They were the world’s most famous hostages, yet no one seemed to know what it had taken to bring them home or how they had survived.

Bring Back Our Girls: The Untold Story of the Global Search for Nigeria's Missing Schoolgirls

Harper

432 pages

$22.49

Members of the class of 2014 at Nigeria’s Chibok Government Secondary School for Girls had been just a few weeks from finishing their senior year—just a few weeks from graduating as some of the only educated young women in an impoverished region where most girls never learned to read. It was a Monday. The students had spent the afternoon finishing a three-hour civics test and the evening relaxing on campus, studying in their dorms, or gathering in small circles in the prayer room. Some had been singing cathartic sabon rai, or “reborn soul,” hymns that they had rehearsed since childhood at Chibok’s exultant Sunday services.

Suddenly, a group of militants barged in, bundled nearly 300 girls onto trucks, and sped into the forest. The students became captives of a little-known terrorist group called Boko Haram, which filled its ranks by abducting children. The girls’ parents chased after them on motorbikes and on foot until the trail went cold. For weeks, few people seemed to notice. The schoolgirls looked set to be forgotten, new entries on Nigeria’s long list of stolen youth.

But then, something mysterious happened within the engines that power the world’s attention economy. A small band of Nigerian activists coined a Twitter hashtag calling for the hostages’ immediate release. Through the unpredictable pinball mechanics of social media, that hashtag shot out from West Africa into the realms of Hollywood celebrity on its way to capturing the global imagination. People all over the world began tweeting out a single clarion call: #BringBackOurGirls. Here was a chance to cheer on the crowdsourced liberation of more than 300 innocent victims, terrorized for their determination to learn.

In the weeks that followed, two million Twitter users, with a tap of the screen, repeated the same demand. Ordinary people from every corner of the map made common cause with world-famous actors, recording artists, politicians, and other A listers.

Swiftly, an army of would-be liberators, spies, and glory hunters descended on Nigeria to find the group of schoolgirl hostages that social media had transformed into a central prize in the global war on terror. Satellites spun in space, scanning the forests of a region whose population had barely begun to use the internet. The air power and personnel of seven foreign militaries converged around Chibok, buying information and filling the skies with the menacing hum of drones. Yet none of them rescued a single girl.

Then, two and a half years later, on an overcast day in October 2016, 21 hostages were abruptly released. Another 82 were freed the following May. (More than 100 remained unaccounted for.)

Although widely celebrated, the releases received nowhere near the coverage devoted to the kidnapping and the social media campaign. There was no comment from the Nigerian government on the price it had paid to secure their freedom. With the rescue efforts shrouded in secrecy, the liberated hostages were immediately placed in the custody of Nigeria’s intelligence agency and then moved to a heavily guarded university campus in the country’s northeast. Their experience in captivity appeared to be a state secret.

Holding on to faith

As reporters for The Wall Street Journal, we set out to try to understand the riddle of the hostages whose plight captivated the world in 2014: What had it taken to free them? What were the consequences of that deal? And, perhaps most importantly, how had they survived?

The investigation would take years, ushering us from the frontlines of Nigeria’s insurgency to the Oval Office, from palatial government offices in Geneva to the dusty back streets of Khartoum. As we plunged further into the secret world of drone surveillance and hostage talks, we confronted a leviathan of a story that went beyond what we could have foreseen.

But as we interviewed some 20 of the young women, we discovered something about the beating heart of this story that much of the foreign coverage had missed. We saw clearly how the teenagers’ will to survive was inseparable from their religious convictions. Most of the students were Christians: members of the Church of the Brethren, a mainline Anabaptist denomination whose global missionary service, headquartered in Illinois, had reached into the remote town of Chibok in the 1940s.

These young women had endured three years of captivity, deprivation, and pressure to convert to Boko Haram’s creed by holding onto their friendships and their faith. At the risk of beatings and torture, they whispered prayers together at night, or into cups of water, and memorized the Book of Job from a smuggled Bible. Into secret diaries, they copied Luke 2, because they saw themselves in Mary’s ordeal of giving birth to Jesus. They transcribed paraphrases of psalms in loopy, teenage handwriting: “Oh my God I keep calling by day and You do not answer. And by night. and there is no silence on my part” (22:2).

