I am a slave to beauty.

My mother was an art historian, and my father was a literary junkie who had read the entire canon of Western and Eastern masterpieces by the time he was 20 years old. Some of my earliest childhood memories are of being carted around in a stroller across London, speeding through the Tate Modern, the Tate Britain, the National Gallery, and the National Portrait Gallery.

Almost every childhood holiday involved my sweaty child hands being pulled through the Louvre in Paris, the Uffizi in Florence, and almost every cathedral in continental Europe while Mum took notes. She would sit me down in front of the Impressionists and try to explain to her ungrateful boy the impact of linseed oil on paint.

Meanwhile, at night, my dad would put me to bed by telling stories out of Tolkien’s The Silmarillion. Until the age of 24, I was convinced that the great war fought under the Two Trees of Valinor that gave light to the world was a creation of my dad’s imagination, until I realized he was simply a wonderful plagiarist.

It was a privileged upbringing, and I am infinitely grateful for it; it has served me well throughout my life. But it produced in me the most awful of faculties: that thing we call “good taste.” Other people call it “pretentious,” and C. S. Lewis called it a “gluttony of the subtler kind.”

Truth be told, aesthetic value often means more to me than moral value. I find bad art more offensive to my soul than crime. Despite my best intentions, I find it hard to resist the impulse to roll my eyes at the mediocre and to critique the great and the good. And nowhere is my eye more critical than when it turns to Christian art—even from its very beginning.

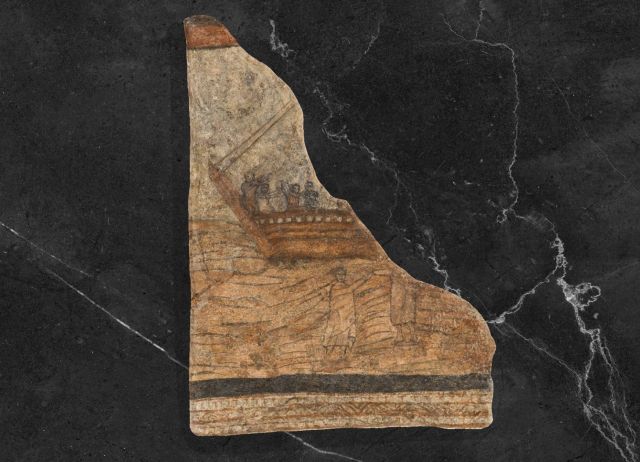

Christ Walking on Water, AD 249, New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery. Wikimedia Commons. Edited by Inkwell.

This is one of the earliest Christian depictions of Jesus. Can you see him? Painted on faded Roman plaster around AD 240, the painting shows four disciples perched on a boat, raising their hands toward two people on the water. There’s Peter, decapitated by 1,800 years of history and erosion. And next to Peter, holding his hands, is a figure wearing a flowing toga, the seams vanishing into the seams of the water.

Does he have hair? It’s hard to tell, but he seems to have some pretty intense eyebrows. Behold the man—ecce homo—here is Jesus. The water-walking God-Man reaches his hand out to the terrified Peter and says over the storm, “Take courage! It is I. Don’t be afraid” (Matt. 14:27).

This little panel was discovered in the baptistry of a converted house church built into the walls of Dura-Europos, one of the most eastern cities of the Roman Empire. In a city that pulsated with the strength of Rome, crowded with temples to the gods of the world, a motley community of Greek, Syriac, and Latin speakers met to worship their God. And in the back of this house was a small, windowless room with a pool built into the wall—the baptistry.

The walls are painted in burnt umber tones that tell stories from the Bible, including our water-walking Jesus. If you were a new believer, you would have been led into this room with the whole community, oil lamps illuminating the drawings in the flicker of smoky candlelight. You would have gone down into the depths of the cool water, hearing the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. As you blinked the water out of your eyes, you would lock eyes with your Savior—Take courage.

It’s a beautiful scene. But if I’m completely honest, if I take off my gold-tinted sentimental glasses and put on my well-trained, curated, beauty-intoxicated European eyes, it’s actually kind of a rubbish, pastiche drawing.

Jesus’ arms are disproportionate to his body, and anyone with a working knowledge of human anatomy can tell you that human legs are meant to be more than two sticks. It looks like the kind of thing a child would bring back after the obligatory Noah’s ark Sunday school session. Part of me wishes it were Rembrandt’s Prodigal Son greeting me on the wall instead.

