Athanasius Yohannan, who built one of the world’s largest mission organizations on the idea that Western Christians should support “native missionaries” but got in trouble for financial irregularities and dishonest fundraising, died on May 8. He was 74 and got hit by a car while walking along the road near his ministry headquarters in Texas.

Born Kadapilaril Punnoose Yohannan and known for most of his ministry as K. P., Yohannan founded Gospel for Asia in 1979. Over the next 45 years, the organization trained more than 100,000 people to preach the gospel and plant and pastor churches in India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and other places in Southeast Asia, according to a recent ministry report. Gospel for Asia raised as much as $93 million in a year and in 2005 reported it was supporting about 14,500 indigenous evangelists and pastors in same-culture and near-culture ministry. Christians in the US were asked to give $30 per month to support them.

“If we evangelize the world’s lost billions … it will be through native missions,” Yohannan wrote for CT. “The native missionary is far more effective than the expatriate. The national already knows the language and is already part of the culture. In many instances, he or she can go places where outsiders cannot go.”

Yohannan’s death was mourned by Gospel for Asia, the church that he started and served as metropolitan bishop, and prominent political leaders in India.

“He will be remembered for his service to society and emphasis on improving the quality of life of the downtrodden,” Prime Minister Narendra Modi wrote on social media. “May his soul rest in peace.”

Both the governor of Kerala and the leader of the opposition in the state assembly released statements offering condolences, saying Yohannan’s death was a great loss.

In Yohannan’s final “Shepherd’s Letter” as the head of Believers Eastern Church, he urged his followers to remain disciplined and faithful.

“During our time on earth, we are embarking on a journey to become more like Christ,” he wrote. “I am so proud of all of you for your faithfulness to the church and for your thirst to become like Christ our Lord. The greatest desire I have for all of us is that we are known by our love for others.”

Yohannan was born on March 8, 1950, the youngest of six sons in a family that raised ducks. They lived in the village of Niranam, where a stone monument in the local Orthodox church memorializes the arrival of the apostle Thomas in the year 54.

His mother was a devout Christian and, as Yohannan later told the story, secretly fasted and prayed that one of her sons would grow up to be a minister. She didn’t think it would be her youngest, “Yohannachan,” however, because he was so shy and insecure. When he announced at 16 that he was dedicating his life to serving God and fulfilling the Great Commission to make disciples of all nations, she gave him 25 rupees (about 30 cents US)—his first donation.

Yohannan said he was inspired by a missionary team that was raising support for work in northern India.

“As they explained the desperate need of the subcontinent, I felt a strange sorrow,” he wrote in 2019. “That day I vowed to help bring the love of Jesus Christ to those mysterious states to the North. At the challenge to ‘forsake all and follow Christ,’ I somewhat rashly took the leap, agreeing to join the student group that summer.”

But then the missionary organization turned Yohannan down. He was too young and hadn’t even finished high school. The rejection stung. He recalled how much it hurt even decades later.

“I had nobody to stand with me,” he told a newspaper reporter in 1980. “There were no churches or missionary societies to say, ‘Hey, we’re behind you.’”

Yohannan was, however, allowed to attend a training program in Bangalore the next year. That was the first time in his life he wore shoes, he later recalled. In Bangalore, Yohannan heard George Verwer, founder of Operation Mobilisation, challenge people to live and die for Christ. That night, Yohannan prayed, giving his whole life to Christ and committing himself to “breathtaking, radical discipleship.”

He joined Operation Mobilisation and started street preaching—experiencing the empowerment of the Holy Spirit in the process.

“I felt a force like 10,000 volts of electricity shooting through my body,” Yohannan wrote later, describing his first sermon. “All at once God took over and filled my mouth with words of His love. I preached the Good News to the poor as Jesus commanded His disciples to do. As the authority and power of God flowed through me, I had superhuman boldness.”

Yohannan traveled around India with Operation Mobilisation for about seven years. He met and married a German missionary named Gisela. His youth was noticed by Western missionary leaders, such as John Haggai, who praised his talent and charisma and challenged him to do great things for God.

The young evangelist’s relationship with his missionary teammates was not always good, however. Some felt that he wanted attention too much and that preaching gave him an inflated sense of importance. At one point, as he later recalled, no Operation Mobilisation team would work with him.

“You are proud and arrogant,” one of the leaders told him. Another said, “Nobody wants you. No one can help you. Only God can help you.”

After that, Yohannan decided to move to the United States to get more ministry training. He went to Criswell Bible Institute (now Criswell College) in Dallas and took classes for two years. He was ordained in a local Baptist church.