They came of age in captivity, pressured daily to marry fighters and embrace Boko Haram’s creed in return for better food, shelter, clothing, and soap. By their second year, many were badly malnourished. Months of hunger and vanishing rations had left some of the women unable to stand without help. Sometimes they ate tree bark or the sinewy grass called yakuwa, which their mothers used to weave mats and baskets. There were small seeds between the blades, which they plucked out. Some drank hot water, believing the heat would give them energy. At one point, a classmate killed an ant to eat the crumb of food it was carrying.

Their guards had refused to share meals or even jugs of water—except for washing before prayer. Boko Haram itself, though running low on rations, still promised what little food it had to those who agreed to convert and marry into the sect. More than 100 refused. Many of them had been members of choirs in their church, and all of them knew the words to a hymn from Chibok they sang when their guards were out of earshot: “We, the children of Israel, will not bow.”

Secret diarists

At 24, Naomi Adamu was one of the oldest captives, a student who had prayed and fasted more times than she could count to get through high school. Petite, with a teardrop-shaped face and slender, arched eyebrows she liked to outline with an angled brush, Naomi had struggled for years with chronic health problems that kept her out of school. Younger classmates knew her as Maman Mu, which meant “Our Mother,” or “the Preacher’s Wife,” a subtle tease and a poke at her self-righteous streak. Her favorite singer was a local gospel star, Mama Agnes, whose lyrics called for Christians to keep their faith.

Naomi’s extended family included Christians, Muslims, and converts between the two, but by senior year her mind was made up. She told classmates she planned to marry a pastor. “I’m married to Jesus Christ” went the chorus of a bubbly, syncopated Mama Agnes song that she knew by heart. “And nobody can separate us.”

In the forest, her devotion became a strength. In the earliest minutes of the kidnapping, she and two other students thought to hide a Bible in their clothes. Hours later, when Boko Haram demanded the students turn over their cellphones, she concealed hers, a Nokia handset. When guards distributed full-length mayafis to wear, she secretly wore her blue-and-white checkered school uniform underneath it, holding onto that article of defiance for three years.

As the girls’ captivity ground into its third month, Naomi found herself sitting next to a girl she had only vaguely known at school, one of its star pupils. Lydia John, who spoke the best English at the school, had arrived in Chibok at the start of her senior year, fleeing her hometown of Banki, near the border with Cameroon, after an attack by Boko Haram. In her new school, she immediately rose to the top of the class.

Lydia felt certain that when she graduated she would win a place at a university and had already begun to dress the part, wearing Western skirts she found more fashionable than the local wrappers her mother bought. She was tall and elegant and seemed to wear her clothes more like a girl from the city than a high school senior from small-town Chibok.

But Lydia, more than most, was showing the strains of captivity. She was struggling to sleep, missing meals, and seemingly lost in the haze of her own fears. When she spoke, she talked about escaping, whispering about elaborate plans she was concocting in her mind. Most of her school friends were just trying to hold on. “You’re thinking too much,” several told her.

One day after lessons, Lydia said she wanted to tell Naomi a secret. She checked that nobody was looking, then carefully opened her blue exercise book and began to slowly flick through the pages. Naomi watched the blanks toward the front give way to pages covered in wide-looped handwritten English. She pulled the notebook from Lydia’s hands and began to read. It was a record of their ordeal, starting from the night of April 14. Lydia was writing a diary.

It began: “First of all on 14 April 2014 on Monday. 11 o’clock. We heard the sound of gun and then some started phoning their parents, brothers, sisters, uncles. And we started praying …”

“You must write one too,” she said to Naomi.

Lydia’s diary habit had originated when Malam Ahmed, the girls’ chief guard, distributed notebooks into which the girls were meant to write Qur’anic verse. (Among Muslims in Northern Nigeria, the title Malam denotes a respected teacher of the Qu’ran.) An elderly theologian who carried a switch in his left hand, the Malam had told the girls that memorizing his lessons would help save “daughters of infidels” from the arna, the pagans. “There will be tests!” he had warned.

