My first encounter with the Rothschild name happened in a thrift store. I was maybe nine years old and ran across a little wool dress coat just my size. The tag said “Rothschild,” and when I showed my find to my mother, her eyes lit up. “The Rothschilds are very famous and wealthy,” I remember her saying. “That’s probably a very nice coat.”

I don’t remember how nice it was, and at the time I didn’t know enough to wonder whether the Rothschilds, whose company made my coat, were connected to those Rothschilds, the remarkably successful banking family whose name is a longstanding byword among conspiracy theorists and antisemites. I think I wore it under the impression that the child in Rothschild was a family tribute (Roth’s child), or perhaps a nod to their sale of children’s attire.

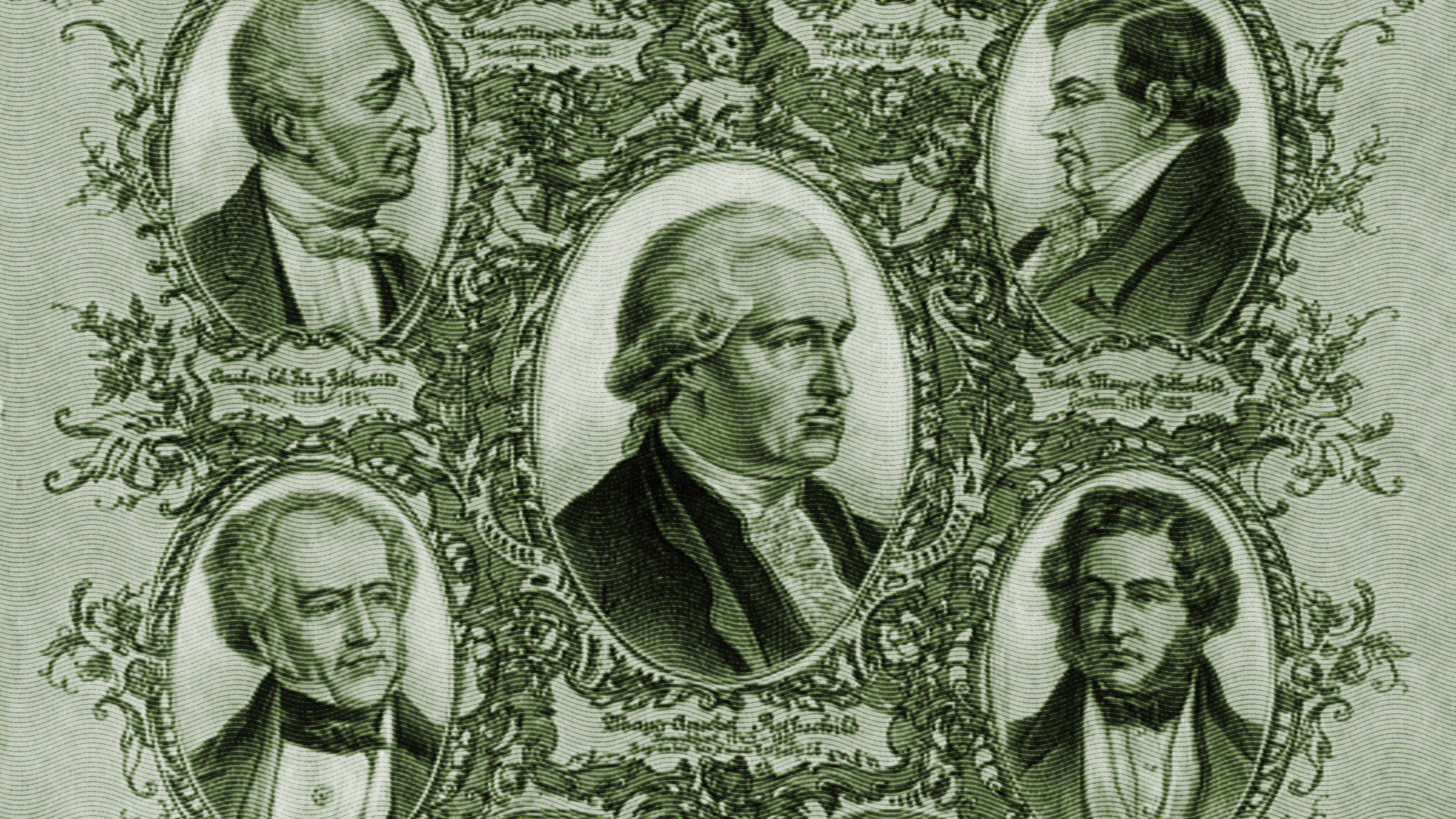

But the seam in the word is not after the S but before it: roth-schild, from the German for “red shield.” It’s a reference to a marking on the home where Mayer Amschel Rothschild lived as he founded the family dynasty in the 18th century. By day, he served in the court of the princely House of Hesse, and at night, he returned to the cramped quarters of the Judengasse, Frankfurt’s prison-like, one-street ghetto in which Christian authorities literally locked the local Jewish population every night and every Lord’s Day.

