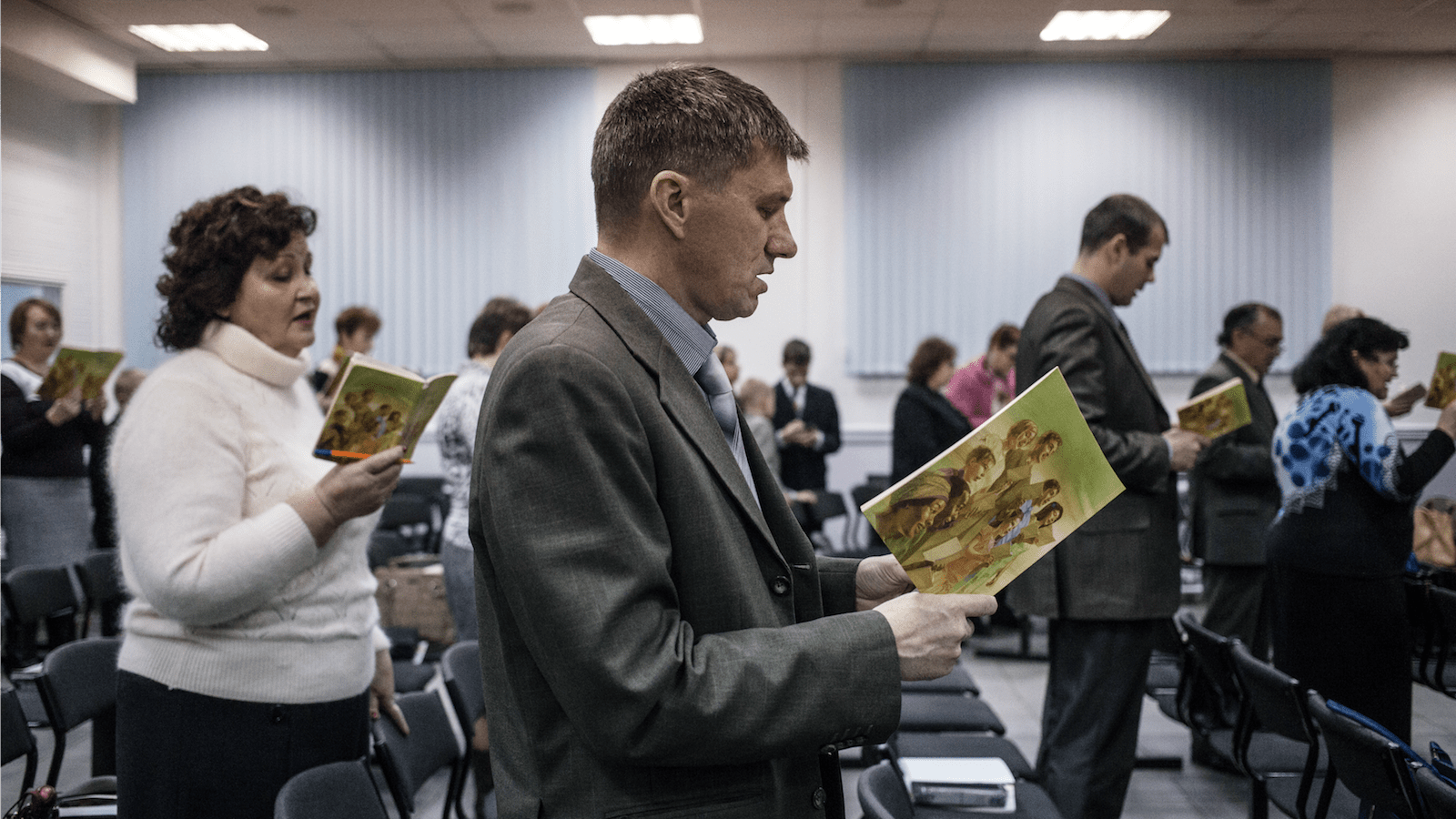

Jehovah’s Witnesses have never held much clout in Russia, where the Orthodox Church dominates both the religious and political landscape. But a government lawsuit now threatens any future for their faith in public life.

The door-to-door evangelists have historically served as a bellwether for religious freedom for other minority groups. In Russia, that includes evangelicals, who remain ambivalent over whether to defend the rights of Witnesses as a fellow non-Orthodox faith.

Last week, the Justice Ministry submitted a Supreme Court case to label the Jehovah’s Witnesses headquarters an extremist group. This would allow Russia to enact a countrywide ban on its activity, dissolving its organization and criminalizing its worship. The court will convene to rule on the case in April.