Soon after Lydia unveiled her secret to Naomi, a small club of secret diarists began huddling together in the afternoon shade. They shared paper and pens and ideas about how to tell their story. Naomi would sometimes write and sometimes dictate her reflections to Lydia, who shielded them under pages of halfhearted notes they took in Malam Ahmed’s class. Each diary described the same events from a slightly different perspective that evolved as the schoolmates read one another’s work.

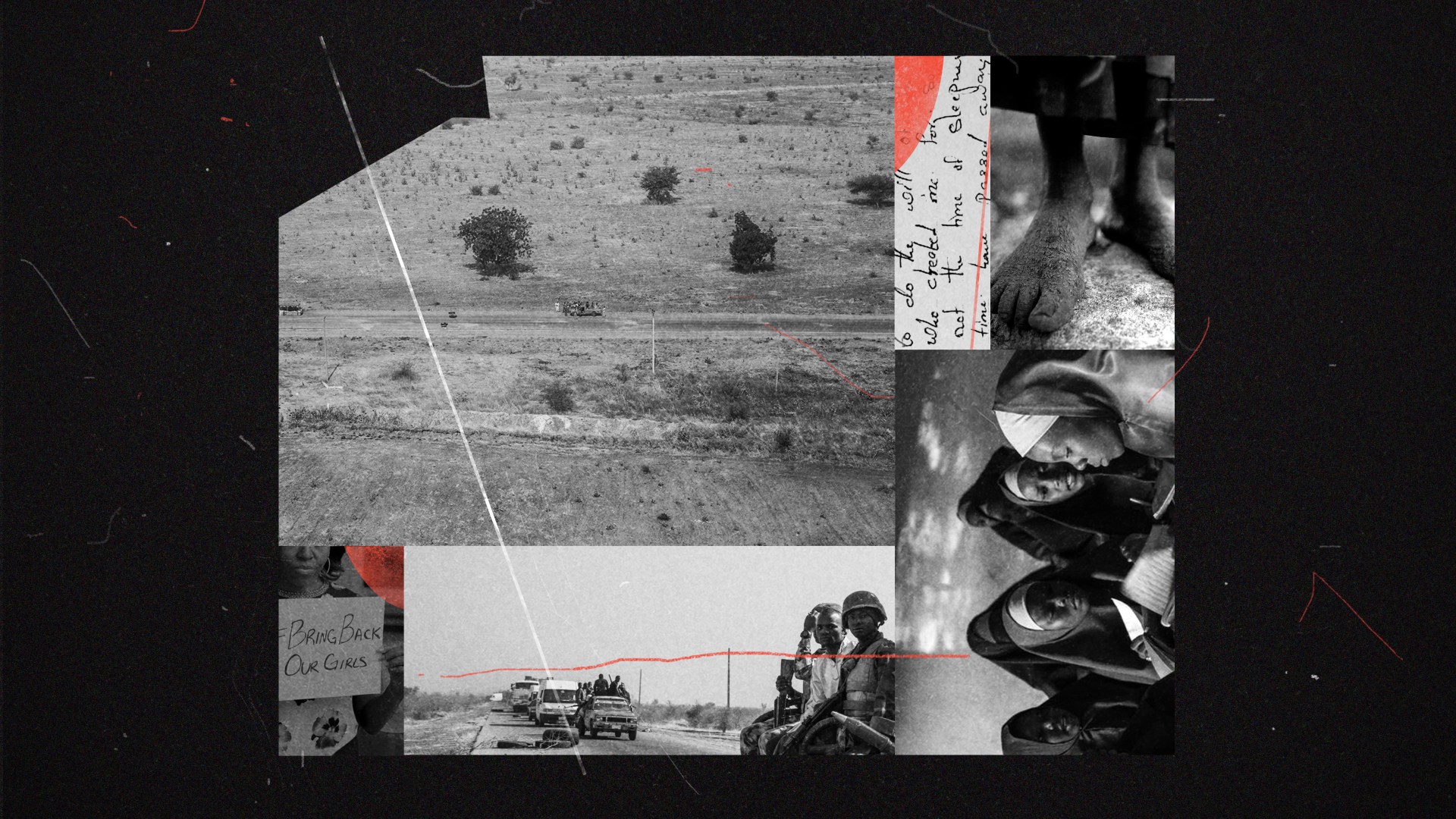

Illustration by Mallory Rentsch / Source Images: Courtesy of HarperCollins

Illustration by Mallory Rentsch / Source Images: Courtesy of HarperCollinsAt first, they wrote about the kidnapping: fragmented recollections from their journey into the forest and the terror of their first weeks in captivity. As the weeks dragged on, however, other material went into the pages. They copied passages from a small Bible one of the teenagers had smuggled. One schoolmate would ask for permission to go to the bathroom so she could find a bush to crouch behind and copy the verses.

The girls had discovered a survival mechanism many prisoners of war would recognize. Nelson Mandela wrote his autobiography at night on scraps of paper he had buried in a vegetable garden by day, and dozens of Holocaust victims kept similar diaries. Like other captives, the teenagers were keeping a record of injustice that they believed would ultimately come to light. “We were hoping that we would eventually be released,” Naomi said. “We wanted the world to see what we saw.”

Praying to escape

The diaries were a subtle form of rebellion that would soon progress to more daring acts of mutiny. One morning at the beginning of Ramadan, before the dawn prayers, Naomi and her classmates noticed Malam Ahmed speaking animatedly with his guards, several of whom hurried off to board motorbikes that screeched into the bush. The Malam’s daily head count had come up short. A pair of girls had made a run for it during the night. The news caused ripples of hushed excitement.

It was time for prayers, and the Malam organized the girls into rows. Naomi bowed her head in front, but as she pressed her face to the floor, she was thinking about her classmates and praying they could make it out. The Malam had always warned the girls that mounting an escape was futile. Boko Haram had spotters and lookouts posted all around their camp, and even if someone managed to make it to the edge of the forest, that person would be shot.

