Why is Christianity growing in some countries but declining in others?

For much of the 20th century, social scientists answered this question by appealing to the so-called secularization thesis: the theory that science, technology, and education would result in Christianity’s declining social influence.

More recently, some scholars have suggested the cause is rather the accumulation of wealth. Increasing prosperity, it is believed, frees people from having to look to a higher power to provide for their daily needs. In other words, there is a direct link from affluence to atheism.

In a peer-reviewed study published this month in the journal Sociology of Religion, my coauthor and I challenge the perceived wisdom that education and affluence spell Christianity’s demise.

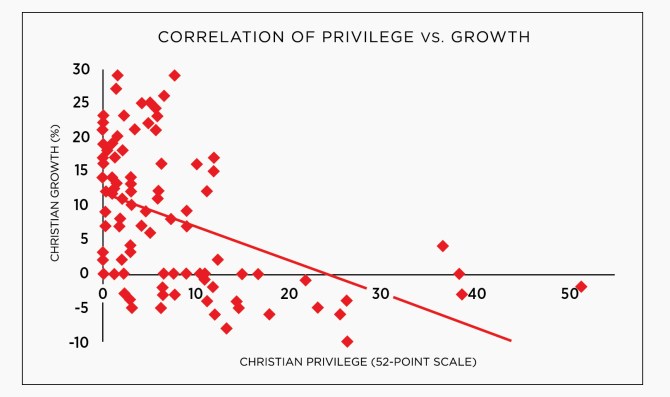

In our statistical analysis of a global sample of 166 countries from 2010 to 2020, we find that the most important determinant of Christian vitality is the extent to which governments give official support to Christianity through their laws and policies. However, it is not in the way devout believers might expect.

As governmental support for Christianity increases, the number of Christians declines significantly. This relationship holds even when accounting for other factors that might be driving Christian growth rates, such as overall demographic trends.

We acknowledge that our methodology and datasets cannot account for a factor of great importance to Christians: the movement of the Holy Spirit. However, our numerous statistical tests of the available data reveal that the relationship between state privilege of Christianity and Christian decline is a causal one, as opposed to only correlation.

Our study notes three different paradoxes of the vibrancy of Christianity: the paradox of pluralism, the paradox of privilege, and the paradox of persecution.

1. The paradox of pluralism

Many Christians believe that the best way for Christianity to thrive is to shut out all other religions. Ironically, though, Christianity is often the strongest in countries where it has to compete with other faith traditions on an equal playing field.

Perhaps the best explanation for this is derived from The Wealth of Nations, the most important work of Adam Smith. The famous economist argued that just as a market economy spurs competition, innovation, and vigor among firms by forcing them to compete for market share, an unregulated religious marketplace would have the same effect on institutions of faith.

Just as iron sharpens iron, competition hones religion. Contexts of pluralism force Christians to present the best arguments possible for their beliefs, even as other faith traditions are forced to do the same. This requires Christians to have a deep knowledge of their beliefs and to defend them in the marketplace of ideas.

Our study finds that as a country’s commitment to pluralism rises, so too does its number of Christian adherents. Seven of the 10 countries with the fastest-growing Christian populations offer low or no official support for Christianity. Paradoxically, Christianity does best when it has to fend for itself.

The paradox of pluralism can be seen in the two world regions where Christianity is growing the fastest: Asia and Africa.

The strongest increase of Christianity over the past century has been in Asia, where the faith has grown at twice the rate of the population. Christianity’s explosive growth in this part of the world is even more remarkable when one considers that the region contains only one Christian-majority country: the Philippines.

How do we explain this paradox? In contrast to Europe, Christianity in Asian countries has not been in a position to receive preferential treatment from the state, and this reality has resulted in stunning Christian growth rates. The Christian faith has actually benefited by not being institutionally attached to the state, feeding its growth and vitality.

Consider the case of South Korea, which in the course of a century has gone from being a country devoid of Christianity to one of its biggest exporters. It currently ranks as the second-largest sender of missionaries, trailing only the United States.

This example illustrates well the paradox of pluralism. Because South Korea is not a Christian country, Christianity enjoys no special relationship to the state. In fact, Christianity in Korea endured the brutal persecution of Japanese colonial rule, during which churches were forcibly closed down and their properties confiscated. Indeed, the church persisted through poverty, war, dictatorship, and national crises throughout Korean history.

Since World War II, Korean Christianity has grown exponentially, with tens of thousands of churches being built and seminaries producing thousands of graduates every year. Today, about a third of the country is Christian.

Africa is the other world region where Christianity has seen breathtaking growth, particularly in recent decades. Today, there are nearly 700 million Christians in Africa, making it the world’s most Christian continent in terms of population. Indeed, the 10 countries noted above with the fastest-growing Christian populations in the world from 2010 to 2020 are all located in sub-Saharan Africa.

Christianity has made inroads into Africa not because it enjoys a privileged position with the state, but because it has to compete with other faith traditions on an even playing field. Of the countries where Christianity has seen remarkable growth, only one, Tanzania, has a level of official support for the religion that is at the global average. In the rest of the cases (including moderately ranked Kenya and Zambia), support for Christianity was below—and usually well below—the global average.

