This piece was adapted from CT’s books newsletter. Subscribe here.

1929: Inside the Greatest Crash in Wall Street History–and How It Shattered a Nation

Viking Drill & Tool

592 pages

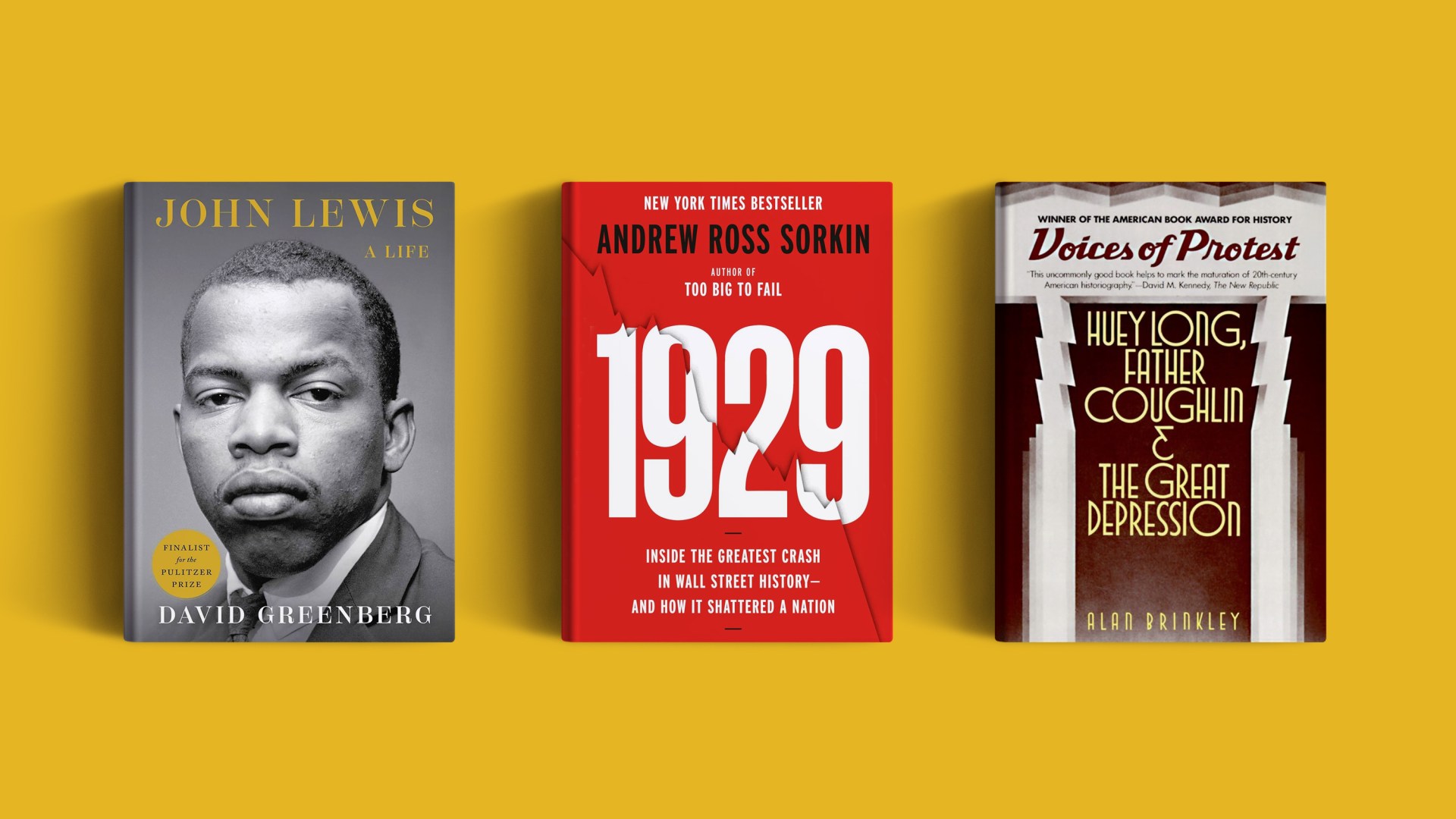

Andrew Ross Sorkin, 1929: Inside the Greatest Crash in Wall Street History—and How It Shattered a Nation (Viking, 2025)

In his 1933 inaugural address, Franklin Roosevelt explained why saving the economy required a heavy dose of federal intervention:

The money changers have fled from their high seats in the temple of our civilization. We may now restore that temple to the ancient truths. The measure of the restoration lies in the extent to which we apply social values more noble than mere monetary profit.