As he considered the prospect of pastoral ministry, however, Yohannan felt himself drawn again to missions. He began to pull out world maps at a Tuesday-night Bible study and led the Baptists in prayer for the people of faraway places, as George Verwer had often done. He talked to the Christians about giving a dollar a day, or $30 a month, to missions.

In 1979, Yohannan and his wife started Gospel for Asia, based in Texas. The ministry established its India headquarters four years later, according to Gospel for Asia.

Yohannan published Revolution in World Missions in 1986. It was part autobiography, part critique of Western missions, expounding Yohannan’s theory about the superior effectiveness of national evangelists. The lost do not need your missionaries, he told Christians in America and Europe. They need your money.

“The Holy Spirit is moving over Asian and African nations, raising up thousands of dedicated men and women to take the story of salvation to their own people,” Yohannan wrote. “These national missionaries are humble, obscure pioneers of the Good News taking up the banner of the cross where colonial-era missions left off.”

Yohannan did not go so far as to call for the withdrawal of Western missionaries from Asia or other parts of the world, but he did argue that sending people from the US and Europe was a bad use of resources, unwise, and colonialist.

Gospel for Asia grew quickly. According to the ministry, Western funds were going to support 4,500 native missionaries by 1990. Gospel for Asia has reprinted Revolution in World Missions seven times, and there are now about 4 million copies in circulation.

Yohannan also started his own church in 1993. Believers Church was conceived as an indigenous Indian denomination, separate from Western influences, but also more evangelical than some historic Indian churches.

