To remain the world’s largest religious group, Christians are going to have to heed Genesis and be fruitful and multiply—not just in the mission field, but also in the bedroom.

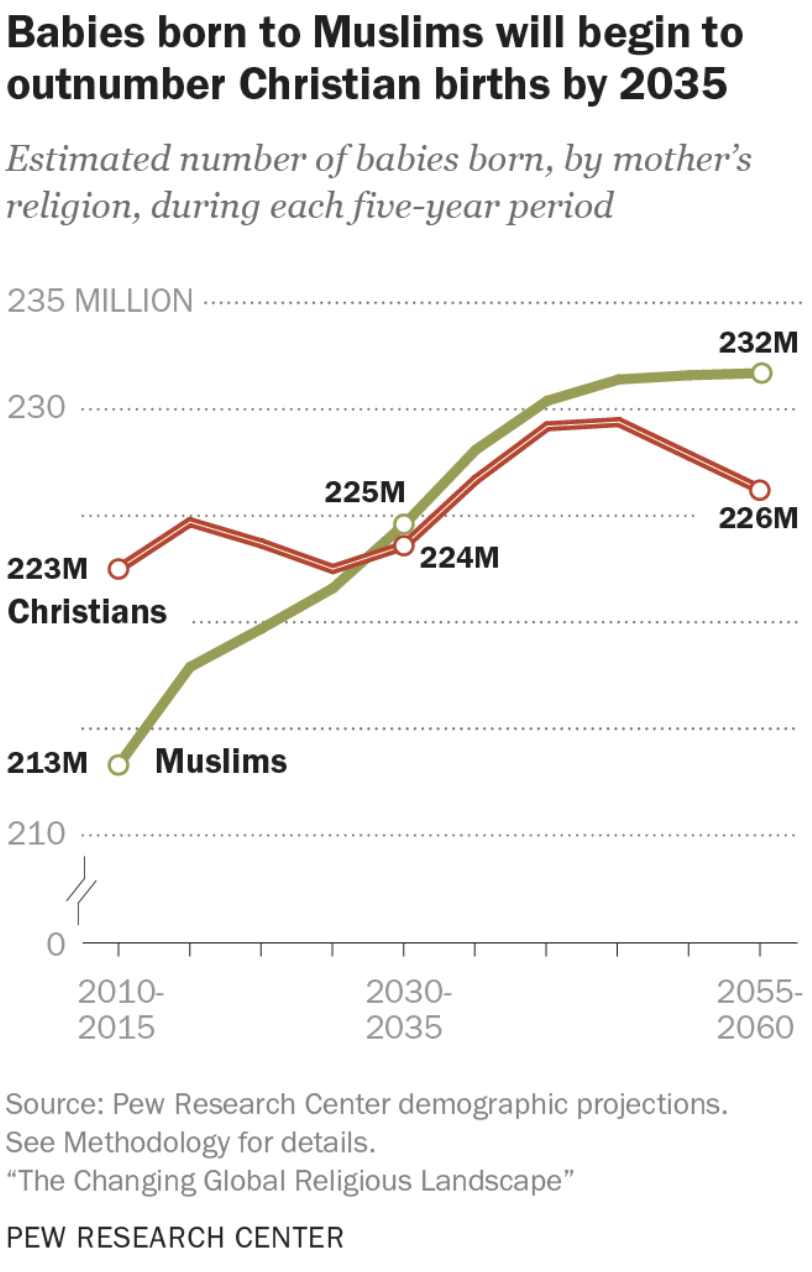

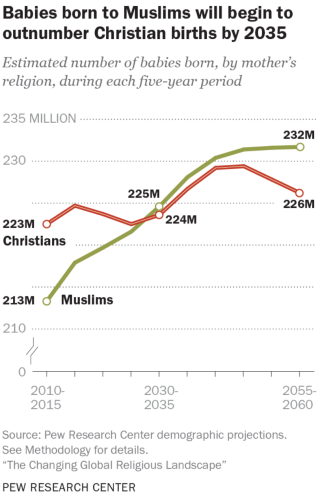

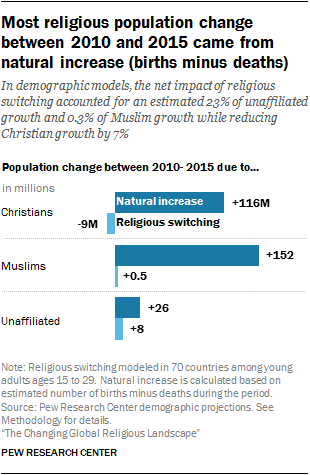

Christian births will be outpaced by Muslim births within 20 years, according to new projections released today by the Pew Research Center. Between 2030 and 2035, Christian mothers are expected to welcome fewer babies (224 million) than Muslims (225 million) for the first time in history.

