The wake-up call came over the loudspeaker and sank into our barrack’s stone walls. It was still dark outside and cold. I shifted under my quilt and guessed the time. When Blake returned from the showers, there would be an eight-minute window to get up, break down our institute-issued mattresses and wooden bed frames, put on the correct uniform, and walk to formation.

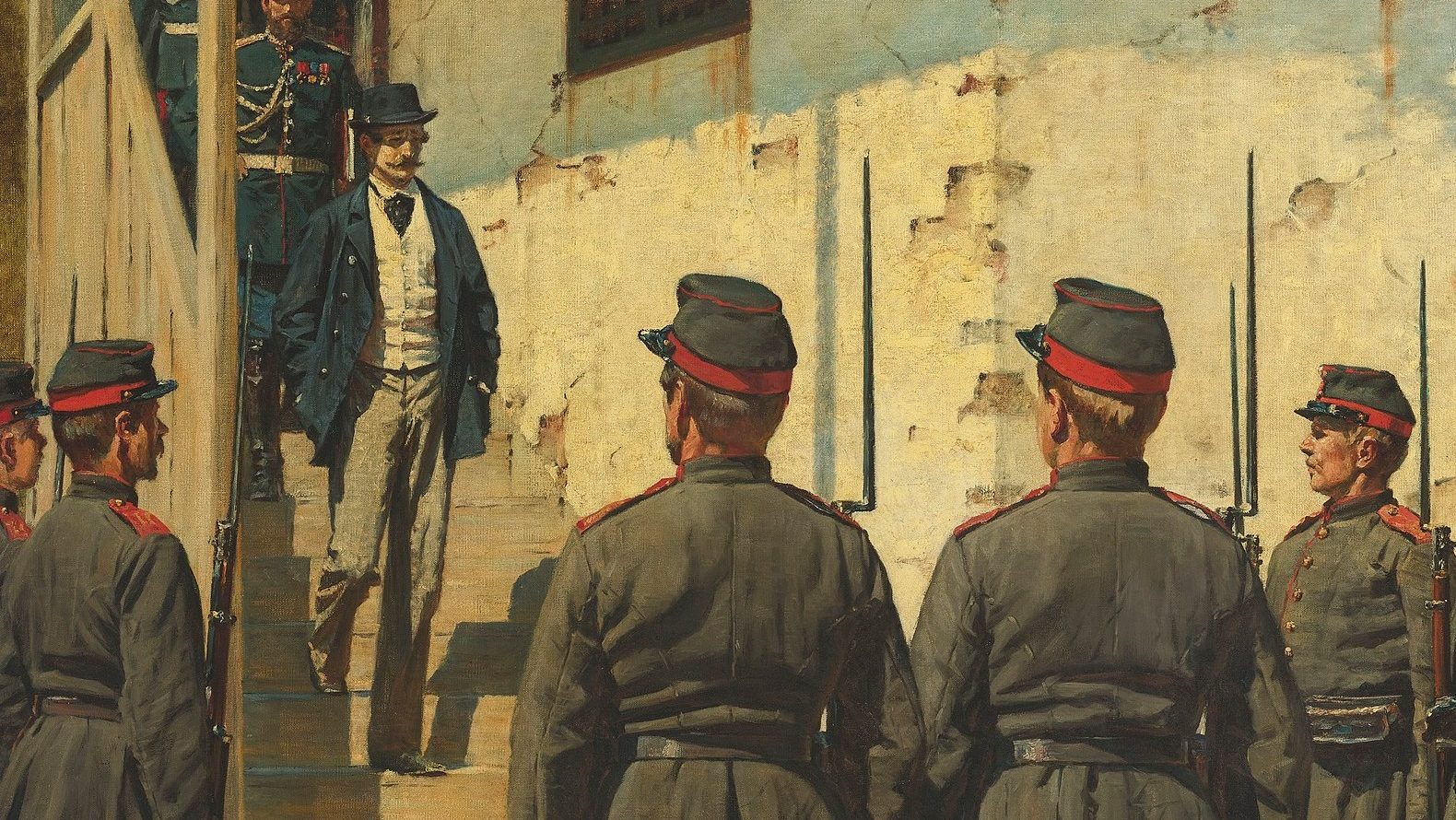

Our heavy wooden door swung open. My mental timer started. I rolled out of bed and wordlessly began the day. I put on “winter class dyke,” our cold weather uniform: grey wool pants that were notoriously itchy until you wore them for a few days, and a long-sleeve black button-up with a corresponding black tie.

