Most evangelicals don’t consider themselves single-issue voters, and new data suggests racial justice may play a big role in political conversations among believers.

According to a LifeWay Research survey, a majority of evangelicals by belief are committed to pro-life values and racial justice. Both issues can be political dealbreakers.

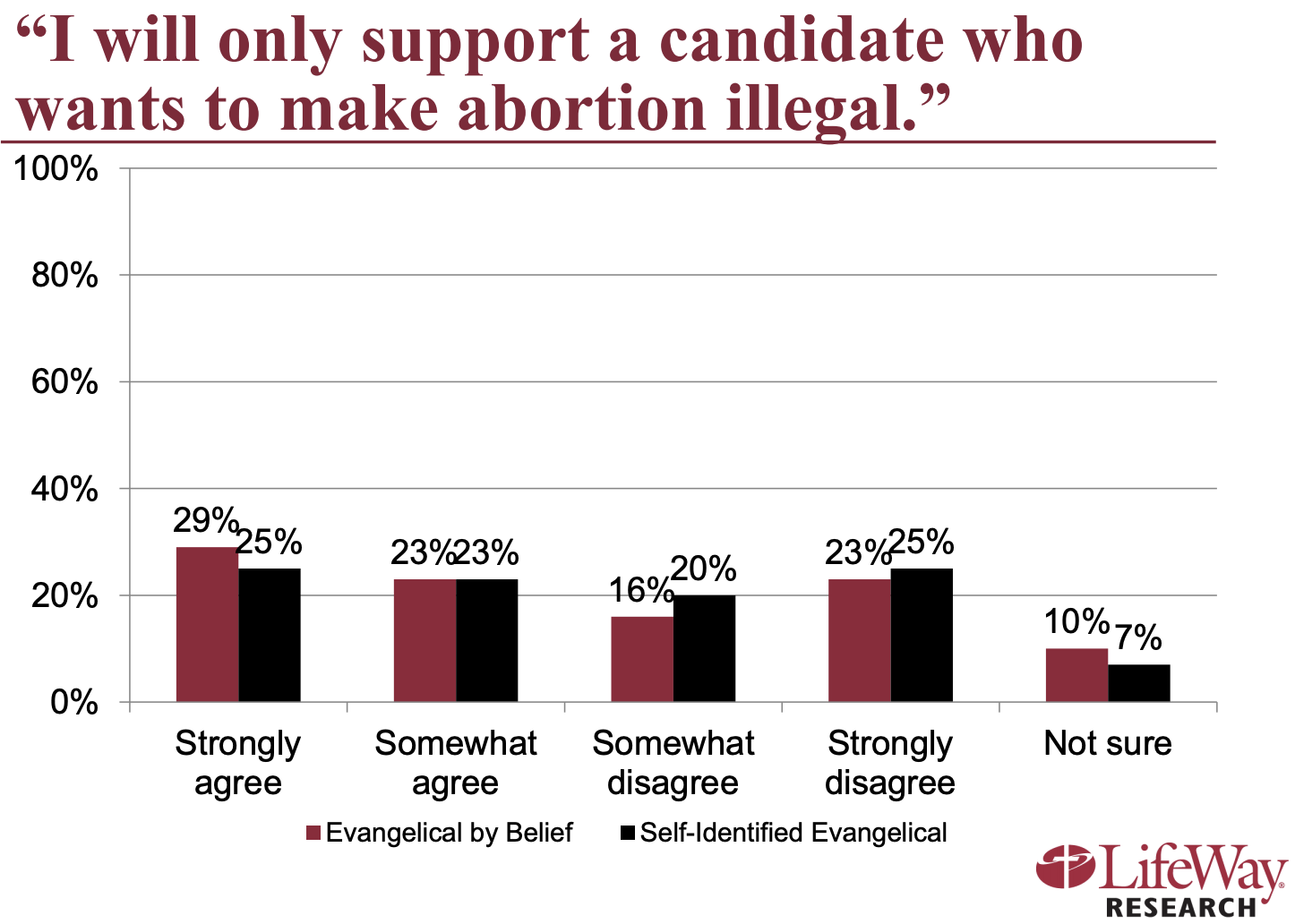

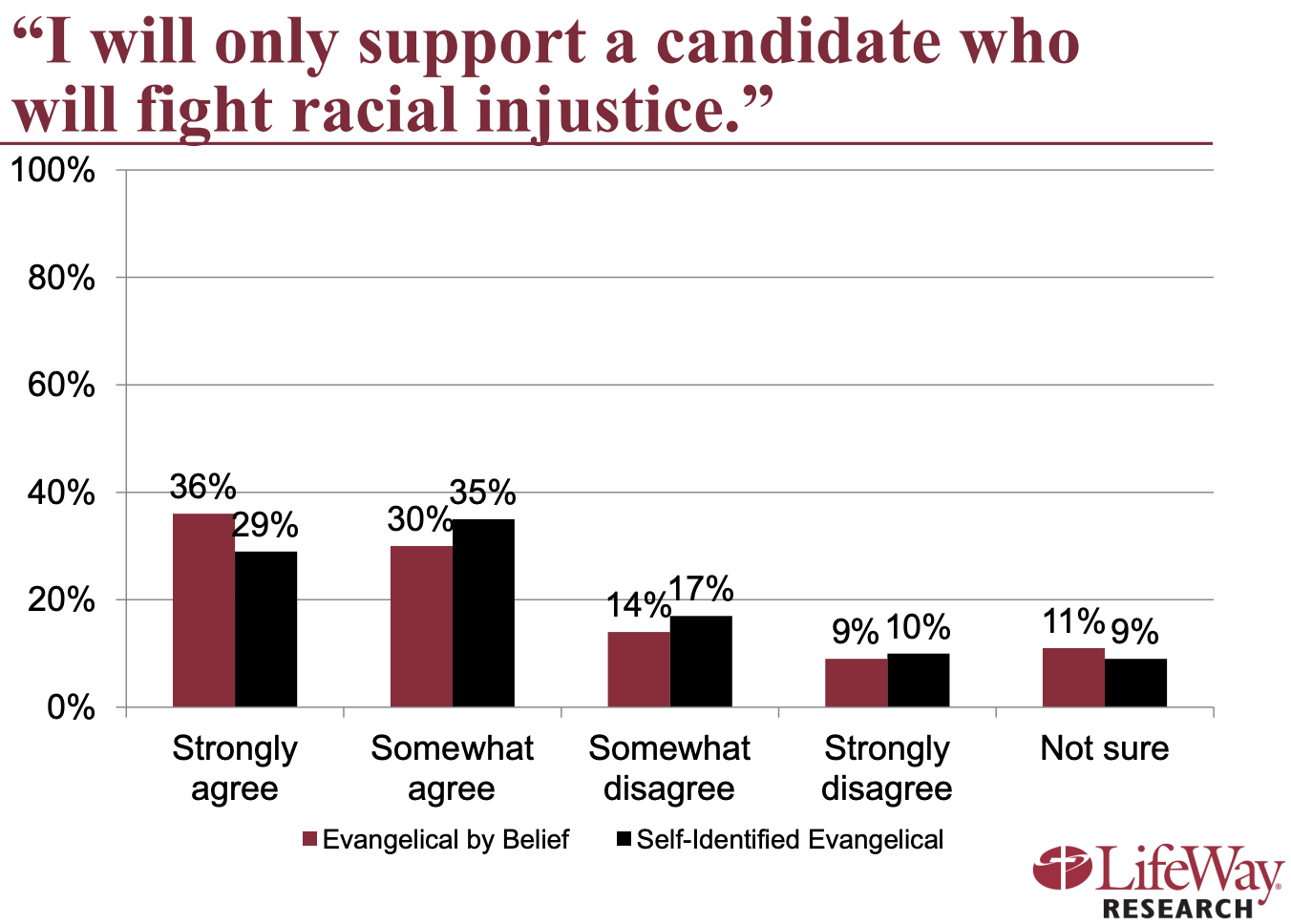

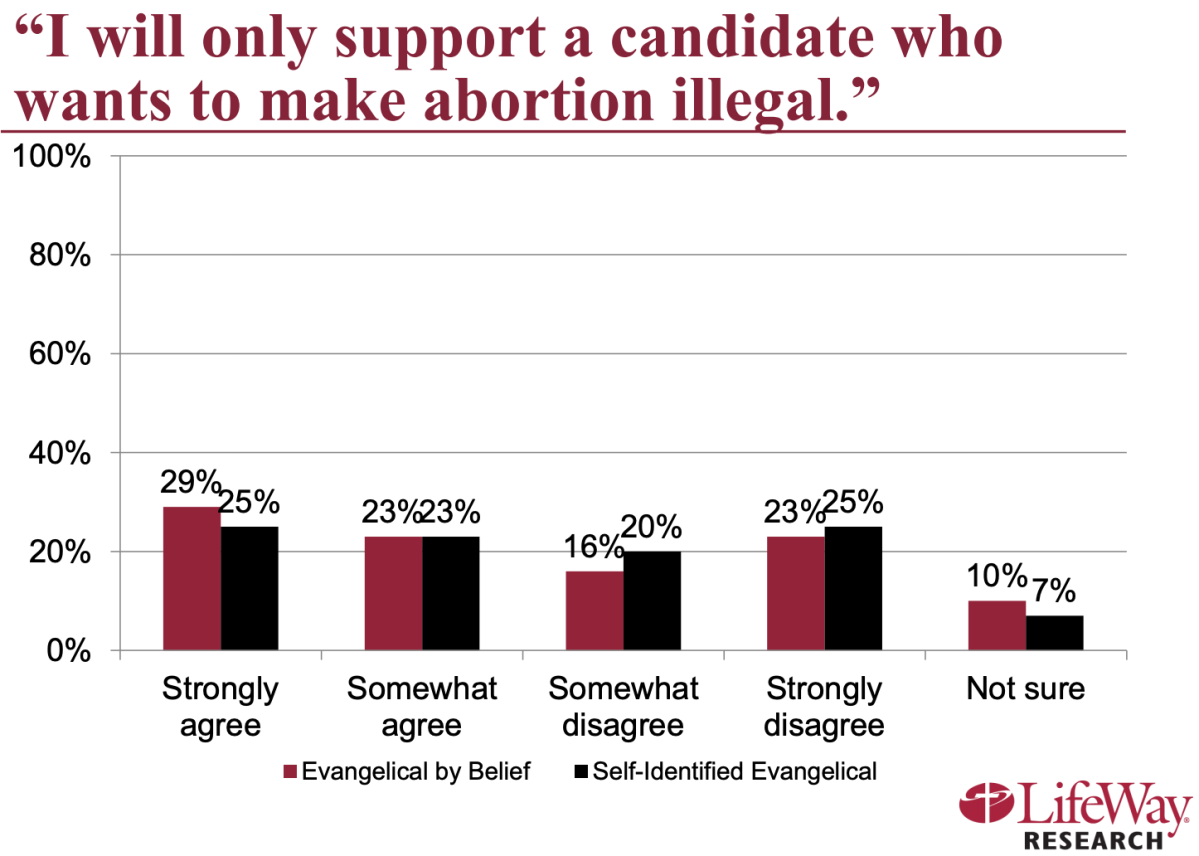

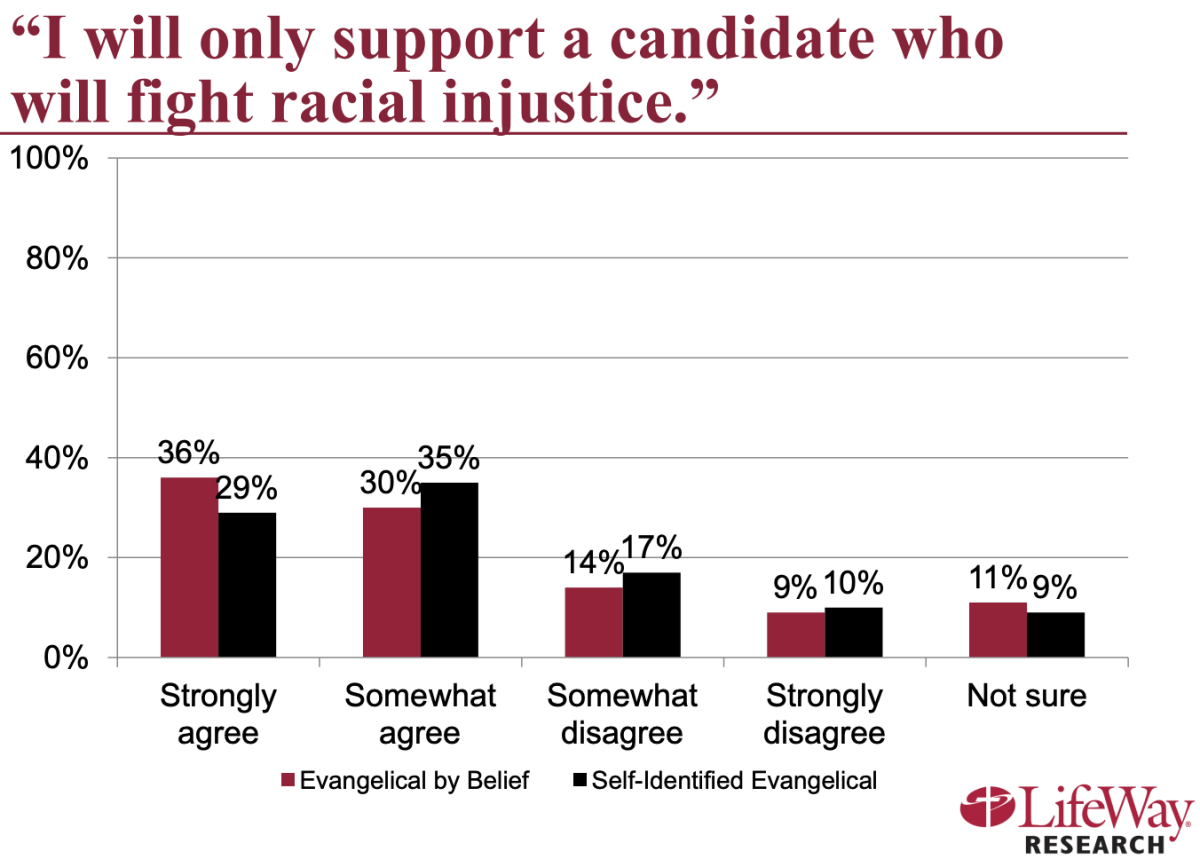

In the report released today, 52 percent said they “will only support a candidate who a wants to make abortion illegal” and 64 percent said they “will only support a candidate who will fight racial injustice.” Self-identified evangelicals reported similar stances, with 52 percent requiring a pro-life candidate and 66 percent requiring one against racial injustice. LifeWay’s designations represent a multiethnic sample.

Lead researcher Scott McConnell noted that abortion still outranks racial justice on a short list of significant issues for evangelicals. Yet, Christians on both sides of the political spectrum agreed that growing attention around racial justice as a political priority would represent a shift for white evangelicals in particular.

“It would be an invited change,” said Justin Giboney, a Democratic political strategist and cofounder of the AND Campaign, an effort calling Christians to advocate for both social justice and “values-based policy.”

Dallas pastor Robert Jeffress, a vocal supporter of President Donald Trump, said evangelicals care about racial justice, but it’s a “false dichotomy” to suggest Christians “are going to try to fight for social justice instead of the rights of the unborn.” He predicted Trump’s evangelical support will increase in the 2020 election, based in part on his pro-life record—and despite allegations he has been racially insensitive.

LifeWay Research’s Courage, Civility, and our Democracy report, sponsored by the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission (ERLC), follows the denomination’s “Gospel Above All” emphasis, encouraging Southern Baptists to transcend political divides following infighting over Trump’s election and presidency.

