I was born outside the church—very far outside. Neither of my parents were Christians when I was a kid. We were a military family, my dad a Marine, and we bounced around several military bases, mostly in North Carolina. My dad was made of stone, a chiseled, highly decorated Marine who had served in the Vietnam War era. And while he was an excellent Marine, he was better at holding weapons and dodging bullets than he was at engaging with his family.

When I was 12 years old, my dad decided that domestic life was not for him. He abruptly left our family, never to return. Frankly, it is hard to describe the emotional trauma our family experienced when the strongest, most respectable man any of us had known simply walked away. With four kids to feed, my mom worked her tail off, and my siblings and I spent most of our time running the streets.

The same year my dad left, I started doing drugs and drinking alcohol. By age 18, I had been selling and using all kinds of drugs for years. During my senior year of high school, my friends and I showed up drunk to a basketball game against a local rival. I threw up on the other school’s principal, which promptly got me suspended. The days I missed pushed me over the limit for allowable absences, forcing me to repeat senior year.

By the time I finally graduated, I had joined wannabe gangs, gotten shot at twice, and been arrested. My senior class had voted me “most likely to live in a VW van.” I had grown dreadlocks, which made my marijuana-centered lifestyle a poorly kept secret. On graduation day, my principal awkwardly withheld my diploma and summoned me to his office. He and I were never on very good terms, but he felt duty bound to tell me I was following a destructive path.

After high school, I moved to the beach. But I grew bored of being a nowhere man, so I began pursuing a two-year community college degree in therapeutic recreation. It sounded fun, but I was hardly prepared. After a year of classes, I dropped out, sold everything I had (it wasn’t much), and left with my little brother to follow the Grateful Dead around the country.

We meandered for about a year, winding up in Northern California. Life resembled a counter-culture version of the movie Groundhog Day: Wake up, follow the music, find people to party with, pass out, go to bed—and then do it all over again.

After a cold, wet New Year’s Eve show, I couldn’t take it anymore. I was tired of the Grateful Dead, tired of hippies and the smell of patchouli, tired of waking up who-knows-where beside who-knows-whom. Perhaps more than anything, I was tired of not knowing where I was headed. Was partying, carousing, and floating around with hippies all there was to life? I told my brother I was heading to North Carolina, where I was planning to go back to school.

Then something unexpected happened. My oldest sister, who lived in California, was taking me to the bus station to say goodbye. We had never been a churchgoing family, but she was exploring Christianity at the time. She offered me her Bible, which I politely turned down. But she insisted, and I realized I was about to be stuck on a bus for a week with nothing but a guitar, a backpack, and a little weed. So I took her Bible.

A few days into this bus trip, my fingers were getting tired from constantly playing the guitar. Bored, with nothing to do but people watch, I took out the Bible somewhat disdainfully. Since I’d grown up in the South, the people I perceived as churchgoers were often people I also perceived as racists. It would be hard to overstate how little interest I had in going to church.

But I had never read the Bible, never considered Jesus apart from the people I associated with him. So there, in the back of a Greyhound bus, I opened God’s Word for the first time.

Many people get offended by being told they are sinners. I was not. As I read the gospel story, it was painfully obvious that I had mastered nearly every form of sin under the sun. I was deeply convicted.

In some ways, I felt more lost than ever. All my earthly idols—drugs, sex, the Grateful Dead—were leaving me empty and dissatisfied. And here I sat coming to grips with my real problem in life, which had nothing to do with finding a high I couldn’t come down from: I had offended the God of the universe—the maker of heaven and earth. The weight of my sins crushed me.

But the same Bible that showed me how great my sin was also showed me how much greater the Savior Jesus is. The gospel was beautiful to me. That Jesus had done for me what I could never do for myself—perfectly obey God’s law yet die to satisfy the wages of my sin—was the most liberating news I had ever heard. I was startled when I realized I was crying, overcome by the thought that such a well-practiced sinner could be washed clean, made whole, and given purpose in life.

I had climbed aboard that bus a long-haired, stinking Deadhead (bathing was not a high priority back then). I got off a week later with longer hair, smelling even worse, but saved. I had been washed in the blood of the Lamb and saved by the grace of God.