I tucked the tie between the shirt’s second and third button, a mid-century GI style that our superintendent preferred, then opened the door and listened. The Virginia Military Institute bustled in the darkness. Another muffled announcement: “Class Dyke. Rain cape. Rain cap cover.”

Naturally, we all tired of the strict regimen and sameness of our uniforms. When leaving post for an open weekend or furlough, we relished putting on normal clothes. It was always odd seeing friends in civilian attire; 90 percent of the time with them was spent in uniform. The oddness was also due to the wild divergences in style, until then undisclosed. There were Hawaiian shirts, cargo pants, hipster fits, tactical clothing brands, wild fluorescent colors, skater fits, tank tops, and other methods of asserting one’s individuality. The result: cacophony.

But somehow, outside of their uniforms, my friends seemed less like themselves.

Swathes of modern dressers, just like Virginia Military Institute cadets, are trying to assert their identity against the group, against that unnerving sameness that pervades modern style. Walk across a college campus or a shopping mall, and you will notice waves upon waves of athleisure wear and ubiquitous configurations of popular trends. In response to this homogeneity, many dressers are desperately trying to be unique. Bright colors. Bizarre mismatches. Ironic kitsch. Clothes that are sausage-link-skinny or grocery-bag-baggy.

As Ezra Pound and the Vorticist movement declared a century ago, the only rule is to make it new. Uniqueness has become the standard by which fashion is measured. Yet uniqueness is no longer measured in relation to the town or community; one must compete with a global network of new. Social media is a constant stream of trends and fads that leave the individual scrambling to find something exceptional.

The current proliferation of options means a further individualization of style. Clothes have largely abandoned utilitarian purposes. We no longer think about what we wear primarily in regard to a vocation. Although we have “work clothes,” these are only a fraction of our wardrobes.

Americans buy four times as many new articles of clothes as they did in 2000, even though one study found that we don’t wear 50 percent of the clothes we own. Even worse, every year, we prematurely throw out approximately 400 billion dollars’ worth of clothing. Of course, fast fashion accelerates our already extreme consumption and waste. Manufacturers are producing 100 billion new garments (globally) per year. This is more than ten times the number of people on earth.

This surplus, symptomatic of a broader affluenza that is both personally and ecologically harmful, has also changed how we see our clothes. They have become signals, more than ever, of how we conceive of ourselves. Today, it’s less about representing a group or a socioeconomic status and more about defining a personal ethos or, in modern parlance, a vibe.

When we conceptualize style as a project in order to assert the authentic self against the masses, we begin to dress like Transcendentalists. Transcendentalism was an early 19th-century literary and philosophical movement that sought to reestablish individual flourishing in the face of a rapidly industrializing economy, a default intellectual conformity, and a tumultuous political era, which would soon culminate in the American Civil War.

If we peel back our current anxiety about unique style, we find that this tradition of thought has helped define the American cultural imagination for 200 years. Understanding the dangers of Transcendentalism might help us reconceive how the individual can relate to society, revealing how our style can move past the reactionary and endless search for newness.

This tradition is not the only one to have contributed to the hyper-individualization we see in culture today. There are many major philosophers and thinkers who have described the relationship between the individual and society as antagonistic. There’s Nietzsche’s fictional character, Zarathustra, who heroically rejects the masses of “last men.” There’s Freud’s Civilization and Its Discontents, a bleak book in which the individual willingly accepts societal oppression in exchange for safety. And, moving out of the 19th century, there’s Camus and Sartre and their individualized brand of existentialism.

But in this essay, I’m interested in this widespread and pervasive movement (largely in the West) that has made the individual the arbiter of identity. The Transcendentalists, specifically Ralph Waldo Emerson, offer a clear presentation of the broad themes that these various philosophies uphold, making Transcendentalism an ideal representative.

