In May, Italy’s government called an emergency meeting over the rising prices of pasta. Italians have also been hit in the pocketbook by high natural gas prices, an expense of boiling water for cooking. In 2022, the Italian government recommended reducing how long home cooks boil pasta water as a thrifty “virtuous action.”

This is just one symptom of the recent surge in prices that makes paying for our daily bread difficult. Inflation has hit around the world, and with it have come different pressures on households. In the United States, the average lifestyle costs more than twice as much as it did in 1990. In Ghana, where inflation may be the highest in Africa, food costs twice as much as it did one year ago. Its last annual inflation figure was over 50 percent per year. Moth and rust, of a sort, have destroyed.

But there are other pressures on consumers to be thrifty, including a sense of responsibility to slow our waste. For example, America tosses about 13 million tons of clothing a year. And although there are hungry people, almost a third of the cultivated land in the world grows crops that will benefit neither humans nor animals. After that, about 14 percent of food is discarded before it even reaches a shop.

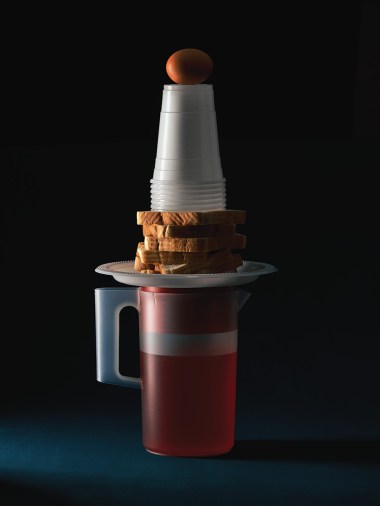

In view of our consumption and its costs, slack can feel elusive, and extra can seem outrageous. One response to these tensions of wealth, waste, and need always seems to have the stamp of virtue: thrift.

Thrift is a response to tradeoffs—to the choices we often make between having and eating our cake. It means using less, buying less, or spending less in order to redirect resources. Thrift may be a way of managing a small budget or big expenses, such as making money saved on used clothing stretch to cover fresh fruit.

But it may also be a way of avoiding waste, gaining for future financial ease, or preserving resources to last another generation. Thrift may even be about managing an image, projecting admirable qualities in a context where extravagance or new wealth is considered gauche.

Is thrift truly the virtue we often assume it to be?

Thrift has long been associated with a Christian heritage—as part of the Protestant work ethic Max Weber described, vows of poverty in Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox religious orders, and one of the most recognizable characteristics of Mennonites and other Anabaptists.

“The Protestant movement was an argument about money,” says Clive Lim, an investor and entrepreneur who has cowritten several books on Christians and money. He points to Protestant outrage at the Roman Catholic Church’s methods of earning and spending income. But he also highlights the prominence thrift had in dissenters’ teachings. To the Reformers and their successors, “no matter how much wealth you have, you have to live simply. Frugality is important.”

That is, Lim says, until the past hundred years, when high consumption became part of our idea of a healthy economy.

It almost goes without saying that it’s good to live within one’s means, and when those means are small or one’s needs are great—a situation many people are in now—thrift is a responsible and godly solution. Practicing it is nevertheless countercultural in the US and many other countries. “I think today we are being challenged on frugality,” Lim says.

If, as Lim points out, the issue of thrift is a spiritual one, then our task is to exercise frugality when we should (and differentiate that frugality from seeking God’s kingdom and righteousness). But some common tendencies frequently stand in our way, especially our dread of being told to live uncomfortably and our impulse to make money the standard of all worth and our sole solution for big problems.

Jesus does not mention thrift in his teachings recorded in the Bible, unless you count his guidance to not throw pearls to swine (Matt. 7:6) or telling his disciples to gather the leftovers of his miraculous provision of food for 5,000 (“Let nothing be wasted,” John 6:12). But Jesus frequently mentions money and how to manage it.

