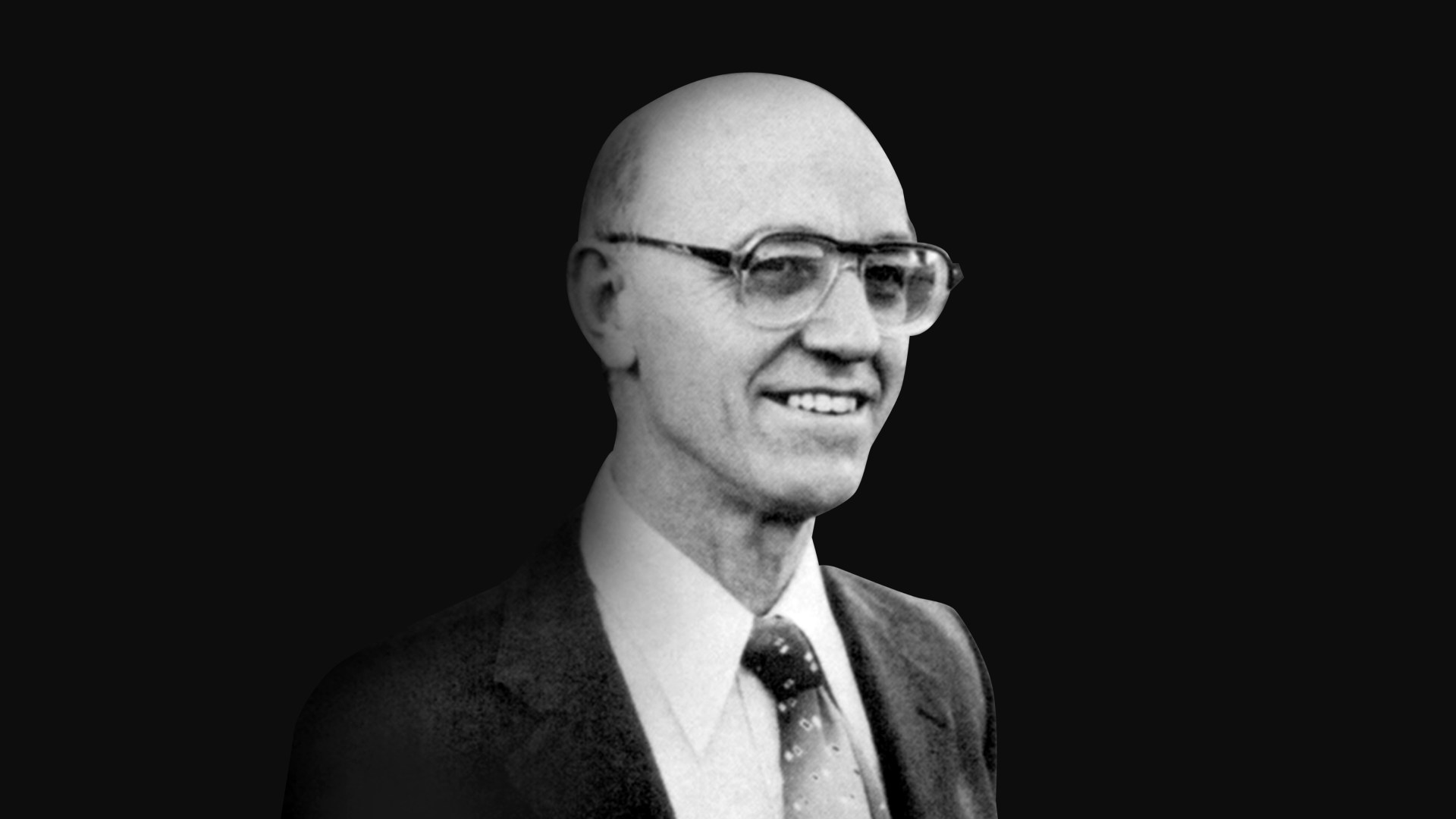

Francis I. Andersen, an Australian scholar who spent more than 35 years analyzing the syntax of the Hebrew Bible and created a powerful computer dictionary of the Scriptures’ clauses, phrases, and text segments, died last month at the age of 94.

Andersen started transcribing the oldest complete Hebrew text of the Bible into machine-readable form in 1971. It took him eight years to finish. Working with A. Dean Forbes, a seminary graduate who was researching a computer’s ability to recognize speech, Andersen developed a database of all the orthographic units of Hebrew Scripture, with seven different layers of syntactical information.

Today, the Andersen-Forbes database is used by Logos Bible Software, with a syntax search engine and phrase-marker graphs that open up the grammatical structures of ancient Hebrew. It is one of the research tools available in the “Clergy Starter” package, as well as other Logos software.

The database demonstrated the vast potential for digital Bible study just as the personal computer was being developed and made widely available. It was also a feat of Hebrew linguistics and Christian devotion.

Stuart Barton Babbage, an evangelical Anglican leader in Australia and one of Andersen’s spiritual mentors, said that Andersen “brought the machines of science into the service of the Church and the proclamation of the Word of her Lord.”

Andersen was also the author of the Anchor Bible commentary on Habakkuk, and co-author, with David Noel Freedman, of the series’ commentaries on Hosea, Amos, and Micah. Andersen loved the academic problems of understanding ancient Hebrew, but those who knew him said his deepest motivations were evangelical.