“Considering that the religion of the Jehovah’s Witnesses is professed by hundreds of thousands of Russian citizens, [liquidation] would be a disaster for rights and freedoms in our country,” said Yaroslav Sivulsky, a representative of the targeted Jehovah’s Witnesses headquarters, to Forum 18. The ban would impact about 175,000 followers in 2,000 congregations nationwide. “Without any exaggeration, it would put us back to the dark days of persecution for faith.”

Though both groups have been restricted and punished by Russia’s recent anti-missionary law, evangelicals can’t necessarily expect the same treatment.

“No one else is in a comparable position to that of the Jehovah’s Witness community,” Alexander Verkhovsky of the SOVA Center for Information and Analysis told Forum 18 last month.

Russian Protestants don’t consider themselves as extreme—or as annoying—as the Witnesses, and they aren’t too eager to speak out against the recent case against them.

“Baptists and Lutherans are often regarded as traditional religions by Russian judicial practice and by the Orthodox,” said William Yoder, spokesman for the Russia Evangelical Alliance. “Protestants do at times succumb to the temptation to accept the common Russian division between ‘traditional’ and ‘non-traditional’ religions if they themselves happen to be on the right side of the divide.”

The warnings against Jehovah’s Witnesses have stacked up over the past decade in particular, with dozens of regional charges of extremism and more than 80 of its books, pamphlets, and other texts (including its magazine, The Watchtower) banned in Russia, according to The Moscow Times.

Last Tuesday’s suit comes a year after the government launched an investigation against the national headquarters in St. Petersburg. Police raided an average of three Jehovah’s Witnesses centers a month in 2016, Forum 18 reported. In areas where the group has already been banned, police cite their criticism of traditional Christianity and Orthodoxy—as well as their objection to military service—as grounds for the extremist label.

In the United States, 24 percent of Jehovah’s Witnesses identify as “born-again” and 17 percent as “evangelical.” Yet evangelicals have significant theological reasons to oppose them. As The Gospel Coalition noted, Jehovah’s Witnesses do not ascribe to the Trinity, do not believe that Jesus is divine, and avoid traditional markers of Christianity including Christmas, Easter, and the cross.

In Russia, they don’t participate in interfaith efforts among minority groups. Plus, they are promoting a competitive theology in a way many evangelicals disagree with. “Protestants consider the evangelistic activities of Jehovah’s Witnesses to be excessively intrusive and aggressive,” said Michael Cherenkov, the Ukraine-based executive field director for Mission Eurasia.

While Jehovah’s Witnesses push their distinct teachings on God and the end times, evangelicals contextualize their sermons to build on Russian familiarity with Christian history and Orthodox culture. Because of their theological and methodological differences, “Jehovah’s Witnesses in Russia appear to be foreign and almost alien,” Cherenkov said.

Those two characterizations are especially damning in Russia, where leaders are wary of outsider influence. Before the “missionary activity” restrictions from last year’s legislation, the country adopted a “foreign agent” law to regulate all international groups, NGOs, and foreign missionaries with more oversight and paperwork.

A similar dilemma emerged in Russia in 2004, when CT reported how Jehovah’s Witnesses were banned from Moscow under the application of a 1997 religion law. Back then, religious freedom advocates warned that “many of the claims made about the Jehovah's Witnesses practices could also be made of other religious communities practices as well.”

Traditional Russian Orthodoxy continues to be increasingly conflated with a sense of Russian patriotism and nationalism, so many believe the government will keep pushing against the freedoms of minority faiths.

“A ban on Jehovah’s Witnesses is just the beginning in a series of repressions. Society needs an internal enemy to which the government can point in full cooperation with the Russian Orthodox Church,” Cherenkov said. “The silence of Protestants with regard to repressions against Jehovah’s Witnesses will merely unleash a new wave of restrictions and repressions.”

Jehovah’s Witnesses have been on the front line of religious liberty in the US as well. As chronicled in the 2006 documentary Knocking, covered by CT:

Witnesses were in the Supreme Court 45 times between 1935 and 1958 fighting for their rights of freedom of religion, freedom of expression, and patients’ rights. Long before the founding of Christian public interest law firms, such as the Liberty Fund, The Becket Fund, and the ACLJ [American Center for Law and Justice], the Jehovah's Witnesses were using the courts to establish liberties.

CT has previously reported on efforts to overturn Russia’s 2016 anti-evangelism law, what Russian evangelicals think of Donald Trump, and Putin’s popularity among them.