Victor Nakah, Mission to the World’s international director for sub-Saharan Africa, says that much of Jesus’ teaching on money can be summarized as “When you have an obsession with material things or your material needs overwhelm you, you then behave like you’re not part of God’s family.”

Alongside his teachings and parables on money and worry, Jesus lacked a permanent home (Matt. 8:20) and his own money was in a group fund (which Judas stole from, John 12:6). Second-century Greek philosopher Celsus reportedly described Jesus’ “shamefully” modest lifestyle as “disgraceful.”

When Jesus talks about money and possessions, it’s hard to escape the impression that depending on wealth seems to him as silly as putting your hopes in the value of a Beanie Baby collection—and that it’s because of mercy that he comforts rather than mocks those who are concerned about money. But it’s also because of his awareness that they are in danger of worshiping a false (and unreliable and all-consuming) god.

Jesus’ teaching is aimed at shifting people’s hope for rescue from Mammon to God and their orientation from what loses value to what has eternal value. How do we take on Jesus’ perspective of our wealth, position, appearance, entanglements, obligations, and financial priorities? Doesn’t thrift tie our right priorities together?

I have a clear early memory of first learning to ride a bike. When I had finally found enough balance for a few seconds of forward movement, my beloved brother toddled into my path. There was plenty of room for both of us on the sidewalk, but I mowed the little guy down and we both fell onto the lawn, sobbing.

Now I know that the reason I couldn’t avoid him was something called “target fixation,” which means that we aim for what we’re focusing on—no matter how much we consciously try to avoid it.

Jesus keeps telling us to take our eyes off money. And in many places and times—including in the church today—we see people falling into the trap of requiring more and more of it to feel good. But on the flip side, we too often think that the change we must make is from lusting after money to avoiding money. In this way, thrift can also become a target we fixate on, disorienting us and leading us to crash right back into Mammon.

Jesus’ words to his followers showed his disapproval of hoarding money, making wealth the capstone of a life, and believing that money will make us safe. But we sometimes miss another aspect of Jesus’ teachings: the importance of where we focus our attention.

As Christians around the world live through a period of discomfort—or worse—in their household budgets, even thrift can bring them dangerously close to the errors often attributed to greed. Any perspective that filters reality through money distorts our ideas of worth. And isn’t seeing worth as God sees it an enormous part of discipleship?

Thrift can make austerity seem like a virtue for all times. One story of early church ascetics says that a fourth-century monk, Macarius, got a bunch of grapes and sent them to another monk, who sent them to another, and so on. Each craved the grapes, but none ate them. They eventually returned (presumably wrinkly) to Macarius, who still didn’t eat them. The monks had proved their ability to deny themselves.

Such denial can be a response to a belief that possessions are hot potatoes, things to be divested of before they ruin us. Jesus did call at least one person to treat money this way (Matt. 19:16–22). But far from solving an obsession with money and possessions, this form of living on as little as possible can result in miserliness.

Lucinda Kinsinger, a Mennonite and author most recently of Turtle Heart, says, “If you’re focusing on thrift for the sake of being thrifty, you’ll just end up being a tightwad. If our focus is being a good steward, then we’re in a good place.” And if thrift is a way of stockpiling for greater personal wealth in the future, we should question our focus.

Asceticism doesn’t seem to be the primary spiritual danger in North America at the moment. Rather, we seem overeager to keep what we have, whether it’s a little or a lot.

Many evangelicals in the US are familiar with Dave Ramsey’s Financial Peace University, which claims to have trained nearly 10 million people, often in churches. This program and courses like it can coach people in how they spend and save, which is both a real relief and a way to be responsible with resources. But both tithing and saving up while eating “beans and rice. Rice and beans,” as Ramsey puts it, can coexist with service to Mammon. The change in our financial assets must be accompanied by a change in our hearts and our attention.

