Wayne Coleman, a teenage Pentecostal preacher who became a professional wrestler and took the name of the world’s most famous evangelist to perform as Superstar Billy Graham, died on Wednesday at age 79.

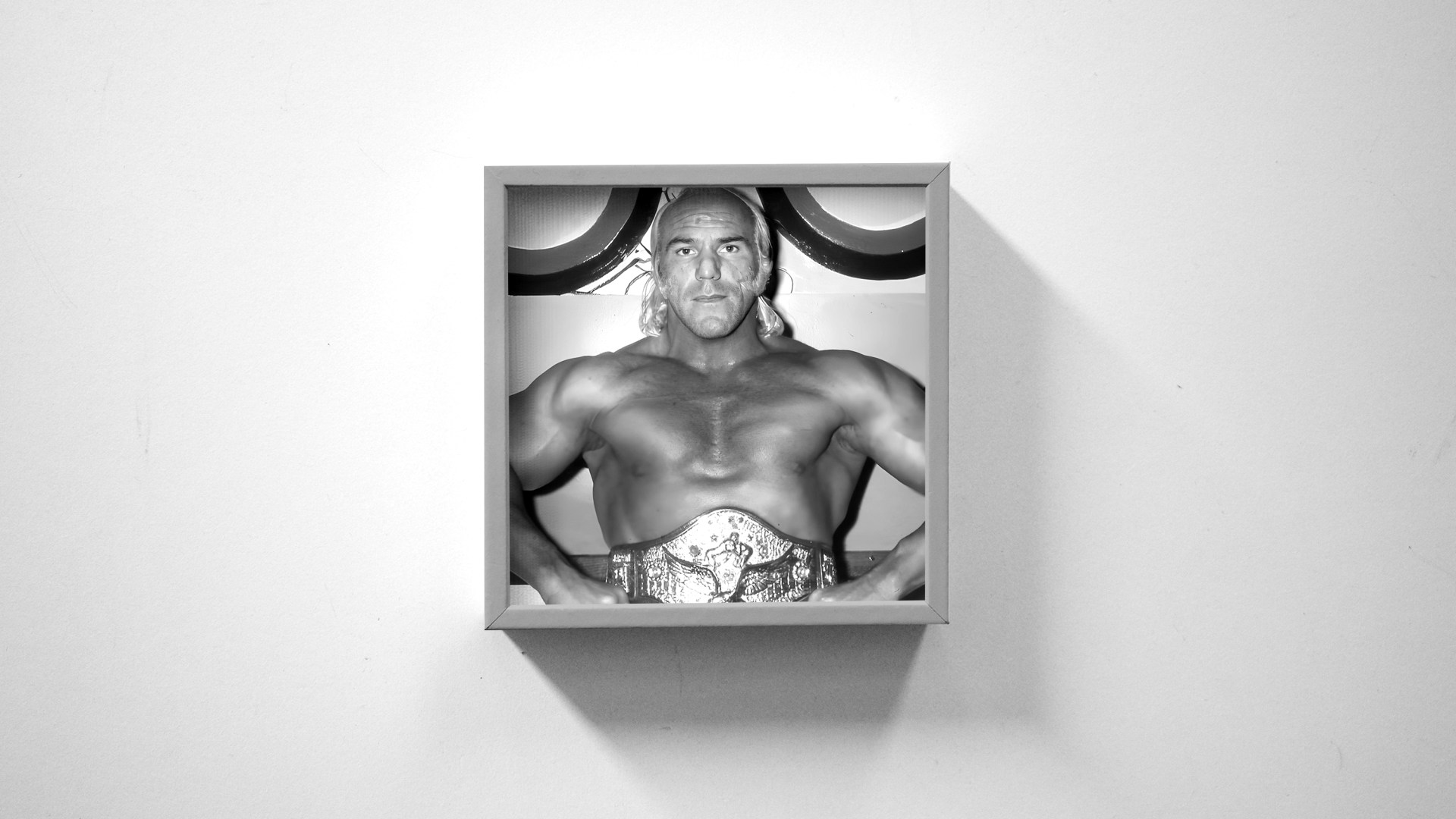

Coleman was a charming, flamboyant, and braggadocious performer who brought bodybuilding into wrestling and influenced some of the biggest stars, including Jesse “The Body” Ventura, the Iron Sheik, “Stone Cold” Steve Austin, Ric Flair, and Hulk Hogan, who borrowed Superstar Billy Graham’s speech and style.