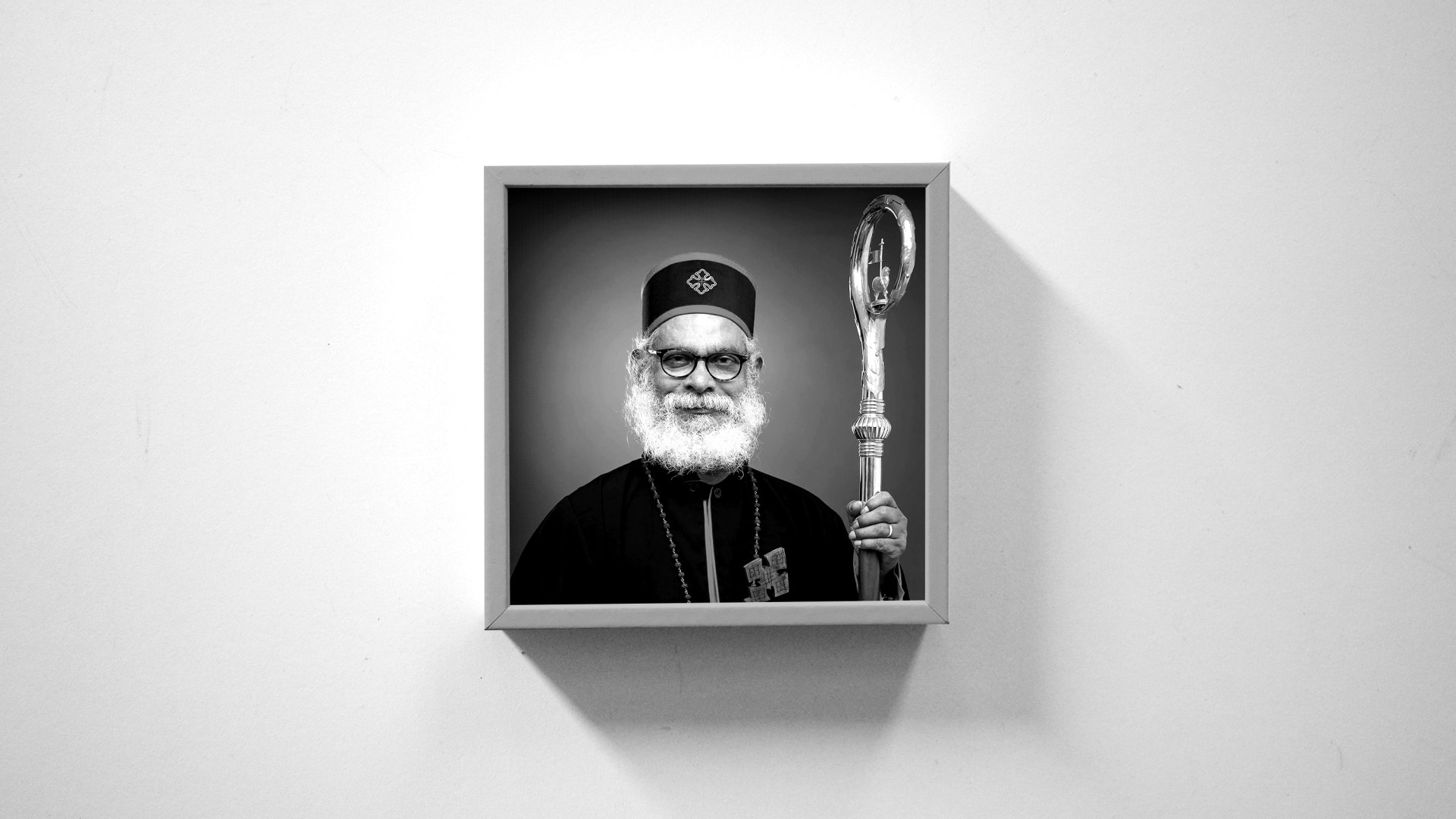

Over time, the church adopted a more Eastern Orthodox style. Yohannan was elevated to bishop in a service in 2003 and claimed apostolic succession. He took the title “Metropolitan,” to designate himself the head of the church’s bishops, and the honorific “Moran Mor,” which is similar to the Western designation of “Most Reverend” or “His Holiness.”

The increasing emphasis on authority raised concerns for some Gospel for Asia staff.

“K. P. functions as an episcopal bishop,” a group of them wrote, “and wears the robe, hat, ring and some other accompanying items. Staff and leaders there commonly kneel or bow and kiss K. P.’s ring in a sign of veneration. … This is not how Jesus taught and modeled authority.”

Yohannan denied that anyone kissed his ring, but the staff members released photos and videos. They also reported he had started to teach that disobeying him was a sin. If he told a staff member to move to Myanmar, Yohannan reportedly said, the correct response was “yes sir,” not “I’ll pray about it.”

The staff raised additional concerns about fundraising issues, prompting an investigation by the Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability (ECFA). In September 2015, the ECFA concluded that Gospel for Asia had violated five of seven standards. The ministry misled donors, soliciting donations for specific purposes and then using the restricted funds for other projects, including the construction of a new headquarters. Some of the movement of money was not properly documented.

Blogger Warren Throckmorton reported on the roiling scandal extensively at the time.

Yohannan appeared to be unaware of the basics of nonprofit management and the board failed to provide adequate oversight, according to the ECFA.

Gospel for Asia acknowledged it had been “unintentionally negligent” but also pointed out that no one had personally benefited from the financial irregularities and that no money was found to be missing, even if it wasn’t all where it was supposed to be.

The ECFA took the unusual step of expelling Gospel for Asia.

Some donors sued the ministry, claiming their funds were misused. Gospel for Asia ultimately settled, agreeing to refund $37 million to a class of 200,000 donors. The ministry did not accept any guilt, however, and the terms of the settlement required plaintiffs to agree that “all donations designated for use in the field were ultimately sent to the field.”

Several prominent evangelical leaders spoke out and endorsed Yohannan’s integrity, including George Verwer, pastor and author Francis Chan, Anglican Church in North America bishop Bill Atwood, and D. James Kennedy Ministries president Frank Wright.

“I cannot say enough good things about K. P. Yohannan and all my friends at Gospel for Asia,” Wright said. “This ministry is exceptionally effective, fully Christ-centered and worthy of broader support.”

Chan, the author of Crazy Love, said he had examined Yohannan’s life—his tax returns, his home, his car, and even what he ate—and was convinced he had not taken any money or enriched himself or his family with ministry donations.

“How could anyone accuse someone like this [of] fraud and racketeering and trying to take money?” Chan said. “It just doesn’t make any sense.”

After the expulsion from the ECFA, Believers Church decided to change its name to Believers Eastern Church to emphasize the difference and distance from Western evangelicalism.

In 2018, the bishops all took the names of early church fathers, martyrs, and saints. Yohannan chose Athanasius, a fourth-century theologian from Egypt known for his writings on the Trinity.

After that, he was referred to by the church as Athanasius Yohan I. Toward the end of his life, his writing focused on the biblical basis for liturgy, ritual prayer and prayer ropes, the importance of tradition, the use of incense in worship, and the sacrament of Communion.

He continued to lead Gospel for Asia until his death.

“We are called to be witnesses for the Lord Jesus Christ by telling people about His love through words and actions,” Yohannan wrote to the church about a year before he died. “My dear children in Christ, please remember that if we live for the Lord and are His witnesses, we will have to go through suffering, whether it’s persecution, misunderstandings, or other problems.”

Yohannan is survived by his wife, Gisela; their daughter, Sarah; and son, Daniel, who is now the vice president of Gospel for Asia.