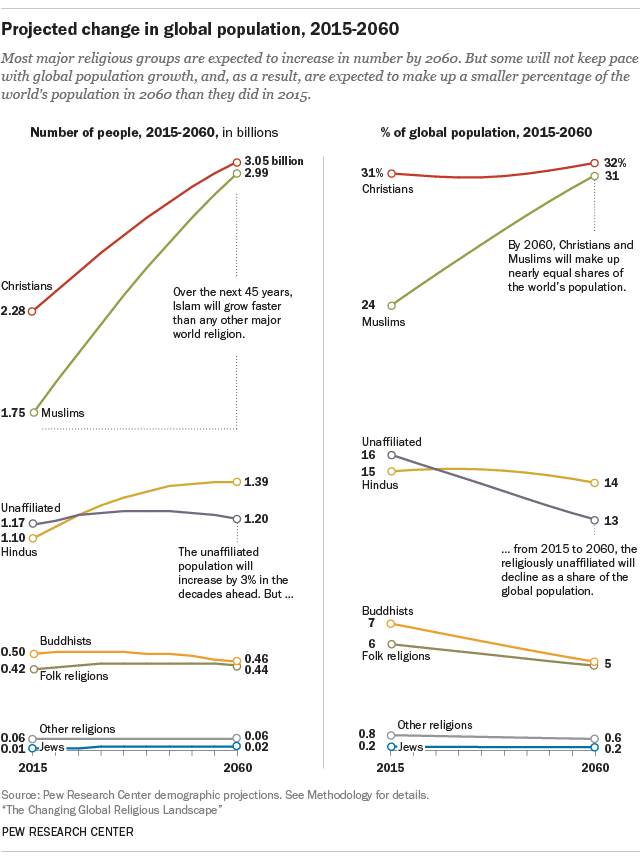

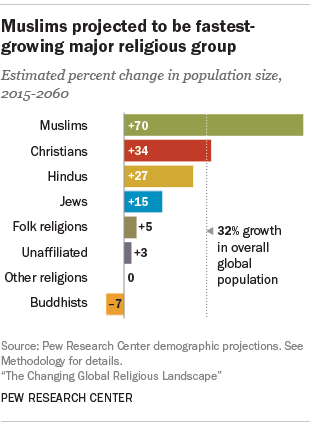

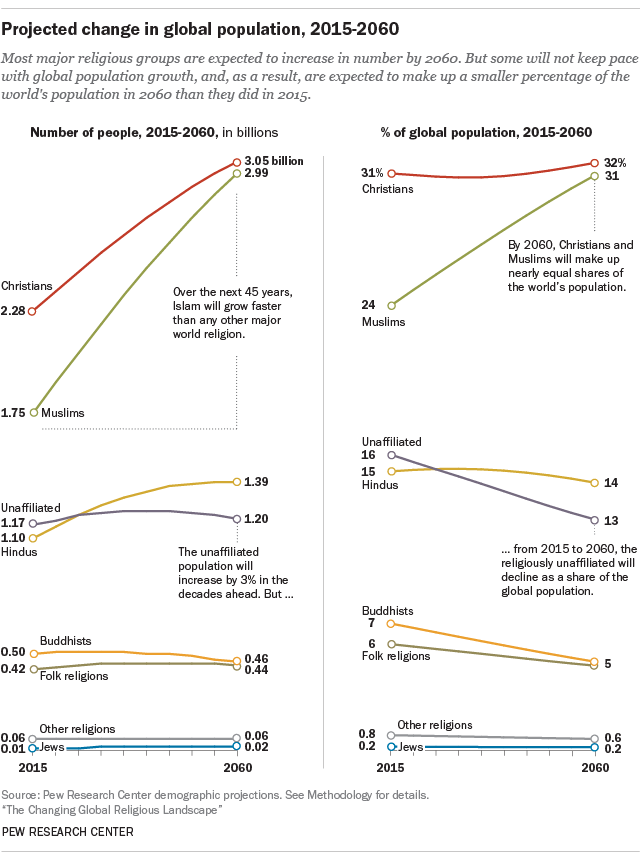

By 2060, such growth will result in the global population of Christians and Muslims approaching parity—totaling 3.1 billion and 3 billion, respectively—with each tradition accounting for nearly 1 in 3 people on earth. Over the 45-year period, the Christian population is predicted to hold steady at 31 percent, while the Muslim population is predicted to rise from 24 percent today to the same level.