“This is the most copied guy in the business,” the wrestler Triple H once said. “He was the guy who broke the wall in terms of where you could go with entertainment. He paved the road for Hulkamania. He paved the road for all of us.”

For most of Coleman’s career, he played a heel, as professional wrestlers call the villain. Crowds across the country would boo and hiss as he flexed, posed, and boasted that he was “the reflection of perfection,” “the sensation of the nation” and “the number one creation.” But Coleman desperately wanted to become the babyface, or hero. He struggled to get World Wide Wrestling Federation (WWWF) chairman Vince McMahon to script him the redemptive, transformational narrative arc he longed for. He rose to the top of the WWWF, defeating champion Bruno Sammartino in 1977, only to learn the coming storyline would treat him as a transitional figure to be defeated by the next babyface, Bob Backlund. He was defeated in Madison Square Garden in 1978.

Coleman disappeared from wrestling, mounted an ill-fated comeback, and then quit for good. He suffered extensive physical pain from decades of steroids abuse. He returned to ministry in his later years, joining a Christian athletes organization to share his testimony with young people and prison inmates.

“I never fell away from my faith and belief in God and Christ, but I certainly fell away from living the testimony,” Coleman said in 1997. “If I had to do it all over again, I wouldn’t have gone into wrestling. I would have stayed in the ministry.”

Coleman was born in Paradise Valley, Arizona, on June 7, 1943. He was the fourth child of Juanita Bingaman Coleman, who had moved from Arkansas to Arizona escape an overbearing father. Her husband and the father of three of her children, Eldridge John Coleman, followed and found work erecting power poles for the electric company before he developed multiple sclerosis. The elder Coleman drank too much and beat and berated his young son, according to family members. The younger Coleman grew up mean and wild and spent much of his teenage years fighting other kids on the street.

“I went out with trouble on my shoulder,” he wrote in his coauthored autobiography, “always looking for a fight.”

Coleman found refuge in competitive bodybuilding, which was becoming widely popular in the United States at the time. He won the West Coast Teenage Mr. America competition in 1961 and got his picture in a popular bodybuilding magazine.

That prompted a Pentecostal woman named Beverly Swink Welch to show up at his front door. She said someone she had met through the Full Gospel Business Fellowship had seen Coleman’s photo in the magazine and felt compelled to ask her to tell him about Jesus. (“I believe in God,” Welch recalled, “but this was freaking me out.”) She tracked Coleman down and invited him to church with her family.

Coleman declined, but a short time later he stumbled across a revival tent in Phoenix with a big sign that read Ye Must Be Born Again. He went inside and heard the fundamentalist Baptist John R. Rice preaching on the doctrine of eternal salvation. Once you were saved by Jesus, Rice said, there was nothing you could do to separate yourself from the grace of God. Even if you were “in the arms of a harlot with heroin in your veins” when Christ returned on a cloud of glory, Rice preached, “you will still make the Rapture.”

When it came time for the altar call, the fundamentalist looked directly at the gawking young bodybuilder and said, “Come on, son. … It’s your turn to be saved.”

Coleman called Welch afterward and said he would like to go to church after all. He joined the Assemblies of God and soon started traveling to give his testimony. Evangelist Jerry Russell took Coleman under his wing and started mentoring him. He taught Coleman everything from how to tell his story, how to shave his armpits to reduce the sweat smell while preaching, how to make a big entrance at the start of the night, and how to get someone to respond to the message.

It was “pure show business,” Coleman said, but that didn’t make him cynical. He was, in fact, enthralled.

In his autobiography, Coleman remembered riding with Russell through the countryside in a powder blue Cadillac and thinking he had found his calling.

“Here I was, man,” he wrote. “I was going to be a Holy Ghost preacher.”

He struggled, though, with sexual temptation. He frequently had sex with women after evangelistic events, he said, then felt bad about it, then did it again in the next town.

After a while, he started to see the secret lives of the ministers around him too, and though he didn’t lose his faith in Jesus or the power of the Holy Spirit, he was deeply confused and conflicted about evangelism and revivals. One minister confessed to Coleman that he was homosexual. Another snuck off to strip clubs. Russell was accused of sexually assaulting a child and would eventually spend the end of his life in prison.

Coleman drifted away from evangelism. He got a job as a bouncer in a Phoenix bar and then tried out for professional football. When that didn’t work out, he was invited to join some Canadian players in their off-season job in Calgary: wrestling.

He was hired by Stu Hart—the “mentor of mayhem” and head of promotion company Stampede Wrestling—and learned the basics of the craft, especially how to “get over,” performing the moves in a way that wouldn’t hurt other wrestlers but would convince the audiences they had gotten their money’s worth. He found out he was good at it. He could always get a reaction from the crowd.