Nowhere does Jesus emphasize living below one’s means as a way to peace. That’s because peace doesn’t actually come from financially astute money management, even if it includes tithing.

Jesus did tell the rich young ruler, “Go, sell everything you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven” (Mark 10:21) and the crowd on the hill, “Sell your possessions and give to the poor” (Luke 12:33). These teachings of Jesus may be among the biggest hang-ups for Christians around the world.

Anabaptist Essentials author Palmer Becker points to the story of the rich young ruler as a summary of Jesus’ teachings on money. This isn’t widely practiced as the Christian standard.

Karen Shaw, author of Wealth and Piety: Middle Eastern Perspectives for Expat Workers, says that in her research on Middle Eastern perceptions of money, the idea of voluntary poverty was mind-boggling to those she interviewed. A very small minority among her Christian interviewees was familiar with modern voluntary poverty among Christians.

In the West, where people are more familiar with the idea, Shaw says, “I’ve been to so many Bible studies where [the rich young ruler] is discussed, and the whole discussion is about why this doesn’t apply to us—how we can get out of it.”

Sometimes we try to outsource the duty to take care of the poor—or to give at all. Nakah is concerned that Christians expect voluntary poverty of pastors and missionaries, rather than of themselves, thinking that those Christians they perceive to be more virtuous can shoulder the burden of living on little.

But, Nakah says, this is a misreading on more than one level. Not only must we all give, but also “there’s no virtue in poverty. Most people struggle because they think the Bible teaches that we ought to be poor.”

Jesus’ words to sell what we have and give to the poor were directed not only at the wealthy. Lim grew up in poverty and crowded conditions and says it was difficult for him not to think of money as a source of security. But as a Christian, he says, “you have to leave the past behind you” and figure out what is enough and what is extra.

What Jesus commands is “not just downsizing,” says Shane Claiborne, cofounder of Red Letter Christians and a member of The Simple Way, where neighbors try to live in a sharing community as the early Christians did. Claiborne says a truly Christian way of managing resources is more radical than we are often prepared for—more radical than thrift. It is the opposite of envy; it is acting on a desire to provide for others from what we have.

And yet, there is a difference between Jesus’ commands to the rich young ruler and to the crowd—the absence of the command to the group on the hillside to sell all they have.

Lim says, “All Christians, I believe, are called to provide for the poor. We are expected to sell what is precious to us to release us from the hold of possessions and at the same time to do good. The question is how much of our possessions to sell. The rich young ruler in Luke 18 was told to sell everything, but Zacchaeus promised only half [to the poor] and it was enough for Jesus. It was more about what is required to break the hold of money.”

Isn’t the simplest way to avoid financial fixations just to get rid of money and the need to manage it? We could spend it down or pool it with others, letting someone wiser make the decisions. Getting rid of our money will not clear us of our responsibilities, however. Jesus called out those who withheld money from family obligations and claimed it was set aside for God; to him, it was not holier to pledge all one’s wealth to religious causes than to take care of dependents (Mark 7:9–13).

Together, Jesus’ teachings seem to say that our responsibility to manage our wealth remains even as we are also called to give it away. Following Jesus is not just a matter of getting rid of possessions and money—dropping them down a well or melting them down.

Nor is there a specific amount of giving that makes us good Christians. The Bible points us to the truth that it is not the extremeness of an act of service or self-denial that pleases God. “If I give all I possess to the poor … but do not have love, I gain nothing,” 1 Corinthians 13:3 says.

“Our orientation must be framed through love of God and a love of neighbor,” Claiborne says. There is an eagerness in Christian love to “make sure everybody gets to experience the gifts of God.” If we don’t experience a desire to share, Claiborne says, we should question what is really going on in our hearts.

In other words, when we try to obey Jesus’ teachings on money by aiming at a percentage or amount that we can apply to every Christian, we are still aiming at money.

