Recently, there have been discussions about the core identity of humankind—whether we are first and foremost sinners in need of a Savior, or whether God has created us with a nature that is fundamentally good. This is a deeply theological issue with implications for nearly every aspect of our lives and society at large.

Who are we? Why are we here? What does it mean to be human? These are questions that virtually every human society has asked and answered through origin stories—which are religious or cultural narratives that speak to the purpose and destiny of humanity.

I explored many different origin stories from around the world while creating a video series called “Storytelling and the Human Condition” for The Teaching Company and Wondrium (formerly The Great Courses). And even though I was raised in an evangelical Christian home, I was struck by how much I took for granted in the Judeo-Christian anthropology when I compared it to others.

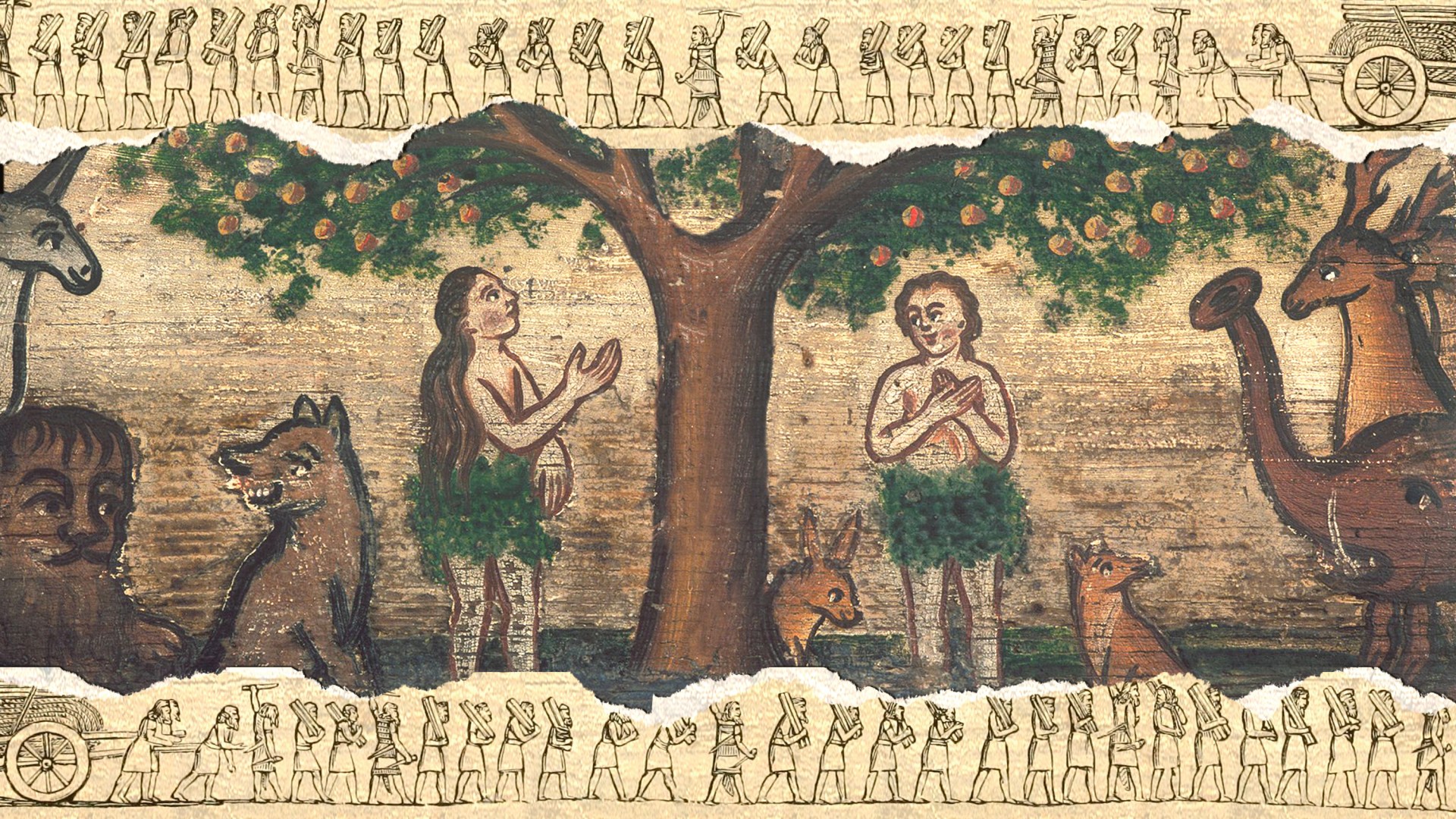

In the Judeo-Christian worldview, the origin story of humankind is defined by the imago Dei: the notion that God created human beings in his image. And when I compared the creation narrative in Genesis to other ancient origin stories from the Mesopotamian region, this concept hit me in a new way.

Genesis reveals important information about the character of the Judeo-Christian God. There is a single Creator who acts upon the world with intention and brings order out of chaos. There is a purpose to it all. It is all done in a peaceful environment: The phrase “Let there be” is sufficient to bring whole new creations into being.