The new report extends Pew’s respected prediction of how Christianity and Islam will change by 2050. It also adds more detail about the expected impact of conversions, which don’t change the size of religious populations as dramatically as birth rates. (CT previously examined how babies will halt the Great Commission.)

“In different areas, you’ll see different factors, but a lot of the growth is through birth,” said Bert Hickman, senior research associate at the Center for the Study of Global Christianity (CSGC) at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary.

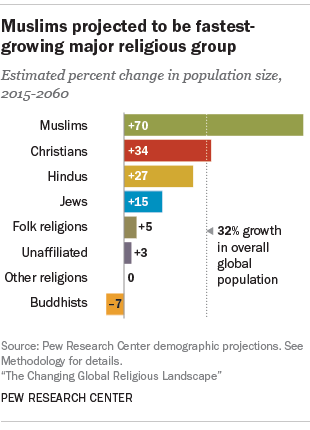

Currently, Muslim families are having more kids than any other religious group in the world, according to the Pew findings. Muslims around the world average 2.9 children; Christians come in second with 2.6. No other faith has birth rates high enough to grow faster than the population overall. Women without a religious affiliation have just 1.6 kids on average, and the “nones” are expected to shrink from 16 percent of the global population in 2015 to 13 percent in 2060 as a result.

The findings come as no surprise to experts. Those who study religious demographics have seen the statistics pointing to Christian and Muslims—not Christians and secularists—as the two groups contesting most for numbers in the decades to come.

But the projections do come as a surprise to some Americans, particularly the millennials who expected the world would get less religious and not more religious as they grew up.

About half of Americans correctly believe that Christianity is currently the largest faith in the world, while a quarter say Islam. A significant portion of religious nones (44%) and people under 30 (46%) believe that the religiously unaffiliated are bound to become the largest religious group in the world by 2050, Pew found. A little less than a third of Christians agreed.

Eric Kaufmann, author of the 2011 book Shall the Religious Inherit the Earth?, confidently answered the question in the affirmative; there’s simply not enough population growth among atheists and the non-affiliated to compete with the Muslim and Christian baby booms. By 2055 to 2060—as far out as the forecast goes—fewer than 1 in 10 babies born on the planet will be to religiously unaffiliated moms. Meanwhile, 7 in 10 will be either to Muslim or Christian moms.