“Right to the end Frank loved to talk about the Scriptures, the different forms of Hebrew that could be seen in the books of the Bible, and what was going on in the world of scholarship,” wrote Andrew Prideaux, a campus minister at the University of Melbourne. “But most of all, Frank wanted to talk about the goodness and love of God.”

Andersen was born in Warwick, Queensland, Australia, in July 1925. He remembered his rural childhood as happy and wholesome, with people helping each other through droughts and depressions, regularly reciting the Lord’s Prayer, and singing “God Save the King” at parties.

His cultural Christianity became personal at the University of Melbourne, where Andersen earned a master’s degree in chemistry, enrolled in a doctoral program, and then felt God prompting him in a different direction. Babbage, who was friends with C. S. Lewis and a supporter of Billy Graham, encouraged Andersen to switch from the sciences to the humanities. Andersen got a degree in Russian and then, with more encouragement from Babbage, agreed to take a position teaching at Ridley College, an evangelical Bible school in Melbourne.

The school didn’t need a Russian scholar, but it did need someone with expertise in the Old Testament. Babbage said evangelical scholarship had been “plagued with pedantry” and needed someone who “could bring a touch of originality and creativity to the discussion of controverted issues or the solution to textual obscurities.”

As he later recalled, “Frank needed little encouragement.” Andersen decided to re-direct his academic career again and become an expert in Hebrew linguistics.

He went to Johns Hopkins University on a Fulbright scholarship in 1957 to study with William Foxwell Albright, the Methodist expert in biblical archaeology who had authenticated the Dead Sea Scrolls in the late 1940s. Andersen also worked closely with William Lambert Moran, a Jesuit scholar who showed how the study of obscure cuneiform texts from ancient Egypt could illuminate grammatical problems in Biblical Hebrew.

Andersen returned to Ridley in 1960 but only stayed for three years before he accepted a position at Church Divinity School of the Pacific, the Episcopal seminary in Berkeley, California. He taught classes on the Old Testament and continued researching arcane grammatical problems. His first major academic work was titled The Hebrew Verbless Clause in the Pentateuch. Then he wrote The Sentence in Biblical Hebrew.

At the same time, Andersen began his groundbreaking work using a computer to study the Bible. The seminary was part of the Graduate Theological Union, which connected Andersen to professors and students at seven other institutions in the area. It was also located near Silicon Valley, the emerging center of technological innovation, where people were figuring out how to make silicon semiconductors, integrated circuit chips, and microprocessors, as well as ways to network computers to share information. Andersen connected with A. Dean Forbes, who had graduated from Pacific School of Religion, one of the seminaries in the consortium, and then got a job as a project manager at Hewlett-Packard Laboratories in Palo Alto.

The two men started computerizing the syntactical information from Hosea, Amos, and Micah. Andersen and Forbes finished the first syntactical concordance in 1972 and then started on Ruth and the rest of the minor prophets. When they finished those in 1976, they began work on Jeremiah.

At the time, it was not clear how the computer concordances would be useful. They could not be made available to pastors or even most Bible scholars, who didn’t have access to research computers. But David Freedman, Andersen’s collaborator on three Anchor Bible commentaries, recalled being amazed at the “incalculable quantities of esoteric analytical data” the computer concordances could produce on the understudied minor prophets. And the possibilities presented by the advancing computer technology were too exciting to ignore.

“His delight and enthusiasm for his self-appointed task of creating new and extraordinary Bible dictionaries [were] contagious,” recalled scholar E. Ann Eyland. “His imagination in his choice for tools and methods has resulted in work of inestimable value for Biblical scholarship.”

Andersen left Berkeley after 10 years and took an academic position in New Zealand and then Australia. He returned to the United States in 1988 to teach at the New College for Advanced Christian Studies, in Berkeley. He taught at Fuller Theological Seminary from 1993 to 1997, before retiring to Melbourne at the age of 72.

As Andersen worked on obscure grammatical problems of Hebrew Scripture, he also reflected on the spiritual importance of his work. He wrote religious poetry in conversation with his translations and his own devotional experiences.

“You know how brokenly and with what shame / my tongue took on your dreadful, mighty name,” Andersen wrote in one poem, referencing his work on the Hebrew in Exodus 15:26. In another poem, Andersen wrote, “I love you, Yahweh, and with merry mind / and singing hands shout, ‘Joy! You are my Joy!’”

Andersen’s piety and scholarship were fused in his commentary on Job, which he published with InterVarsity Press. He analyzed the structure of the text, and well as the ancient poetic language. But Andersen made clear that those tasks were interesting and important to him because he believed the text was a revelation of God.

“It is presumptuous to comment on the book of Job,” he wrote in the introduction to his commentary. “It is so full of the awesome reality of a living God. Like Job, one can only put one’s hand over one’s mouth (40:4). But God has revealed himself, preserving at the same time the inaccessible mystery of his own being. So we must attempt this impossible thing which he makes possible (Mark 10:27). However forbidding, he fascinates us irresistibly until, by ‘kindness and severity’ (Rom. 11:22), he brings us in his own way to Job’s final satisfaction and joy.”

One of Andersen’s sons died shortly after he finished the book. His wife, Lois, died in 2010. Andersen is survived by his sons David and John, daughters Nedra and Kathryn, and his second wife, Margaret.