The survey, conducted in November 2018, also signal evangelicals’ concerns over candidates’ personal integrity and willingness to dialogue with those holding opposing political views.

ERLC President Russell Moore said the results “were occasionally encouraging, frequently surprising, and in some cases indicting.”

“What the responses clearly show is that there are forces driving apart those within the church,” he said. “That shouldn’t surprise us. But it should convict us. My prayer is that this survey and report would be one among many initiatives that can help show us the way forward and help us learn to love one another and stand with courage in the public square.”

Abortion and racial justice

Moore, a Trump critic in 2016, has written that both pro-choice views and lack of commitment to racial justice disqualify a candidate from receiving his vote, even if that means he has to vote for a third-party candidate or write someone in.

The new statistics on voter commitment to racial justice and the sanctity of life, McConnell said, may need to be nuanced before conclusions can be drawn. Some evangelical voters likely did “not want to fully agree” with the statements presented on the survey because they “have had to compromise on these positions in the past.”

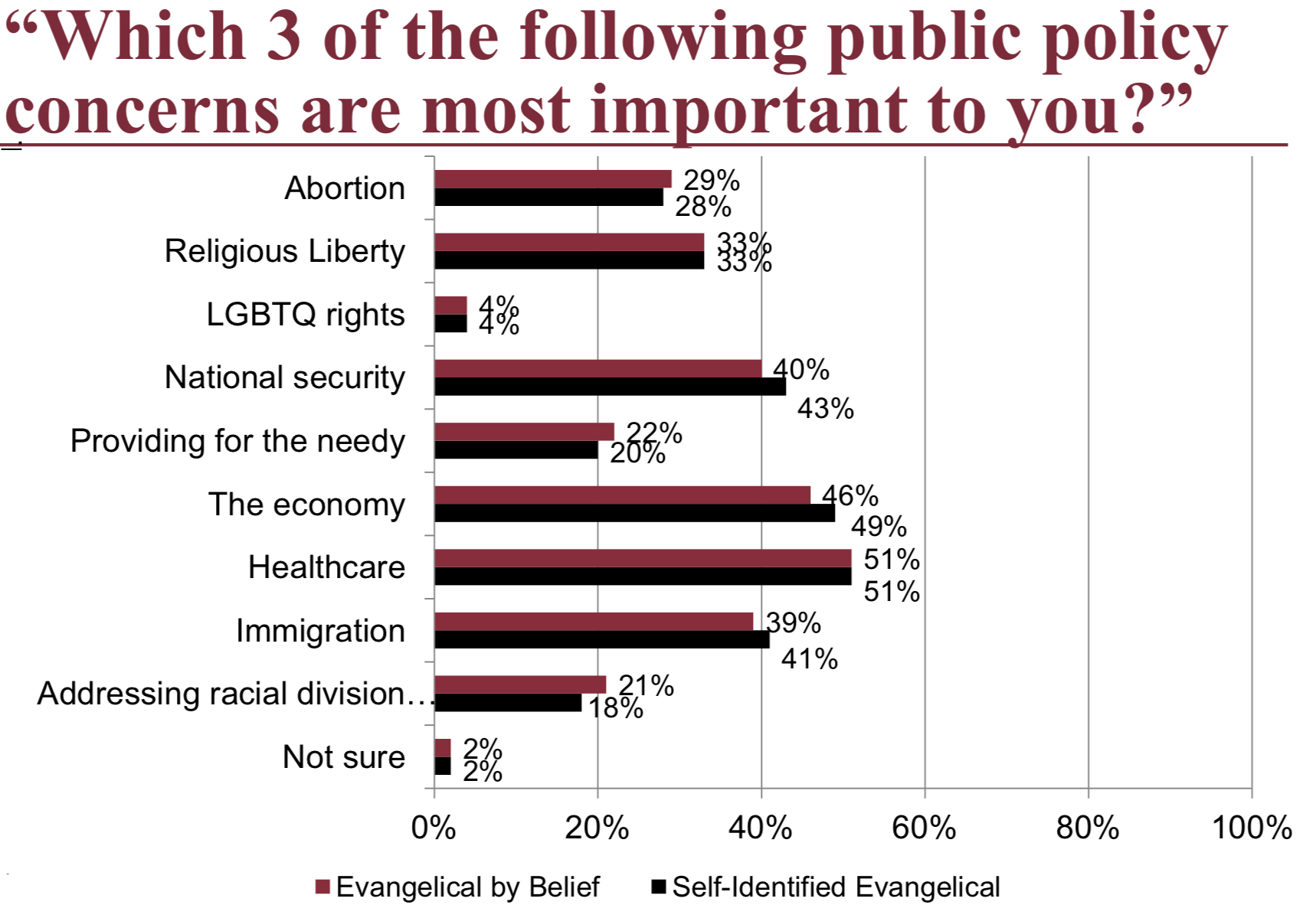

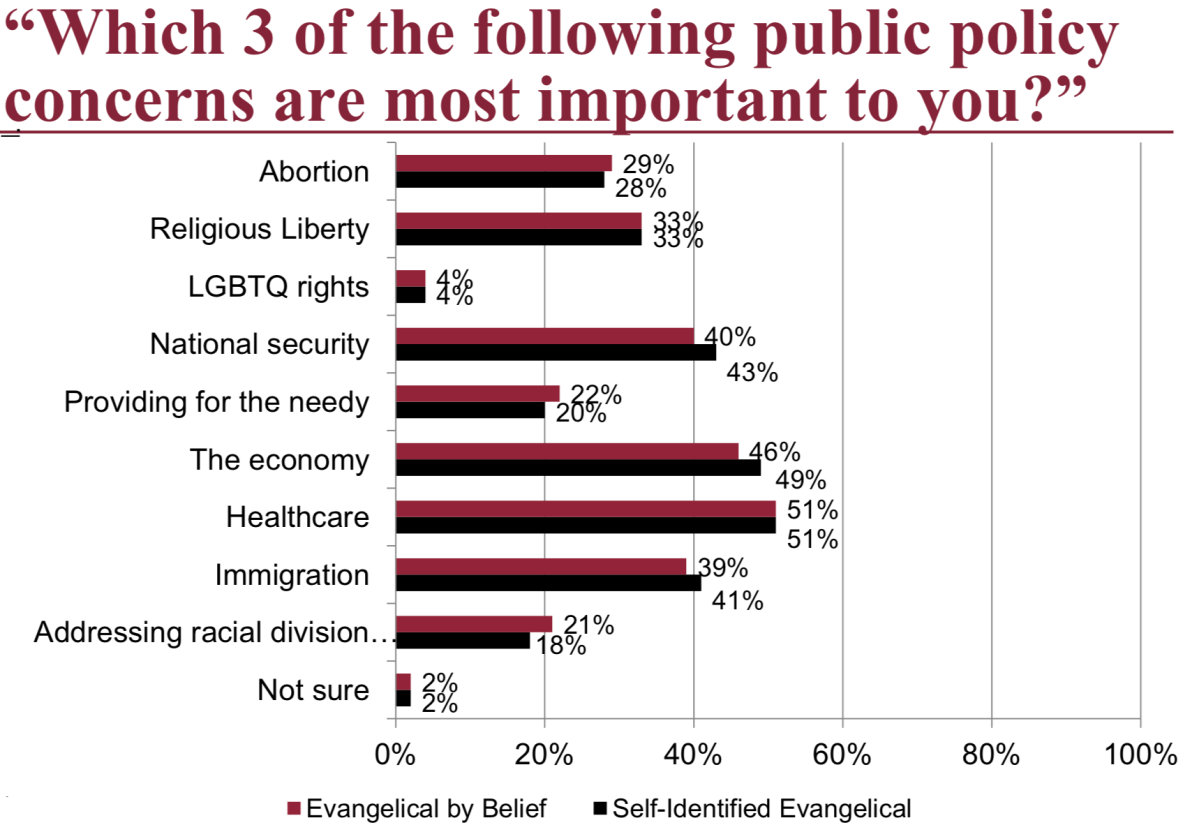

Additionally, when asked to select their top three “public policy concerns” from a list, more evangelicals by belief selected abortion (29%) than addressing racial division (21%). Among self-identified evangelicals, abortion (28%) topped addressing racial divisions (18%) as well.

