When Jean Bouchebel retired at age 70, he was not ready to simply relax.

Instead, he still works full time and wakes at 2 a.m. for prayer and meditation.

From an orphanage in Lebanon to leadership at World Vision, God’s faithfulness saved Bouchebel multiple times from death during the worst days of civil war. Through his service, thousands of refugees have received the food, clothes, and shelter they needed to stay alive.

But his morning discipline is not monastic piety. The daily hour-long prayer at his home in Texas precedes meetings with pastors and partner organizations eight time zones ahead in Lebanon.

With his son, Patrick, in 2012 Bouchebel founded Witness as Ministry after working 27 years with World Vision International, first in Lebanon and then at its headquarters in California. During the height of the war in Syria, when more than 2 million refugees flooded across the border into Lebanon, he could not contemplate the leisure of retirement.

Refugees were living in tents in the snow.

Children lacked adequate footwear.

People were hungry.

Drawing on skills he had learned at World Vision, Bouchebel shipped 40-foot containers to Lebanon filled with medical equipment, clothing, hygiene kits, and food. Over 1,000 meals a day were provided to needy refugees.

And amid an economic collapse exacerbated by last summer’s explosion in Beirut’s harbor, relief work has extended to the Lebanese. Church partners have served Muslim and Christian without discrimination, giving out nearly 3,000 food parcels to families, providing medical services for 3,600 people, and repairing 168 neighboring homes.

Donald E. Miller

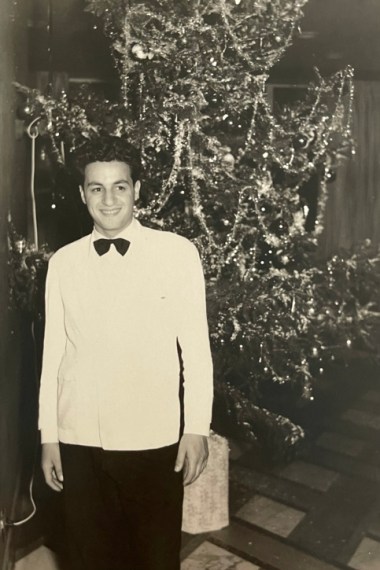

Donald E. MillerBorn in 1942 in the mountain town of Bikfaiya, Bouchebel shared a home with his five siblings, parents, grandparents, aunts, and uncles. But when he was eight years old, his father died and his mother fell ill.

The family solution was to place the children in different orphanages. Six years later, his mother passed away. At age 14, Bouchebel assumed responsibility for his siblings, working at a hotel as a dishwasher. His modest $3 monthly salary helped to provide clothing, bedding, and books for his brothers and sisters.

At age 17, Bouchebel moved to a different hotel as a busboy, with a better salary. But realizing the limitation of his education and future prospects, he took English courses at the local YMCA and later learned German from a tutor as the hotel had many guests flying in on the Lufthansa airline.

Three years later, his fluency in Arabic, French, English, and German landed Bouchebel a job as a waiter at the prestigious InterContinental Hotel—the best in Lebanon. He rapidly advanced, becoming a maître d’ (headwaiter) in the dining room, then assistant food and beverage director, and eventually the director of the entire department for the 600-bed facility.

Courtesy of Jean Bouchebel

Courtesy of Jean BouchebelBut despite his success, he felt a void in his life. While questioning his purpose and what happened after death, Bouchebel was introduced by a friend—who had a radical life change after converting to Christianity—to a couple who read the Bible with him, which had not been his practice as a Roman Catholic. Shortly thereafter, he went to a revival meeting at a local church and gave his life to Jesus.

“I have lived 30 years of my life wanting to make a future for myself,” Bouchebel recalls praying. “From this day on, I would like to live for you.”

Two years later, the civil war started in Lebanon. Tourism ground to a halt, as 120,000 people were killed between 1975 and 1990. The InterContinental reduced its staff to five key people, including Bouchebel. They met daily but had no guests to serve.

After several months, he heard from God.

“I felt the Lord pushing me—as if two hands were pushing me to get out of the hotel,” he said. “I couldn’t understand what was happening, but I realized at the end that God didn’t want me to stay.”

At breakfast, Bouchebel told the general manager he would take his holiday leave and come back when the business picked up again. Irate, his boss fired him and told him never to return.