In Emerson’s famous essay “Self-Reliance,” he writes, “Man is timid and apologetic. He is no longer upright. He dares not say ‘I think,’ ‘I am,’ but quotes some saint or sage.” Emerson fears that true education and meaningful action are giving way to mimesis, where the individual merely parrots a sage or popular opinion, never daring to think for themselves.

Although this danger was more pressing in the early 19th century when tradition held an authoritative position in social and educational life, we still face the essential danger of groupthink, which has proliferated rapidly through digital communication.

Surveying his cultural moment, Emerson concluded that “society everywhere is in conspiracy against the manhood of every one of its members.” This persistent struggle between society and the individual forms the bedrock of his response. If society is a crushing force, the individual must respond with gritty independence.

Emerson counsels, “Insist on yourself; never imitate”—a mantra that ought to sound extremely familiar. It’s posted (in some version) every day on every social media platform. It’s behind the clerk at the DMV. It’s hanging in your dentist’s office. It’s proclaimed by influencers and politicians and your grumpy uncle. We don’t exaggerate when claiming that this insistence upon the self is a fundamental ethos of the American national identity.

I certainly don’t want to demonize Transcendentalism. It can offer a helpful and often necessary corrective. It startles us out of the dangerous lullaby of rote tradition. It asks us to take account, to face ourselves. It calls for heroism.

As another early 19th-century American, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, would write, “Be not like dumb driven cattle, be a hero in the strife.” In this heroic approach to the self, Transcendentalism urges us to embrace action and accountability for our lives. Thoreau’s famous opening to Walden, “I went into the woods because I wished to live deliberately,” is one of my favorite passages in American literature. He earnestly desires to see for himself, to “cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner.”

Transcendentalism is a philosophy with a pumping, vital heart. Yet its adherents’ correction—as with so many other philosophies—overreaches, swinging us toward consequences that can be disastrous if left unchecked.

The first consequence of rampant Transcendentalism is that the individual becomes isolated from others and tradition. “It is only as man puts off from himself all external support and stands alone, that I see him to be strong and to prevail,” Emerson writes. “He is weaker by every recruit to his banner.”

The strong Transcendentalist is by necessity alone; Emerson calls for the removal of all external support. Solitude is not always lonely, but when all support is cut and every “recruit” turned away, the individual is dangerously isolated. When our actions and thoughts lose the barometer of community, they can careen wildly. Hermitage is almost always unhealthy.

Furthermore, if human community weakens the individual, then nonhuman community, like tradition and culture, present a similar danger to the Transcendentalist. Tradition is a form of communion, with Chesterton memorably describing it as the “democracy of the dead.” Transcendentalism, however, casts a disparaging eye on tradition. Recall Emerson’s lament about the “saint or sage,” admonishing readers to preference individual belief over inherited wisdom.

Second, Transcendental individualism is erratic and volatile, closely correlated with increased isolation. Because the individual is only accountable to himself, he achieves an odd infallibility. Listen to Emerson’s confidence: “Suppose you should contradict yourself; what then? … Speak what you think to-day in words as hard as cannon-balls, and to-morrow speak what to-morrow thinks in hard words again, though it contradict every thing you said to-day.”

The emphasis is not on truth or congruity; instead, the most important factor is that the words be spoken with resolute conviction, “as hard as cannon-balls.” Authenticity becomes the measurement of our speech, regardless of whether our “authenticities” vary from day to day.

Our search for a unique, individual style manifests both of these philosophical consequences. Our wardrobes are increasingly defined by isolation (you have to be “one in a million”) and volatility (the trends are wild and fast; see “sardine summer”). Because we have abandoned the judgment and taste of tradition, we are left with the avant-garde. And the avant-garde is constantly changing, constantly pushing further. A cursory review of the Met Gala displays this trajectory. There is nowhere to rest.

As long as we dress like Transcendentalists and set ourselves against society, we’ll be trapped between the dichotomy of dressing like the dull masses or breaking with all convention. While this binary is ultimately false, it does highlight a central dilemma: Can I express myself without being ostentatious? Can I imitate others without being dominated by tradition?