That’s but one small piece of the history covered in Jewish Space Lasers: The Rothschilds and 200 Years of Conspiracy Theories, a new release from journalist Mike Rothschild, who is—as the delightfully clever cover notes—“no relation” of those Rothschilds. The subtitle undersells the scope of the work, which traces the family’s history from 1565 to present and examines the global development of Jewish tropes, legends, and conspiracy theories along the way.

The Rothschild allure

“It is a sprawling story, told over centuries and continents,” as Rothschild writes in his introduction, replete with “fake Russian counts, Parisian pamphlet wars, lizard people,” and so much more. Thus does Jewish Space Lasers cover everything from the Judengasse to the Battle of Waterloo to the titular lasers—the idea, pitched in a 2018 Facebook post by Georgia Republican Marjorie Taylor Greene before she ran for Congress, that a California wildfire was the result of a Rothschild-involved conspiracy to advance green energy projects and, of course, make gobs of money.

Rothschild promises early on that his book is “not a biography of the Rothschilds, nor is it a deep archival study of their various business ventures,” nor “an examination of the political and societal forces at play” in the many ways the Rothschilds have affected world history. It’s a promise he doesn’t quite keep and perhaps couldn’t have: To effectively reject the idea “that Jews control everything, and that the Rothschilds are the ‘Kings of the Jews’” requires quite a lot of biography, archival study, and examination of the political and societal forces. And if Jewish Space Lasers bogs down in detail, this, too, is encouraged by the subject matter—the book is repetitive, but so are the conspiracy theories.

But negative perceptions of the Rothschilds are not all Rothschild has in view. Perhaps the most pleasant surprise of Jewish Space Lasers was its peek inside Jewish culture around the storied family. “For many Jews, the Rothschilds have been a beacon of hope in dark times, a reminder that anything is possible with unity and a steadfast devotion to family and tradition,” Rothschild explains. “They were heroes who fought tenaciously for the freedom of other Jews, while never giving in to the temptations of conversion and assimilation.”

The Rothschild allure was as much about their faithfulness and generosity as their aspirational wealth—but the wealth was part of it too. For example, the source text for Tevye’s “If I were a rich man” refrain in Fiddler on the Roof originally read “If I were a Rothschild.” And Tevye’s goals there are bigger than three staircases. “If I were Rothschild I would do away with war altogether,” he muses. “You will ask how? With money, of course.”

I knew going into Jewish Space Lasers that money would be a big part of the story. It’s impossible not to anticipate that, if you have any knowledge of our culture’s stereotype of Jewish people as—in the phrase of the first chapter’s title—“greedy, cheap, and blessed.” And I knew, too, that centuries of gross and officially sanctioned antisemitism would come into it; the history of how some European Jews came to be bankers was already familiar.

But much of what Rothschild recounts was new to me, supplying a remedy for an ignorance both happy and untenable: happy because it came from a lack of exposure to explicit antisemitism; untenable because antisemitism is persistent and pernicious, and because it is difficult to push back against evil if you fail to recognize it when you see it.

New extremists and old tropes

One place we see the evil of antisemitism, of course, is in church history. Though Rothschild has a light touch in connecting antisemitism with Christianity, never painting with too broad a brush, the bulk of his tale is set in Christendom Europe. Even outside overt misuses of our faith to oppress Jewish people, then, the story of the West’s antisemitism is undeniably a story about people who at least professed Christianity, whatever was in their hearts.

This history—of expulsions and pogroms, blood libel and other slanders, forced conversions and baptisms—is galling and repulsive. It’s also absurd, because the core of our faith is that God became man and, as Rothschild observes, that man was Jewish.

Christian antisemitism can only exist through blatant rejection of God’s commands (Eph. 2:11–22) and scandalously stupid misreadings of Scripture (Rom 1:16, 3:29, Gal. 3:28). But there’s no escaping the fact that it has existed, and not only in centuries past. Greene, the space-lasers theorist and a sitting member of Congress with a large, popular following, professes an evangelical faith, having been baptized at the Atlanta-area North Point Community Church in 2011. In his 1991 book The New World Order, the late Pat Robertson, erstwhile head of the Christian Coalition, cited explicitly antisemitic works—books with chapter titles like “The Real Jewish Peril”—to posit a conspiracy of malevolent global domination, with the Rothschilds in on the scheme.

Are things getting any better? Considering the present and future state of antisemitism, Rothschild takes a dim view in the book and online, where he greeted this week’s news of war in Israel with worry for how it will affect Jews worldwide, because, “[h]istorically, whatever can be blamed on Jews will be, no matter their nationality.”

This century has seen a disturbing “resurgence of public and unapologetic antisemitism,” he argues in Jewish Space Lasers. Today, “new extremists are espousing the same hateful tropes that were once relegated to being fodder for fringe pamphlets and whispered accusations. But now they aren’t fringe, and they aren’t whispering,” Rothschild contends. “They are a danger to everyone. And they’ll never stop—because they never have.”

I hope he’s wrong in that prediction, and I wonder if he hopes it too. After all, why write a book-length debunking of hundreds of years of antisemitic theorizing unless you have some hope that it will help? Not, perhaps, to the point of persuading confirmed antisemites, but at least to educate the rest of us and shock us well away from a hateful path that too many have trod.

Bonnie Kristian is the editorial director of ideas and books at Christianity Today.