“Therefore I conclude that we should not cause extra difficulty for those among the Gentiles who are turning to God.” (Acts 15:19, NET)

It has never been more complicated to be a pastor than it is right now. At least that’s how it often seems. As racial tensions and culture clashes have dominated the headlines in our nation, too often those unwanted guests have decided to attend our churches as well. How do we navigate our ministries to the safe harbors of peace and unity while still fulfilling our prophetic call to proclaim the truth of the gospel that challenges our tendency to elevate our norms over others? And how can Scripture equip us to address today’s racial and ethnic tensions?

In the Acts of the Apostles, Luke highlights one of the greatest threats the early church faced: ethnocentrism and cultural pride within the fellowship of believers. As the gospel spread beyond the initial band of Jesus’ Jewish followers across geographic and cultural boundaries, these impulses threatened to pull the adolescent church apart. Eventually the controversy led to the Jerusalem Council described in Acts 15.

“The key question, then, in Acts 15 is not ‘Do these people have to do circumcision as a good work in order to get justified?’ ” N. T. Wright observes. “It’s …‘Do you have to become ethnically Jewish in order to belong to the family of Abraham, the people of promise?’ ” The way early church leaders dealt with this question in the Jerusalem Council provides a powerful model for how we can respond to racial division in our churches and communities today.

The situation

At his ascension, Jesus told his followers, “You will receive power when the Holy Spirit comes on you; and you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth” (Acts 1:8). Jesus’ call to his followers foreshadows the structure of the Book of Acts. Luke details the spread of the gospel in Jerusalem (chapters 1–7), then expands the narrative to Judea and Samaria (8–12), and finally describes the church’s reach to the ends of the earth (13–28). But this Spirit-driven growth into new regions also provoked an existential crisis right at the very beginning of the church.

By this point in history, many Jews felt their ethnicity and culture gave them not only a source of righteousness as God’s chosen people but also an inherent superiority over the Gentiles. Many even recited a daily prayer: “Blessed are You, Eternal our God, who has not made me a gentile.” Even those who followed Christ could not fathom that God would save Gentiles without somehow making them “Jewish” religiously and culturally.

This problem was so pronounced that God orchestrated a series of supernatural occurrences to reveal his will to Peter that he should not refuse to eat with Cornelius, a Gentile, who would be saved, receive the Holy Spirit, and be baptized during Peter’s visit (Acts 10). Peter certainly had religious concerns about being unclean and carefully following the law, but there was more to his initial strong hesitation: a cultural blind spot that caused him to look down on Gentiles. Peter shared this lesson with Cornelius in Acts 10:28: “God has shown me that I should not call anyone impure or unclean.” Peter would continue to struggle with this lesson even after receiving the miraculous vision (Gal. 2:11–12).

While Peter was working through his issues, God used the apostle Paul to help the church fulfill its calling. “This man is my chosen instrument to proclaim my name to the Gentiles,” God said of Paul (Acts 9:15), and after his conversion, Paul grew a following of Gentile believers that garnered a lot of notice. Controversy emerged as some church leaders objected to Paul’s support of Gentiles joining the church with their Gentile culture still intact.

This is what sets the scene for the Jerusalem Council, and the stakes could not be higher. Either Gentiles should be encouraged to follow Jesus without rejecting their cultural identity and customs, or the church would have to insist that Gentiles convert to Judaism and cease expressing their unique ethnic and cultural identities in order to follow Christ. The religious and cultural implications were enormous for both gospel contextualization and discipleship.

The proceedings of the Jerusalem Council (Acts 15) are both structurally and theologically at the center of the Book of Acts. The council’s ruling would address the false theological claims that sought to add works of the law to the grace of the gospel. But the social implications of this teaching, which are subtle and often overlooked, would also be of great importance. We find in the Jerusalem Council a defining moment for the growing church—to be witnesses of either cultural supremacy or contextualization.