We can give an affirmative answer to both questions, but to do so, we need a different paradigm to capture the relationship between the individual and society. I’d like to offer one as an exemplar: the interpersonalism of Martin Buber.

In his famous book I and Thou, Buber explores two distinct modes of relating to the world: I-It and I-Thou. The first mode (I-It) relates to the world as a series of objects that can be used instrumentally and coordinated within our tasks. The second mode (I-Thou) relates to the world as a reciprocal encounter that transcends instrumental use. In an I-Thou encounter, we are influenced by the other as we influence them, and neither of us is coerced into a relationship of “use.” Buber extends these paradigms in a number of philosophical, sociological, and theological directions.

Crucially, beneath each of these extensions is a fundamental claim about the self: “Man becomes an I through a You.” Rather than positioning the individual contra others, Buber makes the relationship between others (and the Other, God) the central feature of our identities. We have no conception of a self without the other, through whom our self is constituted and contrasted.

Both ways of relating are necessary, but each way is dependent on context. In an I-Thou relationship, both parties mediate each other; imagine two children playing with a jump rope, shaking their respective handles. The waves sent from one side influence the other and vice versa.

In an I-It relationship, only one side mediates, attempting to control and use the other. In this case, only one of our players swings the rope. The other side is motionless and completely defined by the movement of the other. Obviously, this is appropriate in some cases (such as bringing my coffee mug to my lips) but harmful in other cases (such as trying to emotionally control my friend).

Importantly—don’t miss this—the silencing can happen in both directions. I can impose myself on others. Or society can impose itself on me. A true relationship is always a balance: “Relation is reciprocity.”

Buber’s interpersonal philosophy, like Transcendentalism, has important and far-reaching consequences. First, it resolves our central dilemma. Because the individual’s relationship with others is reciprocal (I-Thou), we can relate to society without silencing others or losing our voice. The rope can move on both ends.

Second, interpersonalism shifts the telos of style. Rather than establishing myself, the goal becomes relating positively to other people. We begin to dress for the other. This doesn’t mean pandering, seducing, or mimicking. It means that we understand our responsibility toward others; after all, we are helping to constitute their self as well. We are the Thou to their I. Each of us bears a responsibility to model to others what we value in the world.

We can feel this when talking around children. We realize that children soak up the speech and habits of adults, so we are especially careful with our words. We know our words have influence.

Your style has influence too. It’s a contribution to a collective conversation. For good reason, menswear writer Derek Guy has compared style to language. Stylish fashion is a dialogue with culture and society. As mentioned before, this dialogue must go in both directions. We have to guard ourselves from being swept up and defined by larger trends, while also recognizing that all of our choices emerge from past traditions and historical precedents.

Back at the Virginia Military Institute, our uniforms weakened our personal voice, quieting our end of the rope. In response, cadets shook the rope wildly when the opportunity arose, losing the balance in the opposite direction. But the uniforms also produced a sense of collective identity, both among ourselves and with past school traditions. Successful style needs balance and reciprocity. Can we achieve this tender tension today?

Thankfully, there’s a common (although underappreciated) custom that offers individual agency while tying us to a broader community: the dress code. Although dress codes have grown more and more niche (reflecting the hyper-individualism of fast fashion), they do offer a kind of practical solution for developing lasting and meaningful style. At their core, they are a set of conventions that can direct our choices. When I read “business casual” or “cocktail attire,” I am given constraints that encircle a wide range of individual possibilities. Both ends of the rope move.

Next time you’re wondering what you should wear to dinner, ask yourself: “What would Martin Buber do?” Maybe relating your fashion choices to dead philosophers is just what you need to make your style decisions for the evening.

Whatever you do, don’t be like Ralph. Keep him tucked away in the drawer. We don’t need to forfeit individual style, but we can make little choices that bring us closer to the world around us. Because it’s only in relationship with others, as in life, that style can blossom with balanced freedom.

Carter Davis Johnson is a writer and teacher whose work has been published in Road Not Taken, Flyover Country, Warkitchen, Rova, New Verse Review, and Front Porch Republic. He also writes a Substack publication called Dwelling: Embracing the non-identical in life and art.