After the creation of the cosmos, earth, and animals, God creates Adam and Eve—suggesting that humankind is the pinnacle of the created world. Human beings bear the imprint of the divine, as we share in the nature of the God who created us. The imago Dei means that we have dignity as well as a responsibility to steward the rest of the created world.

In contrast, let’s consider what is often considered to be the world’s oldest creation story—the Enuma Elish from ancient Babylon around 1100 B.C. This violent narrative may seem strange to us now, but it reveals how the ancient Babylonian civilization understood how the world, the gods, and human beings came to be.

Two primordial beings—Apsu and Tiamat—exist at the beginning of time. They give birth to other gods. When their children act out, some rather gory intergenerational warfare begins.

After great tumult, Marduk, the son of Apsu and Tiamat, creates the heavens with one half of his mother’s body, and the Earth with the other half. Marduk makes his fellow gods stewards over the heavens, the air, and the water, and sets the planets and time itself in motion.

The rest of the gods—still bitter toward the older generation of gods—demand more revenge, so Marduk kills his stepfather, Kingu, and from his blood, Marduk creates humanity.

Marduk states his purpose in creating mankind: “I shall bring into being a lowly primitive creature … so that the gods may have rest” (emphasis added).

The cosmos is now set. Marduk is the supreme ruler over the universe, including the other gods and humanity. Human beings were created as an afterthought—only after the other gods complained about their labor and yearned for more revenge—and humanity’s purpose of existence is to “set the gods free” from the labors of their daily existence.

The Genesis narrative and the Enuma Elish share some similarities.

For example, both stories draw from the idea that while humanity partakes in the nature of the divine in some way. In Genesis, man is created in God’s image, and God breathes life into Adam. In the Enuma Elish, humanity emerges from a god’s blood. Still, humanity is still distinct from God in both stories.

Relatedly, both Genesis and the Enuma Elish claim that humanity was created for work. God commanded Adam and Eve to cultivate the earth, and to be stewards over it. In the Babylonian story, mankind was intended to work in service to the gods for all of time.

But there is a difference between the stewardship of Genesis and the servitude of the Enuma Elish. In Genesis, we weren’t merely created to work. We, and creation in general, have a non-utilitarian purpose as well: to delight God, and to delight in him.

The refrain that comes after each act of creation— “And God saw that it was good”—shows that God took pleasure in his created world. A superlative is added to this statement after human beings are created, when “God saw all that he had made, and it was very good” (Gen. 1:31, emphasis added).

Genesis tells us that there is beauty and abundance to be found and enjoyed in the world he created for us to inhabit. Beauty and enjoyment are non-utilitarian. We have work to do here on Earth, but enjoying our life in the fulfillment of our duties affirms the way that God created us to be. There is also an order, a design, and a purpose to the world—of which we were created to take part.

In Genesis, human beings are unique among creation. We weren’t created as an afterthought amid a cosmic intergenerational warfare and out of a murdered god’s blood to free other gods from labor, as was the case in the Enuma Elish. In the Babylonian narrative, there was no created “first man”—there was no Adam—but instead humanity was created anonymous and en masse.

The New Testament also tells us that human beings were created to lead lives of joy and fullness. As Jesus says in second half of John 10:10, “I have come that they might have life, and that they might have it more abundantly” (NKJV).

In the Judeo-Christian story, no other creature was created in God’s image. Humans are distinctively and intrinsically valuable. This tradition has been integral in developing the concepts of human dignity and human rights which we often take for granted in our modern world today.

As secular classicist Tom Holland argues in his recent book, Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World, universal human rights or a concept of personhood were completely foreign to the pagan, Greco-Roman world. It was Christianity, and the imago Dei, that forged and built our ethic of basic respect for other human beings today.

The idea that all human beings have equal worth in God’s eyes is a historic anomaly. Most of human history has rejected this idea—that only one’s tribe and one’s family mattered. Everyone else was less valuable, or less than human—especially one’s enemies.

The stories we tell reflect and shape how we see the world and our place in it. The narratives we accept about our origins—along with what we believe about God and humankind’s relationship to God—invariably colors how we view our role and purpose in the world. Exploring worldviews that differ from ours allows us to see what we take for granted: They clarify, and help us better appreciate, our own stories.

Comparing the Babylonian origin story to the Genesis creation narrative renews my gratitude that I’m not merely an inglorious servant to the divine, my fate subject to the whim of their caprice. Instead, I serve a just and benevolent God who is fundamentally affectionate toward his creation—and especially toward humans, whom he created to delight in and to bear his own image.

We become more fully human, and more truly ourselves, when we partake in and reflect his image by creating and engaging in the world around us—beautifying and ennobling in our work as “little creators”—including when we tell and retell meaningful stories.

Alexandra Hudson is the founder of Civic Renaissance, a former Novak Journalism Fellow and the creator of a new series with The Teaching Company, called Storytelling and the Human Condition. Her book, The Soul of Civility: Timeless Principles to Heal Society and Ourselves, is forthcoming from St. Martin’s Press.