Beauty is very much on the lips of today’s theological, philosophical, cultural, and social discourse. Modern man “doubts the truth, resists the good, but is fascinated by beauty,” wrote Cardinal Godfried Danneels. Christians from across the aisle have taken up the call: Make Christianity Beautiful Again. How many times have I seen and heard the Dostoevsky quote “Beauty will save the world” typed over pictures of Gothic cathedrals or Italian marbled paper?

It seems the agenda is set. We must appeal to beauty as our chief apologetic. Beauty is the call from God himself—drawing us upward and outward, propelling us beyond the closed realm of a physical universe and into the realm of splendor and delight, which ultimately calls us into the presence of the divine. And to this I say hallelujah, amen.

Yes to patronage of the arts. Yes to poetry nights over lectures. Yes to attending to the details of the human experience of Christian worship and prayer. But in all these things, let us not become aesthetes—addicts to the aesthetic. Let us not become Christians of good taste, idolaters of beauty.

Let us remember that beauty is also a terrifying and accursed thing. The most powerful gifts from God can become insidious and soul-destroying curses. One of the oldest myths in the Western world is about how powerful men went to war for the sake of beauty. When Napoleon ordered the invasion of Italy, he did so in part to take possession of the best paintings.

When we appeal to beauty, we are playing with serious firepower. “We don’t consume beauty like a commodity—beauty consumes us like a fire,” said French philosopher Jean-Louis Chrétien. Beauty is persuasive, seductive, violent, even! We don’t grasp it. It grasps us.

Beauty captivates us, which means that it also takes us captive. So powerful is its force that we can confuse an aesthetic experience with a mystical one. It is entirely possible to find what is evil and foolish to be beautiful. Satan himself comes as an angel of light and beauty.

Like everything under the sun, beauty needs redemption for it to be used for the good pleasure of God. And redemption is always shaped like the Redeemer: crucified, dead, and resurrected. The crucifixion of Jesus was supremely ugly—a disfigured, beaten, bent, tortured body, unjustly murdered. Yet by it, we are made beautiful in the sight of God.

If we are to have a Christian conception of beauty, it must be one that is crucified and resurrected. Jesus, who had “no beauty or majesty to attract us” (Isa. 53:2), gave us eyes and hearts to understand that beauty itself has been transfigured on the cross.

As St. Bonaventure wrote, “Who would look for beauty of form now in such a roughly-handled body? The most beloved Lord is stripped naked … who possessed neither beauty nor form … yet it was from this [ugliness] of our Saviour that the price paid for our beauty streamed forth.” And that’s why those paintings from Dura-Europos had such an impact on me—they condemned the man of good taste.

Christian art is beautiful insofar as it speaks of the truly beautiful one, the crucified one. As those early Christian believers went under the water of the baptismal font and rose to new life, face-to-face with an artistically disfigured Christ, they encountered the beauty of beauties.

The Dura-Europos Christ reminds me of another encounter I had with a water-walking Jesus. One thousand eight hundred years ago and five thousand miles away in Hong Kong, there is a mural of Christ walking on water.

It adorns the wall of a drug rehabilitation center run by one of the most faithful missionaries of the 20th century, Jackie Pullinger. Painted directly onto white concrete, Jesus walks across an acrylic sea. Behind him is not the dusty landscape of Galilee but the skyline of Hong Kong, and Peter is about to step out onto the water, reaching out toward Jesus.

The paintwork can’t compare with anything in the Louvre or the Uffizi, and the human proportions are slightly off. Yet this has been the Christ who has accompanied thousands of addicts, gang members, and prostitutes through deep darkness and into his beautiful light, and it is under the gaze of this Christ that they were baptized. It is this Christ who, every morning, hears the sweet sound of worship from their lips. When I was confronted with this painting, I sobbed at the beauty of it.

If we are to make Christianity beautiful again, we must keep this Christian experience of beauty at the very heart. Otherwise, all we’ll do is replace the idols of good arguments and reason with aesthetic craft and beauty. I, for one, am desperate to be a person of good news rather than good taste.

So can beauty save the world? Who knows. The jury is still out. But one thing we know for sure is that a saved world is beautiful. Lord, give us eyes to see.

Daniel Kim is the cofounder and head writer of ChristianStory, an animation project bringing to life the history and theology of Christianity. He is also the Anglican curate at St. Aldates church in Oxford.