Still, neither led the list of evangelicals’ top political concerns. For evangelicals by belief, that designation went to health care (51%) and the economy (46%). The findings agree with other data suggesting evangelical political priorities tend to mirror those of American voters overall.

In a separate LifeWay Research poll in 2016, 36 percent of evangelicals by belief and 31 percent of self-described evangelicals said a presidential candidate’s position on abortion influenced their vote. There is no comparative 2016 data on racial justice because the latest poll marked the first time that issue was included in a list of reasons for selecting a candidate.

“As we discussed current issues that could be motivated by biblical convictions among evangelical voters, fighting racial injustice appeared to be an important one to test,” McConnell said.

Race marked a significant dividing line when it came to the relative priority of abortion and racial justice for evangelical voters in 2018. Both African American (79%) and Hispanic (74%) evangelicals by belief were more likely than their white counterparts (61%) to say they will only support a candidate who will fight racial injustice.

The trend reversed when abortion was at issue. White (59%) and Hispanic (53%) evangelicals by belief were more likely African Americans (29%) to say they will only support a candidate who wants to make abortion illegal.

“We kind of put the social justice issues or civil rights issues above some of the pro-life issues from time to time—and sadly,” said Giboney, who is African American. “We would like to get to a time where we don’t have to make that kind of false choice.”