The plotting ended with a commotion of gunshots fired into the air and screams announcing that the two breakaways had returned. Their hands were tied with rope, and they were shoved forward by an escort of more than a dozen guards. The girls’ faces and garments were caked in dirt. Malam Ahmed called for all the hostages to gather and watch the runaways’ punishment. He ordered the girls to kneel and then gestured to a tall, scowling militant who approached them carrying a large tamarind branch.

His name was Abu Walad, and he brought the gnarled branch down hard across their shoulders and their backs. They screamed and buckled, yelling at him to stop. Naomi and the hostages watched, wincing, some sobbing or looking at the ground. “Do not look away!” Malam Ahmed said. Abu Walad beat them 20 times each, counting the blows, their bodies splayed out on the ground.

Another guard arrived with an assault rifle. He hauled the escapees back onto their knees, placed the rifle next to one of their heads, and screamed, “Let me open your ears.” Then he fired it into the air. “You will listen,” he said.

Malam Ahmed addressed the crowd to issue a final warning: “Anyone who tries to flee will be beheaded.”

Illustration by Mallory Rentsch / Source Images: Courtesy of HarperCollins

Illustration by Mallory Rentsch / Source Images: Courtesy of HarperCollinsNo longer afraid

In time, however, Boko Haram’s authority over the Chibok girls began to wane. As it did, the young women began to sing. The main material they drew on was the music of Mama Agnes. As they performed the vocals, they would strive to remember the bouncy Casio keyboard beat and brisk rhythms that would have poured from a speaker at a wedding or church service in Chibok. Mama Agnes had a voice like a flute, which fluttered along at a heavenly register, like a record playing at the wrong speed. Naomi couldn’t hit those notes, but she could help her friends reach for them.

An insurrection began to brew among the captives, and singing was its most provocative expression. At prayer times or whenever guards were dozing or distracted, clusters of hostages would sing through cupped hands while lying on the ground to muffle the sound. Other times they gathered in a tight circle, heads bowed toward each other, singing into the dirt, their voices bouncing back. One evening, when the guards ambled off for Maghrib prayers, dozens of girls began singing together in hushed chorus.

“Nebuchadnezzar is the king of Babylon,” they sang. “Big king of Babylon.” These were the opening lines to a hymn about Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego.