A persisting problem

The temptations of cultural and ethnic superiority experienced by believers in Acts have continued to be a struggle for the church throughout history and up to today. Whenever there’s a dominant culture, the potential for cultural pride increases. In America’s history, for example, Eurocentric assumptions have prompted various preachers to endorse false teachings like the curse of Ham, Manifest Destiny, and racial segregation, insisting God ordained the subjugation of nonwhite peoples, whether Black, indigenous, Latino, or Asian. This legacy has wounded the church’s reputation, inflicted harm on countless people, and caused deep divisions that still linger today.

Groundbreaking British missionary Hudson Taylor modeled a better way in the 1800s when he chose to embrace Chinese culture instead of continuing the prevailing practice of baptizing the Chinese not just in Jesus’ name but also essentially in the name of Victorian-era values and aesthetics. Like at the Jerusalem Council, Taylor denounced the obstacles created when we don’t see our own cultural blinders. In a letter to aspiring missionaries, he wrote:

The foreign appearance of the chapels, and indeed, the foreign air given to everything connected with religion, have very largely hindered the rapid dissemination of the truth among the Chinese. But why need such a foreign aspect be given to Christianity? The word of God does not require it; nor I conceive would reason justify it. It is not their denationalization but their Christianization that we seek. (emphasis added)

Today, we too can hinder our communication of the gospel and contribute to cultural division—often unintentionally. For example, we may tend to quote only church leaders who look like us, or we may worship with songs that essentially ignore the diversity of the community we aspire to reach or be. Fortunately, in Acts 15 we find not only the source of the problems but also the solution.

The solution

In Acts 15:7 (NET), Luke points out that that “there had been much debate” but nothing close to a resolution on the question of whether Gentile believers must become culturally Jewish (via circumcision and adherence to other aspects of the law). Then Peter shared how God showed him through Cornelius’s conversion that “he did not discriminate between us and them” (v. 9, NIV). Peter even confronted hypocrisy by acknowledging that these Jewish believers were trying to hold Gentile believers to a standard higher than either they or their own ancestors could fully live up to (v. 10).

The assembly also listened as Paul and Barnabas testified about witnessing miraculous conversions among the Gentiles. As a result of these testimonies, the apostle James, serving in a presiding role, said, “I conclude that we should not cause extra difficulty for those among the Gentiles who are turning to God” (v. 19, NET). James issued a statement that was adopted by the council and had enormous implications for the future of the church: The Gentiles would not need to reject their culture and ethnicity to follow God. The letter from the Jerusalem Council served as a remedy that helped make the church whole.

Our model today

While the Jewish-Gentile controversy has long been settled, Acts 15 provides us with a crucial theological framework for addressing all forms of ethnic and cultural superiority. What can we learn from the actions of the Jerusalem Council when it comes to racial tension or issues of prejudice and ethnocentrism in our churches and communities?

Address the issue. The apostles confronted the controversy head-on as both a theological and ecclesial matter. They didn’t dismiss it for fear of upsetting people. They did not shrug it off as an issue unimportant to the gospel. They dealt with it directly because they saw that the ability to be the church was at stake. Though it may be uncomfortable, we too are charged with addressing the issue. In our own local contexts, what are some ways we may need to directly address the issue of cultural pride?

Acknowledge power dynamics. Luke starts Acts 15 with the fact that “certain people came down from Judea” (v. 1). Judea, the province that included Jerusalem, was the epicenter of the church’s influence. Jewish believers were the dominant group in the church at the time, both numerically and culturally. As cultural insiders, it would have been easy for them to more firmly establish their cultural preferences and values as the norm. In their context, keeping kosher, observing the high holy days, and circumcising male babies were what godly families did.

But Luke reveals the wisdom of these leaders from Judea as they chose to seek God through organizing a council to hear the stories of others. Peter, who had already reported the story of Cornelius to believers in Jerusalem (Acts 11), testified to Gentiles receiving the Holy Spirit. Paul and Barnabas also spoke on behalf of the many Gentiles they’d led to faith in Christ. Peter, Paul, and Barnabas all leveraged their influence for those who didn’t have it.