Henry Kaestner, an entrepreneur and the author of Faith Driven Investing, says that, similar to unjustified excess, spending that you don’t feel is spiritually dangerous. He says that, quite often, “your idols are what you can spend money freely on.” And Claiborne warns that we should watch out for defensiveness about what we have or what we spend money on, seeing that as a possible indication of idolatry. So carefulness ought to be part of Christian money management, even while we keep our eyes on Jesus.

But there’s a further misconception—one I think is less about spirituality than about mistaken thinking. It’s the idea that only a certain amount of money exists to spend on all the things in the world.

If that were the case, it would be unchristian and wasteful to spend on anything but emergencies. Like some Christians throughout history, we might believe that charity done right will suck all else dry. Thrift can become the lens we see through. Worship, fun, or anything not strictly necessary looks like waste.

Judas—though insincere—parroted this perspective when Mary of Bethany poured perfume over Jesus’ feet: “Why wasn’t this perfume sold and the money given to the poor? It was worth a year’s wages” (John 12:5).

The first time I read Beowulf, I was struck by one of its last scenes, where Beowulf, a hero who had been praised for bringing his people wealth, was buried with treasure. “Gold in the earth, where ever it lies / useless to men as of yore it was.” I balked, then thought again. What was that gold good for, anyway? It couldn’t have brought antibiotics to the North Sea. Nothing Beowulf’s people could spend would have resulted in children born in safety. Even unimportant delights were impossible then—Beowulf’s money couldn’t have bought puffer jackets, cardamom lattes, or peaches.

But today our money can buy such things and many more. There is more of value on Earth.

This possibility of creating new value means that expensive projects, like building a cathedral, don’t necessarily preclude someone else from getting a fair wage or a vaccination. Wealth is more like sourdough starter than a loaf of bread. Even in non-Christian terms, money just isn’t as limited as we can sometimes think.

Likewise, Jesus didn’t accept Judas’s objection that Mary should have sold her perfume and given the proceeds to the poor.

“Leave her alone,” Jesus replied. “It was intended that she should save this perfume for the day of my burial. You will always have the poor among you, but you will not always have me.” (John 12:7–8)

In other words, her worship (and its prophetic nature) was a worthy cause for pouring out a year’s wages. And her extravagance would not limit anyone’s ability to minister to the poor; the opportunity for that would remain—if Judas’s heart would allow him to give.

It’s not that waste isn’t a concern; it is. Jesus talks about it, too. There is, of course, the prodigal—or wasteful—son. In another parable, a wealthy man punishes one of his managers for not profitably investing money (Matt. 25:14–30).

“Waste is a bad thing. We never want to see a steward be wasteful,” Kaestner says. But the waste is less about whether an investment pays off than about a faithful process for spending money and an understanding of the true worth of what we can pay for.

There is a related danger—of depending on money as an all-purpose solution. If the problem is very simply too little money and you want to, for example, pay your employees higher wages, more money generally works, with a few cautions about tax brackets. But if you want to end homelessness, reduce corruption, or end conflict, there are aspects of these problems that do not respond to an infusion of money—and other aspects that respond to it like fire to oil.

Lim says he certainly found this when he was funding projects meant to help people. “In the beginning, I thought money was the solution,” he says. “I would throw money at it and hope the problem would go away.” But the problems came back. Now, he says, he knows “money isn’t a panacea. It’s narcotics. It doesn’t solve deeper problems. The money allows you to avoid the pain.” He still gives, but now he knows that it takes more creative ideas to really make a difference.

Money should not be the only Christian solution, “the answer for everything,” as the cynic in Ecclesiastes put it (10:19).

It’s necessary and responsible to insist on thrift and a lack of corruption when we give through organizations. But an emphasis on thrift can also make us lose sight of what money is good for. Are overhead costs too low? Are staff being asked to sacrifice what their families need—in terms of their time as well as their income—so that the organization looks good?