That same evening, a militia set the hotel on fire, killing his remaining colleagues. Bouchebel became convinced that God’s hand was on him, cementing a conviction that God had a purpose for his life.

After nine months of unemployment for Bouchebel, the InterContinental Hotel in Saudi Arabia offered him a job. Desperate for an income, he left his wife and two young children behind in Lebanon with extended family, negotiating with the hotel to return home every three months.

Over the next four years, Bouchebel rose rapidly, directing the food and beverage service in three branches. But his visits home troubled him, as he witnessed increasing scenes of poverty and displacement brought on by the civil war.

God then told him to again leave a secure hotel job in order to serve those in need.

“I will never leave you; I will never forsake you,” he recalls God assuring him. “I will provide for you, and I will provide for your ministry.”

But first Bouchebel had to wait—and learn dependence.

He returned to Lebanon in 1980, and for four years he was unemployed. The family survived on savings while farmland neighbors brought them fruits and vegetables.

Waiting on God for direction, Jean was given a full scholarship at Arab Baptist Theological Seminary and reconnected with the friend who initially led him to the Lord.

And then direction came.

“Jean, you have nothing,” said his friend. “Why don’t you serve God in the Palestinian camps?”

Initially afraid for his safety, as Palestinians and Lebanese Christians were on opposite sides of the civil war, Bouchebel was warmly greeted by a poor family when he entered the camp. (About 100,000 Palestinians fled to Lebanon during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, neither permitted to return nor to fully integrate into Lebanese society.) For the next year, he visited regularly, sharing Christian literature along with his own meager resources.

Meanwhile, World Vision had also begun relief work in Lebanon. But as foreign diplomats, teachers, and charity workers increasingly became targets of kidnapping, the NGO needed to hire a local person to manage its operations. Noticing Bouchebel’s work in the camps and impressed by his business background, World Vision asked if he would direct its Lebanese program on an interim basis.

Fifteen years later, and responsible for a region that included Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, Cyprus, and Greece, Bouchebel’s World Vision budget had grown from $300,000 to $30 million.

“The Lord honored me,” he said. “When God makes a promise, he is faithful.”

Bouchebel extended this faithfulness liberally, eventually working through the leadership of 11 different Christian denominations, as well as the Muslim Shiite, Sunni, and Druze communities.

Donald E. Miller

Donald E. MillerBut God would first have to save his life again.

Crossing Beirut from its Muslim east to its Christian west in 1985, Bouchebel and his family were stopped at a checkpoint. His 15-year-old son was beaten, and his 10-year-old daughter seized. Taking all of them to a nearby olive garden, the militiaman told Bouchebel’s wife and children to say goodbye.

But first, taking the $3,000 Bouchebel was carrying for World Vision relief, the man patted him down in search of more—and his hands discovered a pocket New Testament.

“What’s this?” demanded the guard.

“Do you really want to know?” asked Bouchebel. Opening the Bible, he read from John 3:16.

The militiaman grabbed the book and threw it down to the ground. But he then told Bouchebel to take his family and leave. He even gave him $20 for taxi fare.

“God snatches people from death,” said Bouchebel, “if he still has a purpose for them.”

Lebanon’s war ended in 1990, and nine years later Bouchebel and his wife relocated to Southern California. For another 13 years, he worked in the international office of World Vision as its director for resource development, extending his Middle East service to Africa and Latin America.

Now 79 years old, Bouchebel’s heart remains broken. Conflicts in the Middle East are unceasing, and he is especially troubled by their impact on the church. In 1943, a newly independent Lebanon was 55 percent Christian. Today it is 30 percent Christian or less, with continual migration.

This situation is echoed in Syria and Iraq. At the beginning of the 20th century, Christians represented 13 percent of the Middle East population. Today, estimates put these earliest Christian communities at a mere 4 percent.

“I started with nothing in life—not even a pair of socks—and God made me his servant,” said Bouchebel. “The only hope I have is God’s promise that he will not forsake his church, and this is what pushes me to do more and more for others.”

Donald E. Miller is director of strategic initiatives at the University of Southern California’s Center for Religion and Civic Culture and its global project on engaged spirituality, which produced this article with support from the John Templeton Foundation and Templeton Religion Trust.