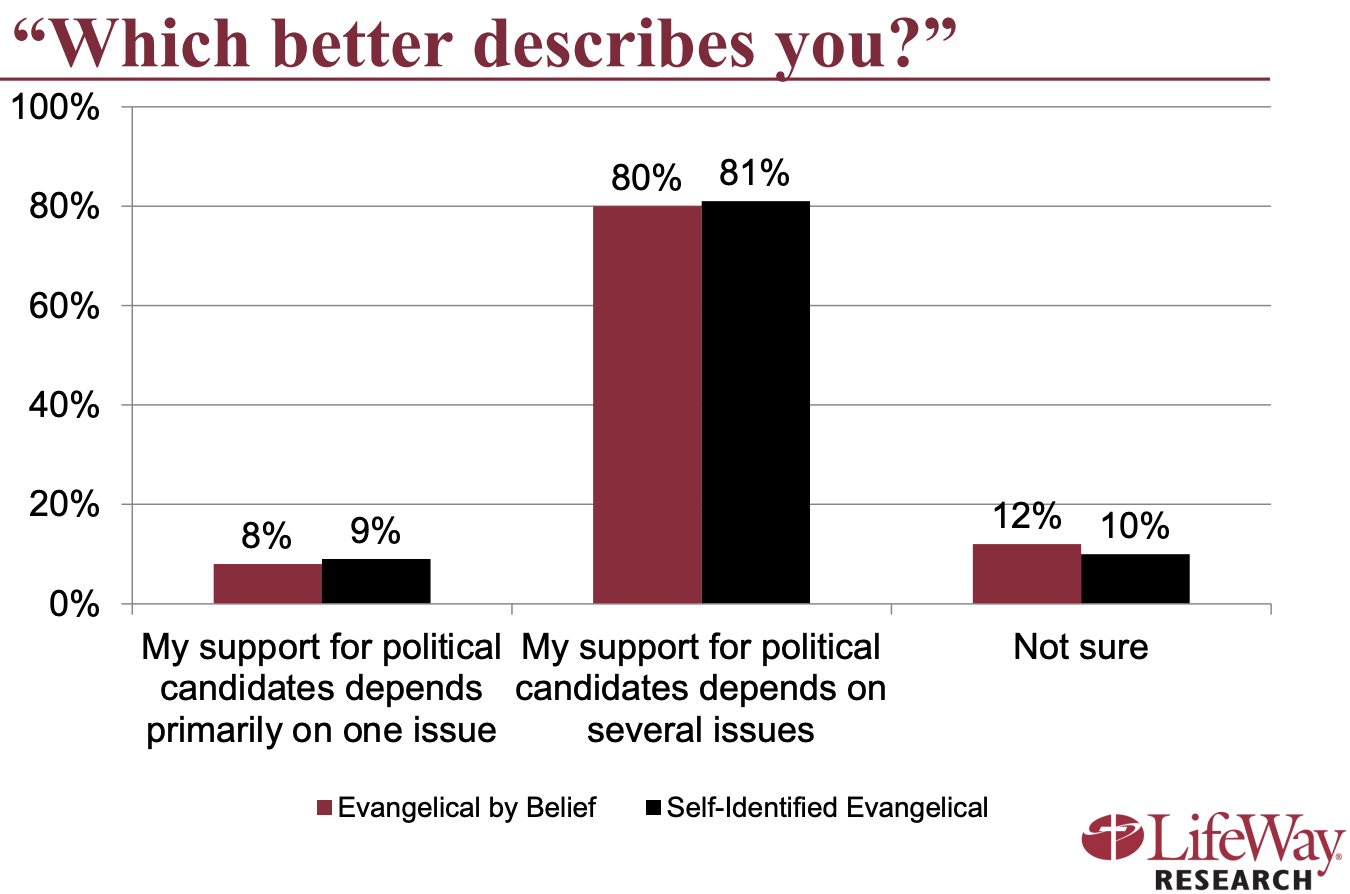

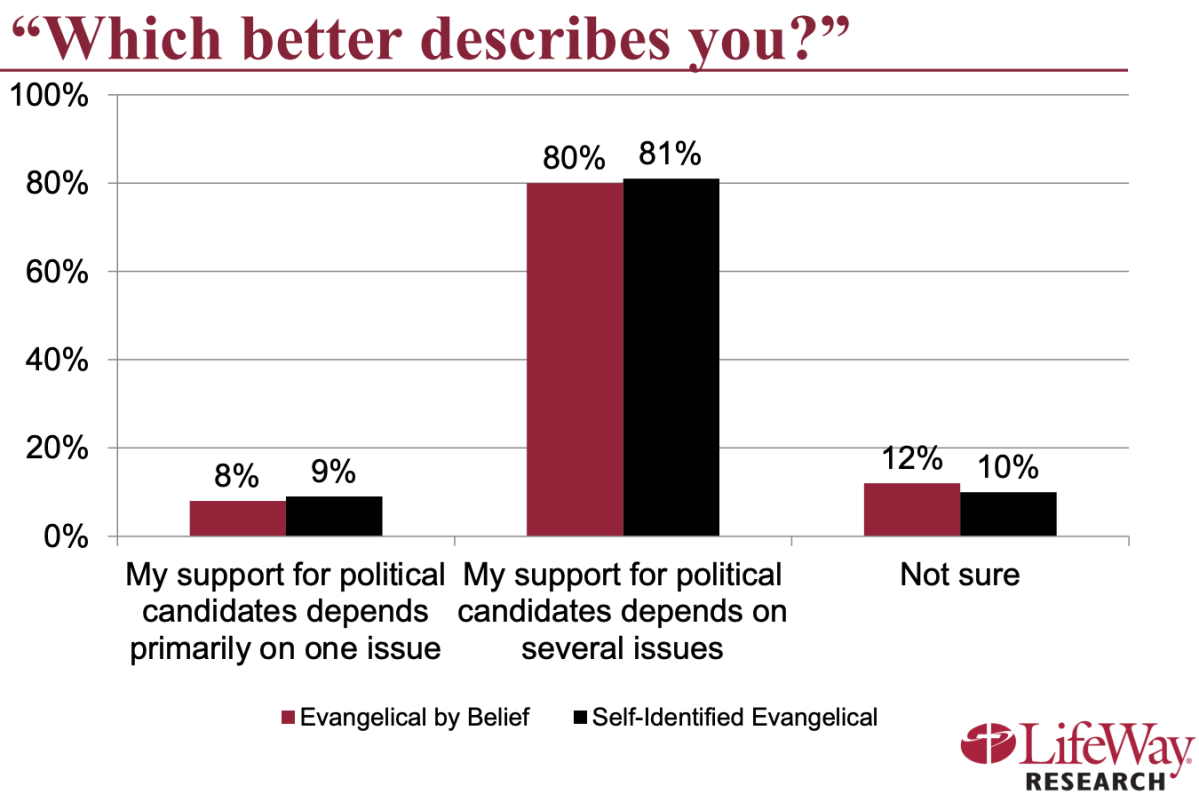

Despite the poll questions about baseline issues for supporting a candidate, a full 80 percent of evangelicals by belief and 81 percent of self-described evangelicals said their support depends on several issues rather than a single issue.

A 72-page ERLC report released in tandem with the LifeWay Research data and authored by Georgetown University international affairs professor Paul Miller cited “the obvious and troubling racial and ethnic fault line” identified by the polling. Yet on a positive note, the report stated, “With our witness sprinkled across the political spectrum, we can hold all sides to account for their particular weaknesses.”

Character and integrity

Another potential shift among evangelicals concerned the role of a candidate’s personal integrity in voting calculus.

Strong majorities of both evangelicals by belief (85%) and self-identified evangelicals (87%) agreed they “will only support a candidate who demonstrates personal integrity.” Around a third said personal character influenced their votes three years ago in the presidential election, according to a previous LifeWay Research poll.

Today, 42 percent of both evangelicals by belief and self-identified evangelicals agree they “have publicly expressed disapproval” at “unacceptable words or actions” of a political ally.

Those findings came the week House Speaker Nancy Pelosi announced the launch of a formal impeachment inquiry of Trump, citing allegations he may have withheld aid from Ukraine to pressure officials there to investigate the son of political rival Joe Biden. Trump, who dismissed the impeachment inquiry on Twitter as “Witch Hunt garbage,” continues to enjoy strong evangelical support despite criticism of his character and actions from some in that constituency.

A segment of evangelical voters apparently is thinking about political engagement differently than fellow Republicans and fellow Trump supporters. A Morning Consult poll found that white evangelicals are significantly less likely than Republicans to want to see Trump as the GOP nominee next year: 55 percent versus 71 percent.

Jeffress, pastor of First Baptist Church in Dallas, worries that polls don’t capture the full level of support for the controversial leader. He said Trump told him 10 points can be added to any poll measuring his support “because people don’t want to be shamed by their friends and cohorts” for backing him.