In short, Christianity in Africa, as in Asia, is thriving not because it is supported by the state but because it is not supported.

2. The paradox of privilege

Nine of the 10 countries with the fastest-declining Christian populations in the world offer moderate to high levels of official support for Christianity. While competition among religions stimulates Christian vitality, state favoritism of religion inadvertently suppresses it.

When Christians perceive a threat stemming from religious minorities, they may look to the state to give them a leg up on the competition. Such privilege can include funding from the state for religious purposes, special access to state institutions, and exemptions from regulations imposed on minority religious groups. Paradoxically, though, the state’s privileging of Christianity in this manner does not end up helping the church, according to our data.

Christians attempting to curry the favor of the state become distracted from their missions as they become engrossed in the things of Caesar rather than in the things of God to maintain their privileged stations.

Yes, favored churches may use their privileged positions to exert influence over the rest of society; however, this is accomplished primarily through rituals and symbols—civil religion—rather than spiritual fervor. For this reason, state-supported churches often become bereft of the spiritual substance that people who practice the faith find valuable, leading laypeople to leave.

Interestingly, some research even suggests that missionaries from state-supported churches are less effective than missionaries whose commissioning churches are independent of the state.

Scholars of religion have long noted that trends toward secularization appear strongest in the countries of the West, particularly in Europe, where the church for centuries played a major role in peoples’ lives. Numerous polls have documented the comparatively weak levels of creedal belief and attendance at religious services in this part of the world.

That Europe is the most secular region of the world—and also the richest—has led many to posit a causal relationship between affluence and the decline of Christianity.

Our study argues instead that the secularization of Europe stems centrally from the widespread support given to Christianity by the state.

In the United Kingdom, for example, the law established the Church of England as the state church and Christianity as the state religion, granting privileges not afforded to minority religious groups. Christian decline has also occurred in the Protestant nations of Scandinavia, where church-state relations have been marked by privilege (including past public subsidies). For example, the Church of Sweden long enjoyed a close relationship with the state (the two separated in 2000), with the Swedish king serving as the head of the church and the government appointing bishops to their positions.

A similar pattern can be seen in Catholic-majority states. For much of the 20th century, countries such as Portugal, Spain, Belgium, and Italy offered strong support to the Roman Catholic Church and actively discriminated against non-Catholics in the areas of family law, religious broadcasting, tax policy, and education. While Catholic privilege in these countries has weakened in many parts of Europe, the religious playing field remains unbalanced in important ways, especially with respect to the barriers to entry for new religious movements.

The relationship between political privilege and Christian decline is strongest in countries dominated by Eastern Orthodox forms of Christianity. For example, Russia has extended numerous privileges to the Russian Orthodox Church—such as funding for sacred sites, access to state institutions, and autonomy over its own affairs—even as it imposes restrictions on the Orthodox church’s competitors, including the denial of visas to foreign clergy, deportations of missionaries, and the withholding of land rights. Orthodox Christian countries like Russia are the most likely to integrate church and state.

The upshot is that churches in Europe do not have to worry about competing with religious competitors on an equal playing field. As a result, these churches have become lethargic, as they depend on the state for their sustenance.

Church attendance in these countries remains the lowest in the Christian world, despite the fact that the vast majority of citizens in these states retain their official church memberships. European churches have taken on a largely ceremonial function but play little role in peoples’ everyday lives. Resplendent cathedrals designed to cater to hundreds of people typically welcome only a handful of worshipers in their normal Sunday services.

In short, Christianity in Europe has been waning not despite state support but because of it.

3. The paradox of persecution

In the second century, Tertullian, an early church father, reached the astounding conclusion that “the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church.” Stunningly, our study finds that contexts of anti-Christian discrimination do not generally have the effect of weakening Christianity; in some cases, persecution even strengthens the church.

Like healthy religious competition, religious persecution—for entirely different reasons—does not allow Christians to become complacent. To be sure, in some cases, anti-Christian persecution has greatly damaged Christianity, such as in 7th-century North Africa, 17th-century Japan, 20th-century Albania, and modern-day Iraq. Yet in many other contexts of discrimination and persecution (short of genocidal violence), the church has defied the odds—not only continuing to exist but also, in some cases, even thriving.

In these environments, believers turn to their faith as a source of strength, and this devotion attracts those outside their faith.

Around the world, hundreds of millions of Christians live in countries where they experience high levels of persecution. Even so, Christianity continues to prove extraordinarily resilient, just as the early church under the sword of Caesar.

Today Christianity is growing rapidly in certain Muslim countries such as Iran and Afghanistan, where the faith experiences a high level of persecution. Open Doors ranks Iran as the eighth worst place in the world to be a Christian, with an “extreme” level of persecution. In the Islamic Republic, the government bans conversion from Islam, imprisons those who proselytize, and arrests those who attend underground house churches or print and distribute Christian literature.

Nevertheless, despite the government threatening, pressuring, and coercing Christians, the church in Iran has become one of the fastest growing in the world in terms of conversion. While it is difficult to determine exactly how many Christians live in Iran, given that most keep their faith secret for fear of persecution, it is estimated—backed by survey data—that there could be as many as a million Iranian believers. The faith’s startling growth in Iran has led to widespread concern among Iranian policymakers that Christianity threatens the foundation of the Islamic Republic.