One day, Naomi and Lydia wrote down the lyrics to “Shake,” a pulsating Nigerian dance-floor hit that had been on heavy rotation in the months before their abduction. They laughed as they read the verses and chorus aloud, bobbing their heads in a silent rhythm.

Mr Flavour on the Microphone

baby so fine

baby so fresh

Eventually, word of the girls’ indiscipline reached Malam Ahmed. The girls were singing, he learned, and were hiding a Bible. He was furious. His guards arrived, a mass of men descending on them all at once, shouting orders and demanding to search the area. The girls stood to the side while the men rifled through the piled-up clothes and kitchen utensils they kept under a tree. The militants confiscated medicine, mainly basic painkillers the girls had been hiding. They found a cellphone. But the girls had already buried their diaries and a Bible, marking the spot with a stone.

“We were no longer afraid,” Naomi told us.

It wasn’t until May 2017 that she and 81 of her classmates were ordered to march to the side of a dirt road, where a row of white Red Cross Toyota Land Cruisers were parked. One after the next, the young women were invited to cross the road by a lawyer, who had been working with the Swiss Foreign Affairs ministry to help negotiate their release. The cars rumbled off, and as the schoolmates cracked open juice boxes, the men who’d held them hostage for three years became small figures on the horizon. The journey had barely begun when the passengers broke into a song from Chibok, loud enough that the entire convoy could hear and join in. Their voices arched and lingered over the a in happy, reaching for a note at the top of the melody.

Today is a happy day!

Everybody shake your body, thank God! Today is a happy day.

Years later, Naomi began to recount these anecdotes to us, recalling a story of courage in the face of horrors that sounded fantastical in their depravity. Nevertheless, after many hours of interviews with the young women held in captivity, it became clear that her account often understated the schoolgirls’ bravery. Naomi and her friends had no reason to believe they would survive their ordeal and every expectation that each challenge to their captors’ worldview would result in physical and mental punishment. They stuck to their principles all the same, staging a rebellion that signaled their determination to persevere.

“We stood our ground,” as Naomi later told us.

The language of resistance

For us as reporters, the schoolgirls’ testimony upended years of faulty premises about Nigeria. In our decade of covering the country, which is almost evenly divided between Christians and Muslims, it had been easy to view religious identity as a source of conflict rather than a strength. Nearly 40,000 people have died in Boko Haram’s war with the state, and 2.5 million people are homeless. Thousands more have died in Christian-Muslim conflicts in the country’s Middle Belt, where fights over farmland and jobs have often melded into religious pogroms. At times it could be easy, as a Westerner, to adopt the facile hope that Nigeria’s problems might be resolved by gradually secularizing its more than 210 million people.

Yet we found a different perspective in a group of young women who had faced unimaginable hardship and survived. Their faith provided twin anchors of identity and hope during a period when their captors were trying to erase both. Repeatedly they were told their parents were dead, their places of worship were torched, and their community was now flying Boko Haram’s black-and-white flag. But faith became the language of their resistance. Their regular fasts transfigured hunger into a source of strength, as they took turns renouncing food for a few days to create a spiritual energy they believed would help free them.

On days when their resolve was weak and they had every incentive to give in, Naomi and her classmates leaned into their faith as a source of strength: “Just be faithful,” they would tell one another. Their surreptitiously scribbled Bible passages and whispered hymns were not only manifestations of belief but also a way to remember home, family, and who they were before their abduction. Unbeknown to the hostages, their mothers were doing the same thing back in Chibok: gathering to pray and fast to seek strength.

From the moment we met Naomi and began to hear her incredible story, she explained her survival through the language of faith and showed us the letters she wrote to her family while in captivity. “We put our fate in the hands of God,” said one pencil-sketched letter, hidden for three years before being smuggled to freedom. “Pray that God should touch the heart of Boko Haram terrorists so we can be set free.”

Joe Parkinson and Drew Hinshaw have extensive experience covering West Africa as reporters for The Wall Street Journal. They are the authors of Bring Back Our Girls: The Untold Story of the Global Search for Nigeria’s Missing Schoolgirls, from which parts of this article have been adapted.