Power dynamics exist in every group. Even multicultural and multiethnic congregations often still have a dominant culture in practice. Becoming more aware of how culture and ethnicity are influencing the experience of people in our churches can help us avoid blind spots. Using that knowledge—like Peter, Paul, and Barnabas did—can enable our churches to be as inclusive as the gospel message is. In humility, we can ask ourselves, “What cultural power dynamics are at play in our own ministry contexts?”

Listen. Only after listening to the accounts of Peter (vv. 7–11) and of Paul and Barnabas (v. 12) did the council make progress (vv. 13–21). It wasn’t the theological debate—as important as that is—that generated progress. It was the council’s willingness to listen to the stories of those whose life experiences were different from their own.

We must learn to listen well to discover how we, too, might be blinded by our own ethnocentrism. There’s a reason why most of the Bible is narrative! God has designed our minds to connect stories with deep meaning. When we’re able to combine facts with stories, it helps us get past our cultural blinders. Whose stories might we need to listen to in our local contexts to gain understanding and insight?

Contextualize intentionally. The Jerusalem Council made what was an extremely provocative ruling at that time—and it’s been so influential that we can miss its seismic significance. Their judgment that the Gentiles need not follow the Mosaic Law or Jewish customs launched the church into embracing its multiethnic, multicultural calling.

Millions of believers haven’t thought about observing dietary laws or circumcision as a means for salvation ever since the council’s decision.But it’s important to note that this wasn’t simply what the Gentiles didn’t have to do. It was also a nod to what they could contribute.

It’s no coincidence that Luke later records Paul, at Mars Hill, quoting Greek and Cretan poets in his presentation of the gospel (17:28). The Jerusalem Council’s ruling empowered him to contextualize the gospel in ways that previously would have been looked upon with suspicion.

It’s a false dichotomy for people to try to choose between their culture or Christ, because Christ intends to be Lord over every culture. Today, that might look like hiring a bilingual worship leader in an increasingly Hispanic neighborhood or intentionally recognizing the contributions of Black Christians during February. That’s not cultural relativism—that’s intentional contextualization. How might we need to contextualize the gospel to reach people from a different culture?

Invest. The Jerusalem Council invested their best leaders and resources to make sure the Gentiles received the gospel and were empowered to live it out. By sending missionaries out to teach and preach to the Gentiles, they spent money, time, and influence for the benefit of those who weren’t “in the room.” In doing so, they ensured the survival of a church. Two millennia later, the church today is primarily led by and made up of Gentiles.

It takes an investment to raise up leaders from different cultural and ethnic contexts. If we care about the future of the church, we should follow the Acts 15 approach to invest in the church’s future. How might our churches invest in breaking down cultural barriers?

Contend for the gospel

The intricacies of ministering in today’s diverse and culturally complex society can’t be overstated. It’s challenging—and yet so is the work of helping people be conformed into the image of Christ. To be the church that truly lives out the Great Commission and Jesus’ call to be his witnesses (Matt. 28:18–20; Acts 1:8), we need to contend, like the Jerusalem Council did, for the culturally contextualized expression of the gospel. We must see the issue of cultural pride as a gospel issue, like they did. We can acknowledge the power dynamics of culture and ethnicity like they did. Listen like they did. And contextualize and invest like they did.

As a pastor in New York City, I am faced with the weekly challenge of engaging a congregation of vast ethnic and cultural diversity. Recently, I was preparing a message as part of a series on the Book of Esther. I saw powerful parallels between the cultural pride and ethnocentrism of Persia and our own society, but I felt convicted that I shouldn’t just use examples from my own African American cultural context for every sermon. So I reached out to some Asian American friends to ask for help and to learn from their experiences. They shared how Christians in the #StopAsianHate movement have provided a powerful example for challenging ethnocentrism.

After I included this example in my sermon, the feedback I received from those who felt seen and heard was priceless. Because I worked to break down my tendency to center my own cultural paradigm, I was left in awe of how contextualization reveals the glory of Christ through the unique lens of his church in our nation and around the world. When we patiently and consistently apply the lessons of the Jerusalem Council, we will experience similar results: a church that looks more and more like the world we are called to reach.

Rasool Berry serves as a teaching pastor at The Bridge Church in Brooklyn, New York. He is also the host of the podcast Where Ya From?