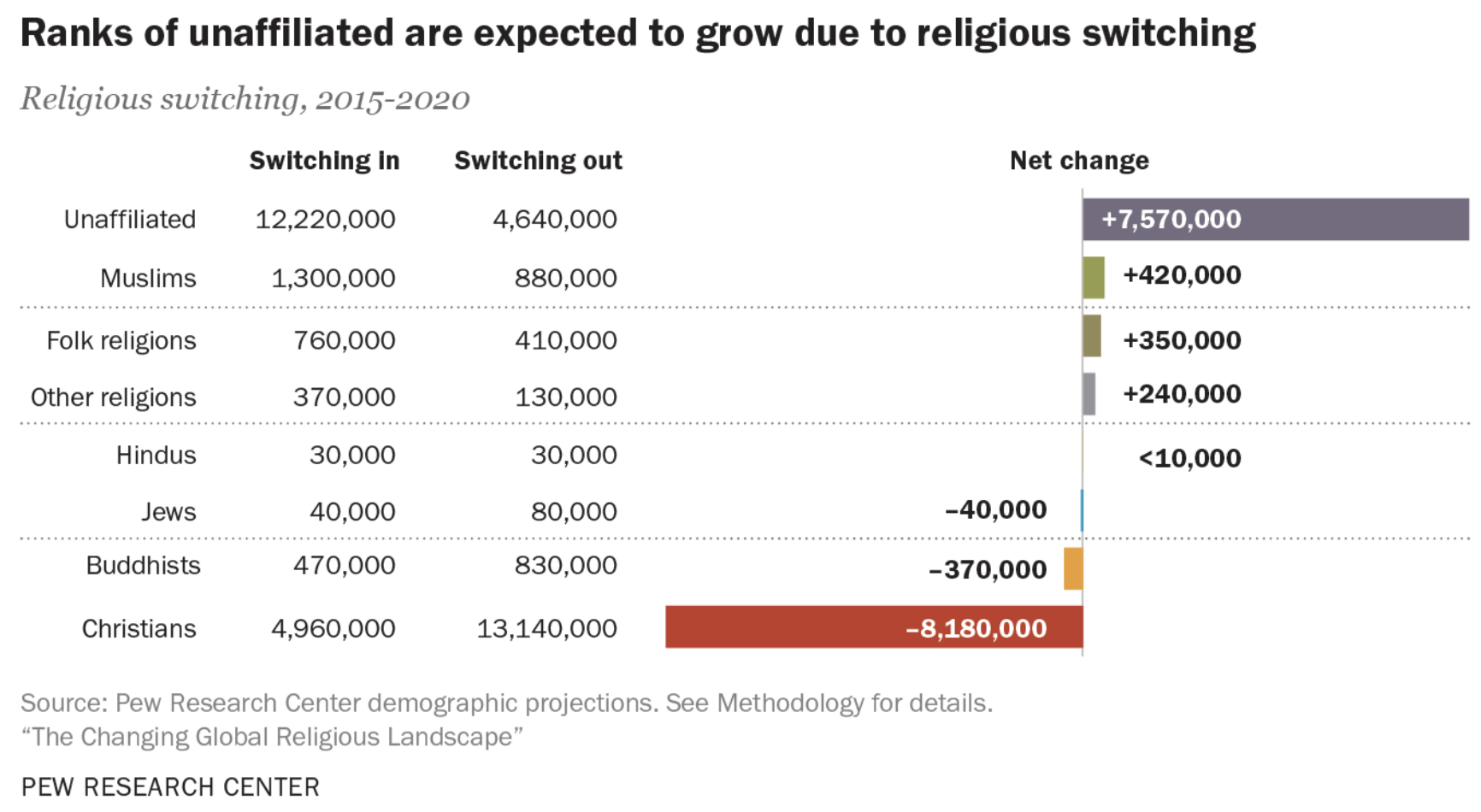

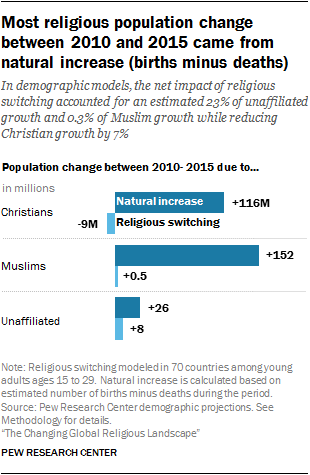

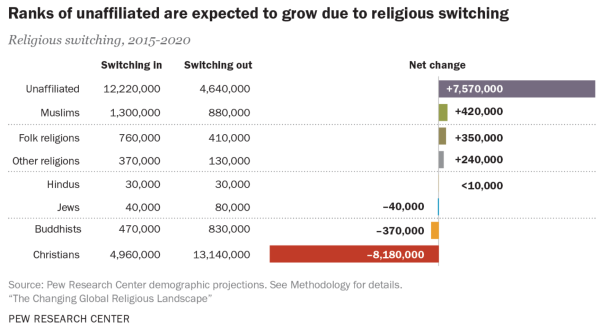

Particularly in North America and Europe, Christians are correct when they notice people leaving their pews. Over the next few years, evangelism on a global scale is expected to result in a net loss for the church. About 5 million will convert to Christianity between 2015 and 2020, while 13 million will leave the faith, according to the Pew projections. That’s a bigger loss due to conversions than any other religious group. Most will become “nones.”

Here’s how the researchers describe conversion trends, which can be tricky to predict:

At present, the best available data indicate that the worldwide impact of religious switching alone, absent any other factors, would be a relatively small increase in the number of Muslims, a substantial increase in the number of unaffiliated people, and a substantial decrease in the number of Christians in coming decades. Globally, however, the effects of religious switching are overshadowed by the impact of differences in fertility and mortality.

Hickman doesn’t believe such trends should discourage evangelism. Churches regularly celebrate conversions from nominal Christians that wouldn’t count as switches in the broader global data. And it’s hard to use statistics as a reason for retreat: Missions groups already have to balance the healthy tension of wanting to prioritize places without any gospel presence and investing in areas where the Holy Spirit is actively drawing conversions.

“The gospel is for everyone. It’s not just a numbers game,” he said. “Do not look at them as numbers. They represent people.”

The CSGC calculates the Christian population to be a couple percentage points higher than Pew (33.4% in 2015, and 36% in 2050), partly due to differences in tracking conversions in certain areas like communist China, where much mission activity takes place underground.

Pew cites estimates that more than half of the population in China, the world’s most populous country, is unaffiliated, and just 5 percent is Christian. Its projections do not include possible Christian conversions, but researchers said, “If Christianity expands in China in the decades to come—as some experts predict—then by 2060, the global numbers of Christians may be higher than projected, and the decline in the percentage of the world’s population that is religiously unaffiliated may be even sharper than projected.”