Andrew Sorkin, the author of 1929, agrees with Roosevelt. The crash could have been avoided if only humility and a sense of limits were able to overcome the darker sides of human nature: greed, ambition, and an addiction to optimistic thinking.

At the center of Sorkin’s story are the speculators: Charles Mitchell, Thomas Lamont, William Durant, J. P. Morgan, Jr., Jesse Livermore, and others. They spread the “gospel of economic opportunity” and tried to stop all efforts from the Federal Reserve to cool down the markets. By 1930, 8 million people were out of work. One thousand three hundred banks had failed. President Herbert Hoover called it a depression.

Sorkin rejects the idea, still bandied about in high school classes today, that Hoover caused the Great Depression. He argues that such an interpretation is the legacy of a well-orchestrated Democratic smear campaign in the years leading up to the 1932 presidential election.

Sorkin is such a compelling storyteller that readers with little knowledge of economic or financial history will enjoy and learn from this book.

David Greenberg, John Lewis: A Life (Simon & Schuster, 2024)

John Lewis loved to preach. As an eight-year-old boy growing up in rural Alabama, he preached to chickens. In his definitive biography of Lewis, historian David Greenberg chronicles how Lewis fulfilled his spiritual calling not in churches but at Nashville lunch counters, Greyhound bus stations, the Edmund Pettus Bridge, and ultimately the House of Representatives. “Race was closely tied to my decision to become a minister,” Lewis once said. “I wanted to use the emotional energy of the Black church to end segregation and gain freedom for Black people.”

Lewis’s life, as Greenberg tells it, is a story of dogged persistence in the fulfillment of this calling. Lewis was put on this earth to do one thing—end racial injustice through nonviolent protest. He never wavered from that task, even when this vocation led to physical beatings that brought him to the brink of death.

The story of Lewis’s early years will be familiar to those who have studied the Civil Rights Movement. Greenberg covers it well. But his biography also takes us beyond Selma and the March on Washington. He tells the story of Lewis’s career in politics, his relationship with American presidents, and his marriage to Lillian Lewis.

John Lewis lived a life defined by hope, justice, peace, and love. His story reminds us that amid all of today’s polarization and political strife, there is a better way. Greenberg’s biography is a good starting point for those interested in walking this path.

Alan Brinkley, Voices of Protest: Huey Long, Father Coughlin & the Great Depression (Vintage Books, 1983)

Populism rules today in American politics. Democratic socialists like Bernie Sanders gain political traction by reminding people that most of the nation’s wealth is concentrated in 1 percent of the population. Donald Trump has captured a significant portion of the white working class with promises of manufacturing jobs and nostalgic longings for a Christian nation.

For those who want to think historically about 21st-century American populism, Alan Brinkley’s 1983 book Voices of Protest is worth revisiting. Brinkley focuses on Louisiana governor and US senator Huey Long and popular Catholic radio preacher Charles Coughlin. Both men gained national attention in the 1930s as critics—from the left—of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal.

Long was known for his bombastic personality, mesmerizing speeches, attacks on big businessmen like John D. Rockefeller, and proposal to redistribute the nation’s wealth to benefit ordinary working people. Coughlin believed that Catholic social teaching required him to use his radio platform to promote the expansion of American currency through the monetization of silver.

Long and Coughlin were both showmen with large audiences. Brinkley argues that their activism was informed by a distinct populist ideology. They appealed to middle-class Americans reeling from sudden economic change and concerned about the concentration of wealth and power in fewer hands. Brinkley’s book offers a window into the appeal, weaknesses, and danger of American populism and, in the process, provides insight into our current moment.

John Fea is visiting fellow in history at The Lumen Center in Madison, Wisconsin, and distinguished professor of history at Messiah University in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania.