When you stand in the southeast room of the Green-Meldrim House, a Gothic Revival mansion in Savannah, Georgia, the discomfort you may feel is not paranormal.

Though located in the self-proclaimed “most haunted” city in America, the unease of this house is about history, not ghost stories. Here, on January 12, 1865, 20 Black pastors met with Union general Tecumseh Sherman and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton to discuss Black Americans’ new life of emancipation with the Confederacy nearly defeated.

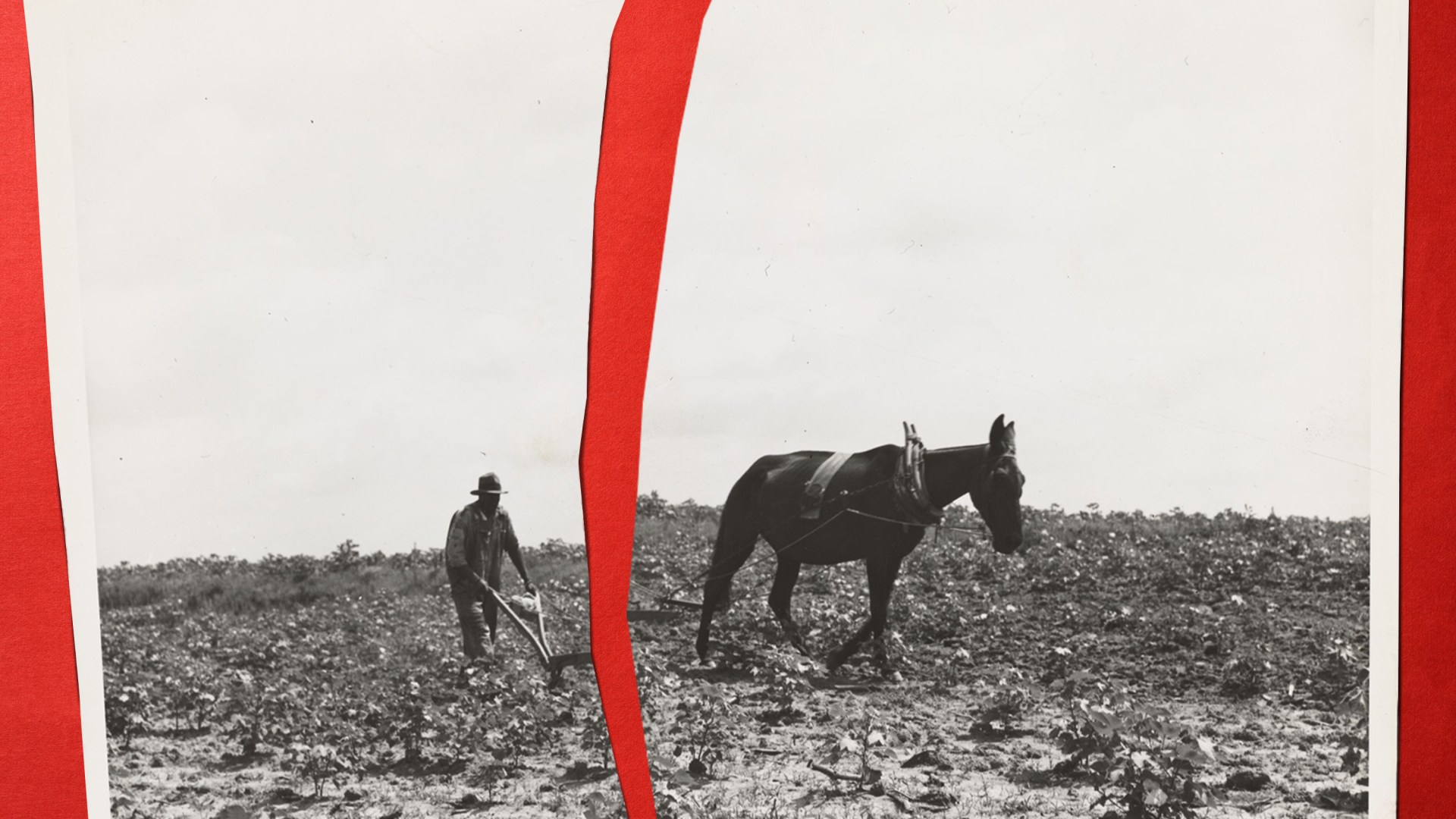

What came from that discussion was Special Field Order No. 15, commonly known as “40 acres and a mule.” Sherman, Stanton, and the federal government promised newly freed people the right to lease, then eventually buy, some 400,000 acres of confiscated land along the Atlantic coast, stretching from South Carolina down to Florida.

Abolitionists of all backgrounds and Radical Republicans had advocated for this kind of land redistribution for many years, but it was Black pastor Garrison Frazier who told Sherman and Stanton that the way freed people could “best take care of ourselves [was] to have land.”

“We want to be placed on land until we are able to buy it and make it our own,” Frazier said. And after days of deliberation, the order was ratified.

But just a year later, when Andrew Johnson assumed the presidency following Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, the justice of Special Field Order No. 15 was thwarted. Johnson vetoed legislation intended to give real heft to the Freedmen’s Bureau. He restored to its prior owners much of the property confiscated from the tyrants of the Confederacy instead of leasing or selling it to freed people who had worked the land.

As I stood in the Green-Meldrim House earlier this year, in the temporary quarters of Sherman himself, quieted by this sinister tale, I began to feel the haunting of history. It was a too-familiar feeling of broken promises.

In Scripture, promises are a fortification of fellowship, provision, and flourishing. God repeatedly makes and fulfills promises to his people. When Yahweh promised Canaan to the descendants of Abraham, he wasn’t solely providing economic and social autonomy. Yahweh set his people free so they could worship him (Ex. 7:16). This was a dignifying promise that provided land, liberty, and legacy.

The Bible has much to say about broken promises, too. Joshua honored a covenant with the Gibeonites, even though it was established under deception (Josh. 9:16–20). Four centuries later, when Israel failed to uphold that promise, God sent a famine as judgment (2 Sam. 21). If God holds entire nations accountable for the promises of their ancestors, do we imagine that this nation—in which so many claim the name of Christ—would be exempt?

Those 20 pastors at the Green-Meldrim House were seeking much the same as what God promised Israel: to have land and liberty to worship the God who brought them out of Egypt. The promise of land in Special Field Order No.15 was no trivial mea culpa for slavery. It almost looked like a covenant, reflecting biblical principles of shalom and reconciliation.

Then that promise was broken, and no one should be surprised. This country—of freedom and liberty—has a habit of plagiarizing biblical principles even as it violates them. Black Americans in particular have spent generations and generations in hope of repair. Instead, many promises have been revoked, even as we’ve watched America keep its promises—even grant reparations—to other people groups and noncitizens.

President Ronald Reagan signed a bill to pay $1.6 billion in internment reparations to Japanese Americans for injustices during World War II. Decades later, in connection to that same war, President Barack Obama authorized $34 million in compensation to citizens of Guam for violent acts and occupation by Japanese forces. Compensation has been paid to Filipino war veterans, families victimized by 9/11, and even slaveowners who freed slaves during the Civil War.

Our country has not accorded the same care to its Black citizens—not because that project is impractical but because our government is unprincipled. It has acted not with the faithfulness of God but with the deceit of Laban, taking our labor without delivering the promised reward (Gen. 29:25).

That history has tangible consequences: This type of treatment atrophies economic empowerment. Many politicians blame Black poverty on government dependency, but they miss or ignore the effects of America’s broken promises to Black people—of which “40 acres and a mule” is just one.

Those betrayals are often explained away as a matter of “fairness” or a call to “personal responsibility.” Johnson opposed Field Order No.15 because he believed it advantaged Black people over white. This has been the rhetoric for close to two centuries, including within the American church. Too often, Black Americans facing hardship are deemed lazy or pathological, while other Americans facing the same hardship are met with empathy and understanding of the systemic factors involved.

But our hardships—and specifically Black poverty—have systemic sources, too. This is a theological as much as a historical truth. As theologian Christopher J. H. Wright has argued:

Oppression is by far the major recognized cause of poverty. The Old Testament asserts, as all modern analyses demonstrate, that only a tiny fraction of poverty is “accidental.” Mostly, people are made poor by the actions of others—directly or indirectly. Poverty is caused. And the primary cause is the exploitation of others by those whose own selfish interests are served by keeping others poor.

The evangelical work of many Bible believers today is twofold: convincing the world of the reality and nature of personal sin and discipling fellow Christians toward an awareness of the systemic results of that personal sin. On some matters, like abortion bans, those Christians easily understand the need for systemic change. But when it comes to systemic racism and its economic effects, too often they are unable or unwilling to see how sinful individuals contribute to sinful social systems. I share Leo Tolstoy’s lament that “even the strongest current of water cannot add a drop to a cup which is already full.”

I have little faith that our government will ever truly repent of its atrocities toward Black Americans by making restitution. But I pray Christians will practice mundane acts of equity and repair, through personal service and communal practices. Let us keep our covenants with each other (Matt. 5:37) and remind our elected leaders, who take office with hands placed on the Bible, to do likewise: “Do not break your oath, but fulfill to the Lord the vows you have made” (Matt. 5:33). Let us sing of Zaccheaus, who modeled a towering repentance that was personal and systemic (Luke 19:1–10).

All things broken are called to be repaired: cognitive and corporeal, local and global. And when the government abdicates responsibility for the sake of expediency, we must practice endurance. My Christian ancestors had endurance in the most horrendous of circumstances, yet they sang. And now they worship in spirit and truth, with true freedom.

I don’t pity those 20 pastors who met with General Sherman, nor the many saints they served, who now experience a more glorious acreage than any 40 acres of the South, lit by the radiance of the Son. I pity the living who continue to endure the haunting of broken promises.

Sho Baraka is the editorial director of Big Tent at Christianity Today.