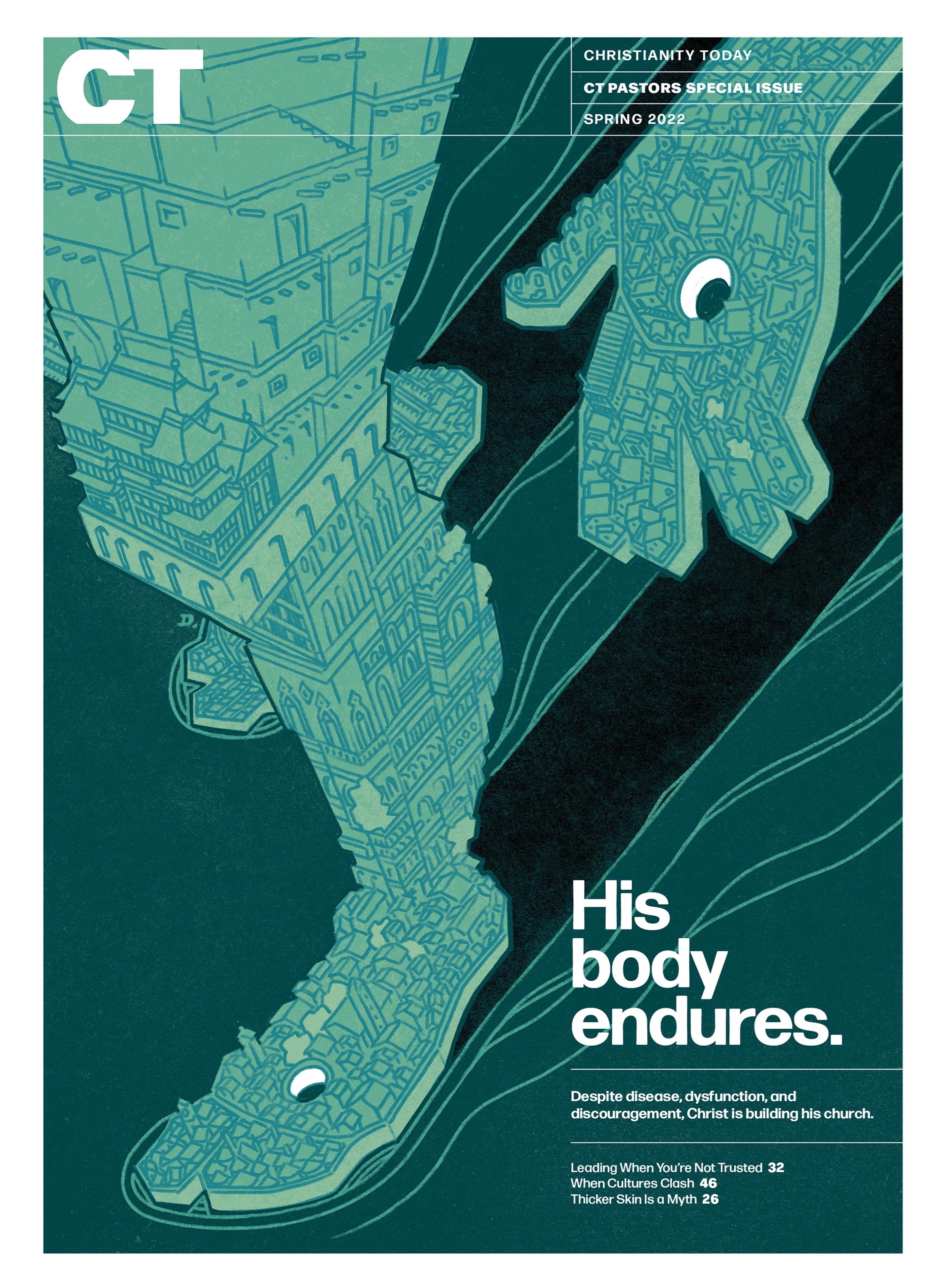

This article is part of our spring CT Pastors issue exploring church health. You can find the full issue here.