Coleman was then recruited by wrestling legend Jerry Graham to be part of his wrestling “family.” To join, Coleman had to change his name, and he decided to adopt the moniker of the famous evangelist.

“The reverend was one of my heroes,” he said.

If audiences found it a bit incongruous to see a heel named after the most respected religious figure in the country, they just chalked it up to the way wrestling was. In the early 1970s, Coleman added “Superstar,” inspired by the popularity of the rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar. He was always finding new ways to provoke a crowd.

“Man, he was crazy,” said Arnold Schwarzenegger, who knew Graham from bodybuilding competitions. “The way he knew how to work an audience was truly fantastic.”

Even as Coleman rose in the wrestling world, becoming more and more successful and famous, however, his private life was full of pain and chaos. He married and divorced three times before he met and started dating a bank teller named Madelyn “Bunny” Miluso. Their marriage quickly soured too, but they had two kids together. The couple stayed married, with Coleman spending most of his time on the road.

He was also secretly struggling with drug use. He started taking anabolic steroids in the late 1960s, when the synthetic male hormones were legal and prescribed by doctors who disregarded or didn’t know about the side effects. Coleman later said he thought steroids were “a wonder drug.”

“We were totally ignorant, we knew nothing about steroids, and they were easily accessible. Even the doctors had no clues,” Coleman said.

The long-term effects, though, can include liver, kidney, and heart damage, male infertility, extreme mood swings, paranoia, and depression. The performance-enhancing drugs also make people more prone to injury. Coleman hurt his hip and had to have it replaced, and then his ankles hurt so bad he could barely stand to wrestle.

Coleman also developed an addiction to amphetamines and barbiturates, attempting to regulate his moods with pills.

At the height of his career, however, a young woman named Valerie Irwin came into his life, bringing with her the possibility of a return to faith. Irwin, 19, was a committed, born-again Christian. She liked Coleman, who was 34 at the time, but refused to have sex with him. Instead, they talked, sometimes spending all night on the phone. They talked about how much they loved God and what they were reading in the Bible. Coleman was especially fascinated with creationism and the biblical account of Noah’s ark.

The couple got married in July 1978.

“Maybe I hadn’t known him for very long, but already I knew him better than anybody else,” Valerie Coleman said. “He literally is one of the best people I know, in his heart. He wants to be good. He isn’t very good at it. But he wants to be good.”

After Superstar Billy Graham was defeated by wrestling’s newest babyface champion, Coleman returned to Phoenix with his new wife and tried to get out of wrestling. He struggled financially, at one point installing sprinkler lines for a landscaper, and continued to be dogged by addiction. He returned to wrestling briefly in the 1980s, attempting to recast himself as a monk-trained karate master, but he didn’t know any martial arts and most fans thought the gimmick seemed like a gimmick.

Coleman finally, briefly, got to wrestle as a babyface in the Southeast. The bookers gave him a storyline where he was part of a satanic cult but went out into the desert, died, and came back wearing all white to save young girls from the Satanists.

Physical pain, combined with ongoing conflicts with Vince McMahon and the management of the rechristened World Wrestling Entertainment, forced him to quit for good in the early 1980s. He just missed wrestling’s entry into mainstream entertainment with cable television. In 1984, Hulk Hogan won the championship looking exactly like Superstar Billy Graham. Hogan even called people “brother,” just as Coleman had—an innovation he adapted from the way people addressed each other at revivals.

Coleman, meanwhile, had to hawk his and Valerie’s wedding rings to pay for a place to stay. He went on disability and moved into an extended-stay hotel. He also decided it was finally time to go back to church.

That’s where he met Jeff Fenholt, the Jesus Christ Superstar Broadway performer who converted to Christianity. Fenholt convinced Coleman he was still called to ministry, even after everything that had happened.

“You were called,” Fenholt said. “We can walk away from the calling, but the calling is always there. The Lord has allowed you to come full circle.”

Coleman joined Athletes International Ministries and spent his later years sharing his testimony and inviting people to accept Christ as their personal savior. He also reconciled with McMahon and apologized, publicly, for the way he’d left wrestling and tried to hurt the organization when he was angry.

“Sometimes with the born-agains,” McMahon said at the time, “you wonder if it’s an angle or not. I felt that Billy was telling me the truth.”

Coleman died of sepsis and multiple organ failure in a medical facility in Phoenix. He is survived by his wife, Valerie, and his two children from a previous marriage, Capella and Joey.