Or what if our constraints in giving to the poor diminish how we see God? Shaw, the author and researcher, says, “Because mission and church budgets are often really tight, we might come to think that God is a little bit stingy. We would never say it out loud, but you sometimes get that impression.”

Many of us know the poetry of Jesus’ words on the hillside:

Do not lay up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth and rust destroy and where thieves break in and steal, but lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust destroys and where thieves do not break in and steal. For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also. (Matt. 6:19–21, ESV)

For people around the world, literal rust and moths have destroyed what they had saved. Fires have melted and burned it. Politics have invalidated it. Inflation has reduced it. Money isn’t reliable. This lesson is fairly straightforward, especially to those who know it by experience.

Jesus’ second command in this teaching is harder, though. What can storing up “treasures in heaven” mean? He seems to be saying that our literal money can be exchanged for things of value to God himself. What would these things be?

Nakah says, “All that falls under the eternity category has to do with people, with changed lives.”

When asked about this principle of spending on what yields eternal blessings, Susie Rowan, former CEO of Bible Study Fellowship, said, “What immediately comes to mind is the Good Samaritan. He immediately interrupted his life to take care of the man” who was assaulted. And Jesus tells us to “go and do likewise” (Luke 10:37).

Nakah gives a less urgent example of a friend who funded a little girl’s education. Later, the girl became a believer, and the friend realized that what he knew to be important now (her education) had led to her eternal life.

Financial advice often focuses on the tradeoffs between present and future, encouraging people to stockpile and painting a vision of future wealth as the payoff for present thrift. Claiborne says, “That’s one of the consistent things I see in the teachings of Jesus. God rebukes the idea of stockpiling.”

This theology appears in the parable of the rich fool (Luke 12:13–21). Without Jesus’ condemnation, the story seems to be a morally neutral tale about a man using his successful harvest to provide for his future. The surprise for Jesus’ hearers, and for us, is his conclusion: “But God said to him, ‘You fool! This very night your life will be demanded from you. Then who will get what you have prepared for yourself?’ This is how it will be with whoever stores up things for themselves but is not rich toward God.”

Those who encourage thrift now to earn wealth later, Kaestner says, are “talking about compounded interest.” But they’re missing the best way to spend money: by investing in eternal things. That, according to Kaestner, returns “compounded blessings.”

Looking across cultures can be useful in seeing our own blind spots in how we use money, Shaw says.

In comparison to many other places, North America is clearly weak on hospitality. “I’m so grateful for the time I had in the Middle East where [there’s] this extravagant hospitality and this love of giving—it’s just been wonderful to be able to learn from people who reflect God in this way,” Shaw says.

Nakah adds that in his Zimbabwean culture also, people find hospitality and generosity to strangers to be quite natural. “If for some reason you get stuck in a village, you run out of gas—whatever homestead you go to, they will literally treat you like royalty. If there is only one bed, they will let you sleep on that bed. If there is one chicken, they will slaughter it for you.”

Something Nakah says he learned by looking outside his culture is that even quality time falls into the category of a treasure that can be stored up in heaven. “Speaking as an African, there is a lot to learn from Western cultures when it comes to the importance of saving for vacation, for anything that helps create memories,” he says.

Becker says another example of an eternal investment is a gift from his Anabaptist community to a friend in Ethiopia: a high-quality roof. “To their neighbors, it looks extravagant,” as most of them have thatched roofs that need frequent replacement. Becker sees it as the opposite of hoarding. “Inequality of wealth is one of the biggest problems in our society and in our world. How money is managed is very important.” What may appear extravagant in this case, he says, is both practical and a right use of their difference of resources. It will keep the friend’s family safer from the elements and mosquitoes as well as drain far less of their energy and money over time.

“Extravagance used rightly would be putting the best that you have in places to bring God glory without looking for others to see it,” Kinsinger says. It doesn’t even have to be a practical gift.