The CSGC does predict that the percentage of unevangelized people in the world will stay constant, from 28.4 percent in 2017 to 28.2 percent in 2050.

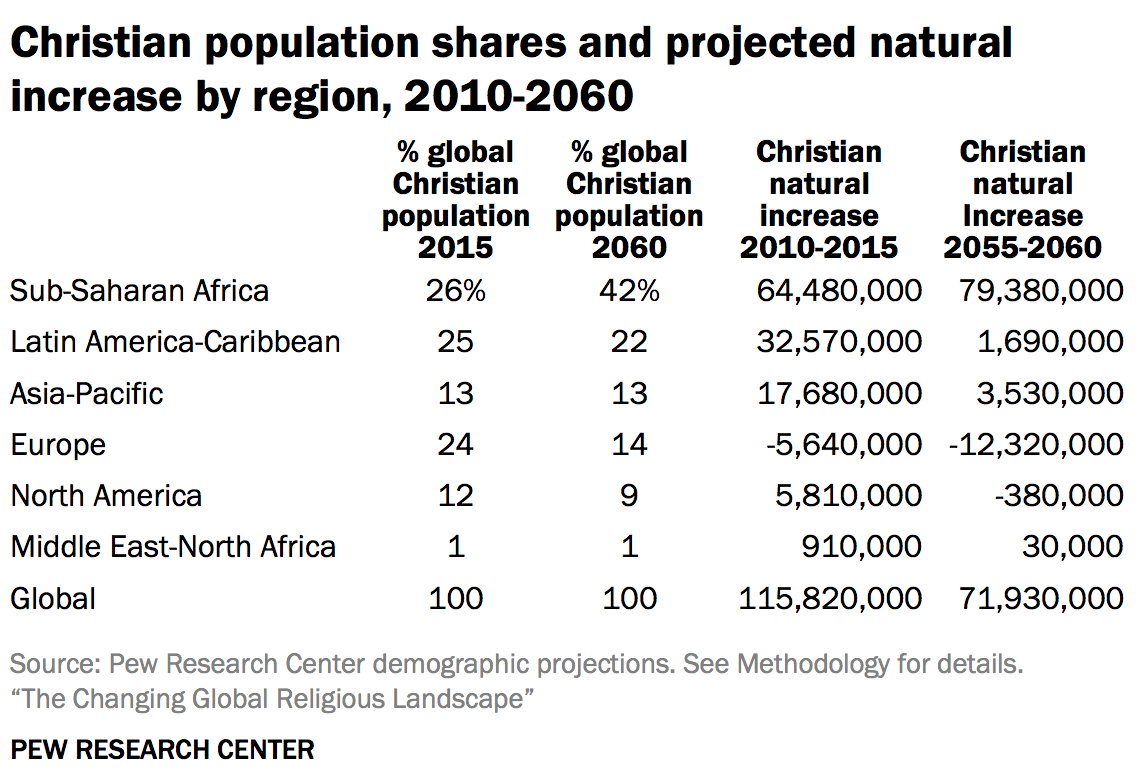

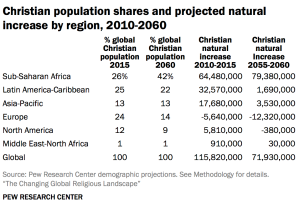

An area where Christianity is sure to surge is sub-Saharan Africa. The region will be home to 42 percent of believers in the world by 2060, up from 26 percent in 2015, due to high fertility rates. The Lausanne Movement identified the coming decades as a crucial period for mission in Africa, noting that the African population will double by 2050 and the youth population will reach a peak of 663 million.

“For the next 35 years there is the opportunity to reach the greatest ever number of African youth with the love of Christ. This great strategic opportunity can easily be missed,” according to Lausanne’s 2015 global analysis report.

The most crucial country will be Nigeria, the continent’s most populous and currently evenly split between Christians and Muslims. CT previously reported how one major Nigerian church is trying to have as many babies as possible.

But what about areas where fertility rates are declining? If births really are a more effective way to grow a population, can Christians attempt to boost the church’s birth rate to secure a stronger future for the faith?

For years, watching North American couples delay marriage and birth rates drop, evangelicals have debated just how fruitful God asks that they be. Hickman points out that immigration is a factor that has bolstered the North American church—foreign-born Christians keep up the region’s Christian population and often have more children. Pew calculates that the United States gains 600,000 new Christians each year thanks to immigration.

CT previously reported the best prediction of how Christianity and Islam will change by 2050, as well as how birth rates block the Great Commission (though Nigerian Christians aim to outbirth Muslims).