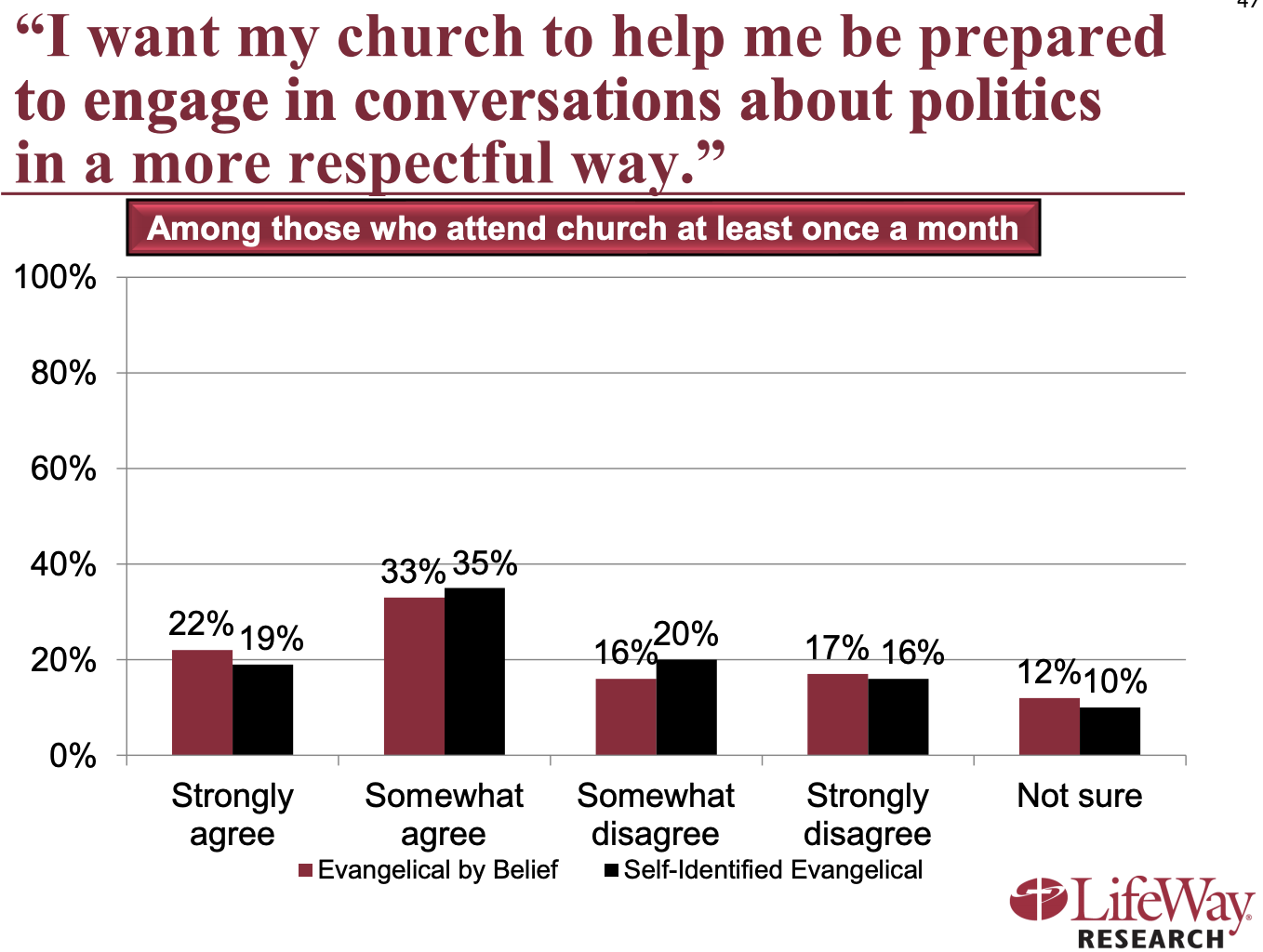

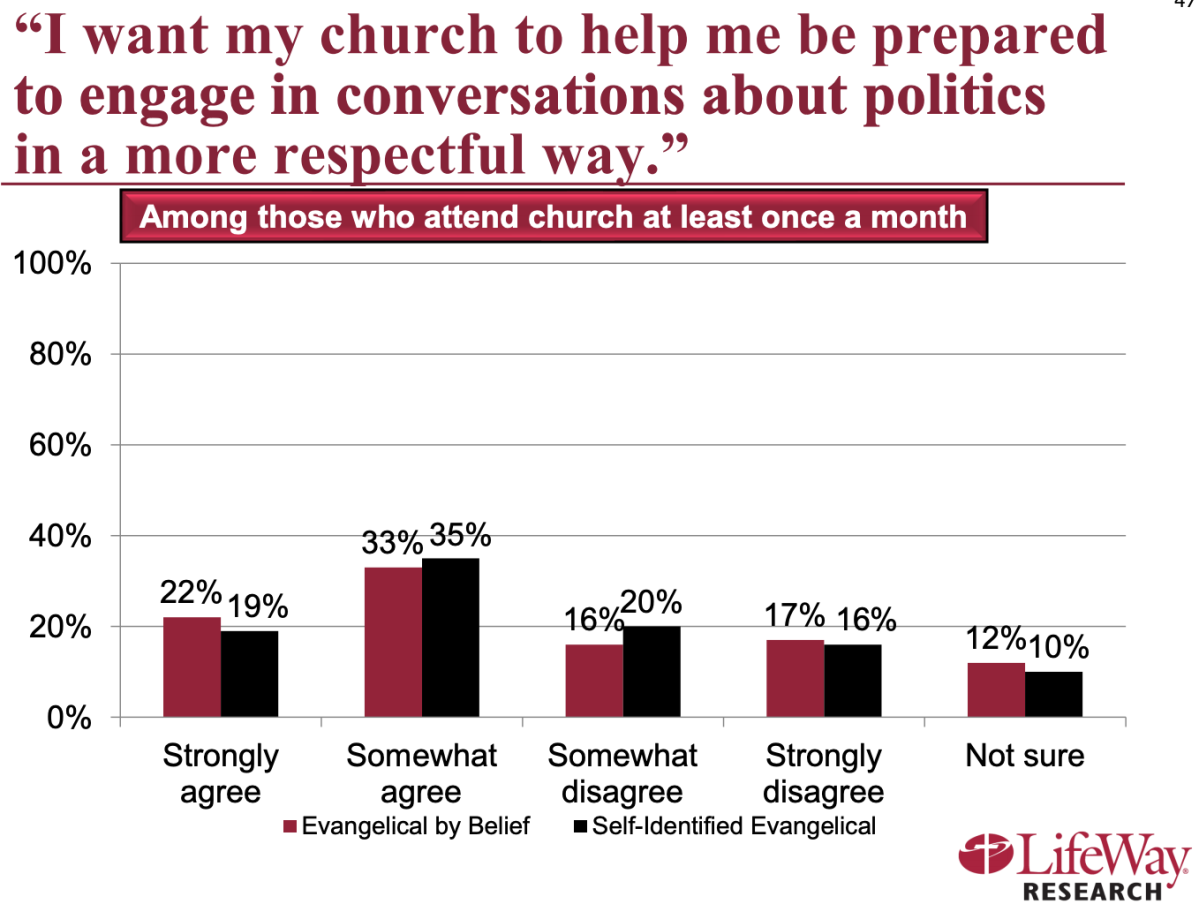

In the end, McConnell said, LifeWay Research’s latest data “raises the question of how individuals can achieve civility” amid their political disagreements.

“Higher levels of civility” correlate with “having the courage to speak up when your beliefs are unpopular, not thinking the worst of your opponent’s intentions, listening to diverse voices rather than only those who agree with you, not basing your vote on a single issue, and avoiding frequent engagement in social media about political and social issues.”

David Roach is a writer in Nashville, Tennessee