All our money management must be shot through with the consciousness of eternity—the worth of people, the value of worship, the disintegrating nature of our money, a confidence in God’s riches, and a participation in his eagerness to see creation flourish.

What can help keep our eyes on Jesus instead of on our resources? Once we have popped our illusions about money’s worth and reliability, and about living austerely, it is easier to consider Christian simplicity. Simplicity is what we really need to navigate the fluctuations in our wealth. And it may look surprisingly like thrift.

Thrift overlaps with simplicity, which is the fulfillment of Jesus’ command to “seek first his kingdom and his righteousness” (Matt. 6:33). Simple people, like thrifty people, may be indifferent to image. They find that enough isn’t always a little further out of reach and can contently live below their means.

This simplicity isn’t the same as being normal or average. “Give me neither poverty nor riches” (Prov. 30:8) is a cry not for a middle-class life but for a life in which money management has a minor role.

Simplicity allows us to see the worth of possessions and activities in light of Christ’s kingdom. It helps us welcome back the joy, beauty, and fun that thrift wants to cut out. But it doesn’t lead to waste or mismanagement. Rather, simplicity helps us understand worth.

Richard Foster wrote that simplicity is really about a singular focus on a “with-God life.” Someone who prioritizes prestige, comfort, and autonomy and also tries to squeeze in an interest in Jesus is not simple. But a biblically simple person could nevertheless be a financial whiz kid or a Proverbs 31 entrepreneur-manager-artisan.

While simplicity certainly marks a person, “we quickly learn that the outward lifestyle of simplicity will be as varied as individuals and the multifaceted circumstances that make up their lives. We must never allow simplicity to deteriorate into another set of soul-killing legalisms,” Foster wrote.

Nakah says simplicity is “a deeper appreciation of what Jesus has given us. You want a lifestyle that is easy to manage, where you’re not worried about your white carpet” and where “you can enjoy things without wanting to own them.”

Rowan agrees, especially since we cannot tell whether people are following Jesus’ teachings on money simply by looking at their tax brackets.

When we think of simplicity as a focus on Jesus, we can see how to balance the needs to not waste, to not find our worth in money, and to be generous and hospitable rather than stingy. What might look like a contradiction to non-Christians—being neither reckless nor tightfisted—can make sense.

One thing that will stand out most in a simple Christian life is radical generosity. It’s a generosity that doesn’t cement our social standing or yield returns in the form of favors or income. It’s a generosity that changes how we live.

When we consider how generous to be, thrift works against the good. But when we plan for generosity, thrift works for the good.

Shaw says that, unfortunately, evangelicals don’t seem to share Jesus’ own emphasis on God’s generosity. In the Gospels, she says, “there’s this wonderful sense of contentment with what God has given and appreciation for God.”

Jesus taught us to be dismissive of the worth of money. He can use any amount and could be as thrifty as feeding 5,000 with five loaves and two fish or as extravagant as accepting a gift of perfume that cost a year’s wages.

When we consider in what ways we can splurge, we should also consider what those items mean, Kinsinger says. Would a Land Rover be a help or a barrier to discipleship? What is the message our kids receive from a mountain of Christmas presents? Is a big wedding worth the cost? The answer might not be the same for each Christian.

One answer is the same. Should Christians ever be extravagant? “Yes, yes, yes, yes!” Shaw says. “How else can we be like the Father?”

So what remains seems to be in tension: We must take responsibility for ourselves and others with our wealth, yet we must not depend on wealth. We must not waste, but we also must not be obsessed with bookkeeping. We must share our wealth, especially with the poor, but we must know when to pour out a shocking amount in a gesture of worship or celebration. We must use money for eternal ends, but we must not take on Mammon’s pressures. We must develop wisdom about worth apart from what markets or culture dictate.

We’ll find both our balance and our direction by focusing on Jesus. In him we’ll see someone of infinite worth and infinite resources who is generous beyond our imaginations.

Susan Mettes is an associate editor for Christianity Today.