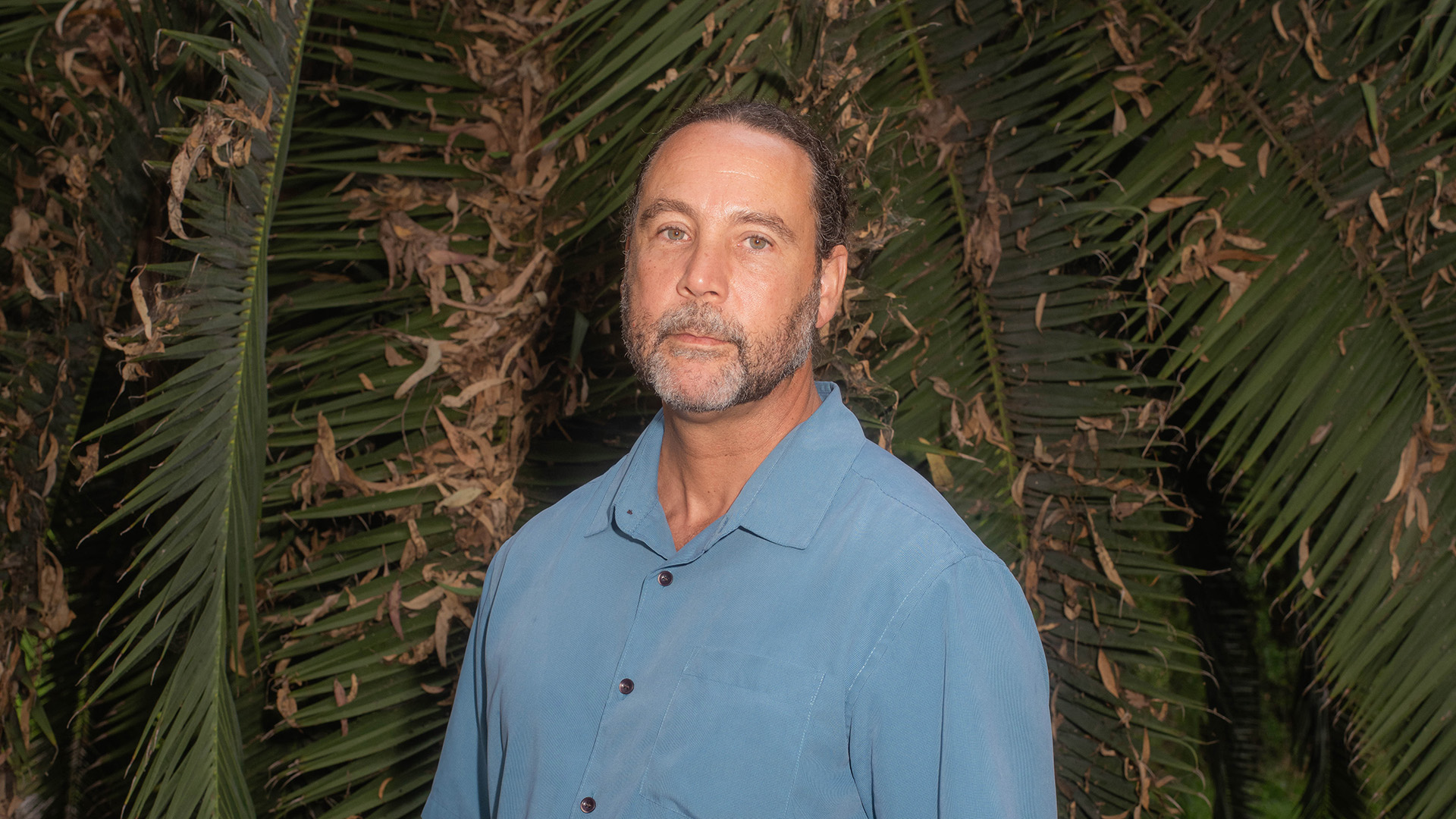

Alan Nakkash

Alan NakkashJust as captivating as the core gospel message was the promise that God is a Father to those who come to him by faith. A good, loving Father—one who would never walk out on you. Before my bus trip was over, I decided to take a detour and go see my dad. We had not spoken in years. But the anger I felt toward him had just been bested by the grace of God. In fact, I felt compassion for him. He was the first person I wanted to know that I had become a Christian. Even so, I had no idea if he would be willing to talk.

He welcomed me. It turned out that my dad had become a Christian that same year and was praying for a way to reconcile with our family. One of the most precious moments of my life was the day, a few years later, when my dad drove down to our family reunion. I watched in amazement as this man of stone—a man of few words—got down on his knees before his adult kids and grandkids and begged through tears for forgiveness. He then sang a Christian song called “Watch the Lamb.” It was his way of saying, “Don’t look to me; look to Christ.”

In God’s providence, I went on to finish that recreation degree. From there, I completed four theological degrees. I have been a full-time pastor and church planter for 22 years while teaching at numerous seminaries. But above all that stuff that looks cool on paper, I am a husband and father of four. God not only saved me from the path of destruction I was on; he also used the pain I’d experienced as a young man to shape me into the kind of husband and father I want to be.

God’s grace is relentless. He saves all kinds of people. He takes broken stories and broken vessels and makes them beautiful. What else would you expect from a God who raises the dead? He even takes former Deadheads and turns them into pastors.

Eric Watkins is the pastor of Harvest Orthodox Presbyterian Church in San Marcos, California. He is also the director for the Center for Missions and Evangelism at Mid-America Reformed Seminary.