A similar story has been playing out in Iran’s neighbor to the east, Afghanistan. Open Doors ranks the country as the second-worst place to be a Christian, behind only North Korea. As in Iran, it is illegal in Afghanistan to convert from Islam, and those who do so face imprisonment, violence, and even death. Christians confront persecution not only from the Islamist government but also from Islamist militants who target religious minorities. Afghan Christian communities have been battered by decades of war.

It is impossible to assign a precise figure for the number of Christians in Afghanistan. Nevertheless, the available evidence indicates that Christianity continues to grow, sustained by the existence of an underground church, despite the widespread and intense repression faced by Christians. Some reports indicate that Christianity has even spread among Afghan elites and members of the country’s parliament. One open example: Rula Ghani, the country’s First Lady, is a Maronite Christian from Lebanon.

Outside the Muslim world, the experience of the world’s largest persecuted church—the Chinese church—mirrors that of the early church under the sword of Caesar when it too experienced exponential growth.

During the first three decades of communist rule in China, the church was subjected to severe persecution, especially during the era known as the Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1976. Launched by Mao Zedong, the campaign sought to preserve communism in China by waging war against its perceived enemies, including religion. Hundreds of thousands of Christians, both Catholics and Protestants, perished during this time.

Yet Christianity persisted by going underground. Remarkably, Protestants even witnessed sizable growth by the end of the Cultural Revolution. Sociologist of religion Fenggang Yang notes that since 1950, Protestant Christianity has grown by a factor of 23. At least 5 percent of China’s population of nearly 1.5 billion people now subscribes to Christianity.

Yang predicts the percentage will grow exponentially over the next several years so that by 2030 China will have more Christians than any other country. By 2050, half of China could be Christian.

It is possible that future years may prove these projections to be too sanguine, as the Chinese Communist Party continues its massive crackdown on religious groups. But it is unlikely that repression in China will be able to curtail Christian growth altogether.

In short, the temptation of political privilege and not the threat of persecution appears to be the greater impediment to the Christian faith.

Lessons for Christendom

These paradoxes hold important ramifications for Christian communities around the world.

In Europe, politicians and political parties in Hungary, Italy, Poland, Slovenia, France, Austria, Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland have called for deepening the relationship between Christianity and their governments. Some successful politicians have positioned themselves as defenders of Christianity against an alien Islamic faith that threatens the Christian integrity of their respective countries.

In many cases, right-wing populist parties have proven capable of increasing their share of the vote, in part owing to their defense of the “Christian nation.” If such trends continue, we can expect to see the further corrosion and decline of Christianity in this part of the world for the reasons described above.

A similar story can be seen across the Atlantic. Christianity in the United States, and in particular the evangelical movement, stands today at a very precarious crossroads.

While the US, unlike its European counterparts, does not have official state support for religion, this does not mean that Christianity has not become entangled with the state. As Christianity has become increasingly intertwined with partisan politics, the US has been undergoing a simultaneous decades-long decline in religiosity—a trend confirmed in a number of scholarly studies.

Over the past 30 years, the US has witnessed a sharp increase in the number of religiously unaffiliated Americans, from 6 percent in 1991 to 23 percent today, even though the American population as a whole has experienced significant growth during this time. Our argument suggests that this rise in the religiously unaffiliated owes, in part, to attempts by Christians to curry the favor of the state (and sometimes receiving it).

Conservative Christians initially became involved in politics in the 1970s as a way to fight against the erosion of “Christian values” in society and to “take America back for God.” To this end, they became embroiled in partisan politics.

The intertwining of religion and politics in this way, however, has repelled people from Christianity who see the Christian faith as supporting a certain kind of politics they personally disagree with. As a result, politicized Christianity is able to appeal to an increasingly narrow group of individuals, even as it drives liberals and moderates away from the church.

The sacralization of politics suggests that the US may be headed down the same path as its European counterparts. The good news for concerned Christians is that, if our research and analysis are correct, it may be possible to reverse trends toward secularization.

This would require institutions of faith to shun the temptation of privilege and to not see religious competition as threatening and something to be shut out. Such an approach would not require Christians to segregate themselves from public life or to abandon politics altogether; however, it would strongly caution Christians against equating any political party, political ideology, or nation with God’s plans.

Our research suggests the best way for Christian communities to recover their gospel witness is to reject the quest for political privilege as inconsistent with the teachings of Jesus. In doing so, they would show that they take seriously Christ’s promise that no force will be able to prevail against his church. And rejecting privilege will make believers more reliant on the Holy Spirit to open hearts to the gospel message.

Nilay Saiya is assistant professor of public policy and global affairs at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. He is author of Weapon of Peace: How Religious Liberty Combats Terrorism (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

Speaking Out is Christianity Today’s guest opinion column and (unlike an editorial) does not necessarily represent the opinion of the publication.

Correction: A previous version of this article misstated that the Swedish king remains the head of the Church of Sweden and appoints bishops. The church and the state separated in 2000.