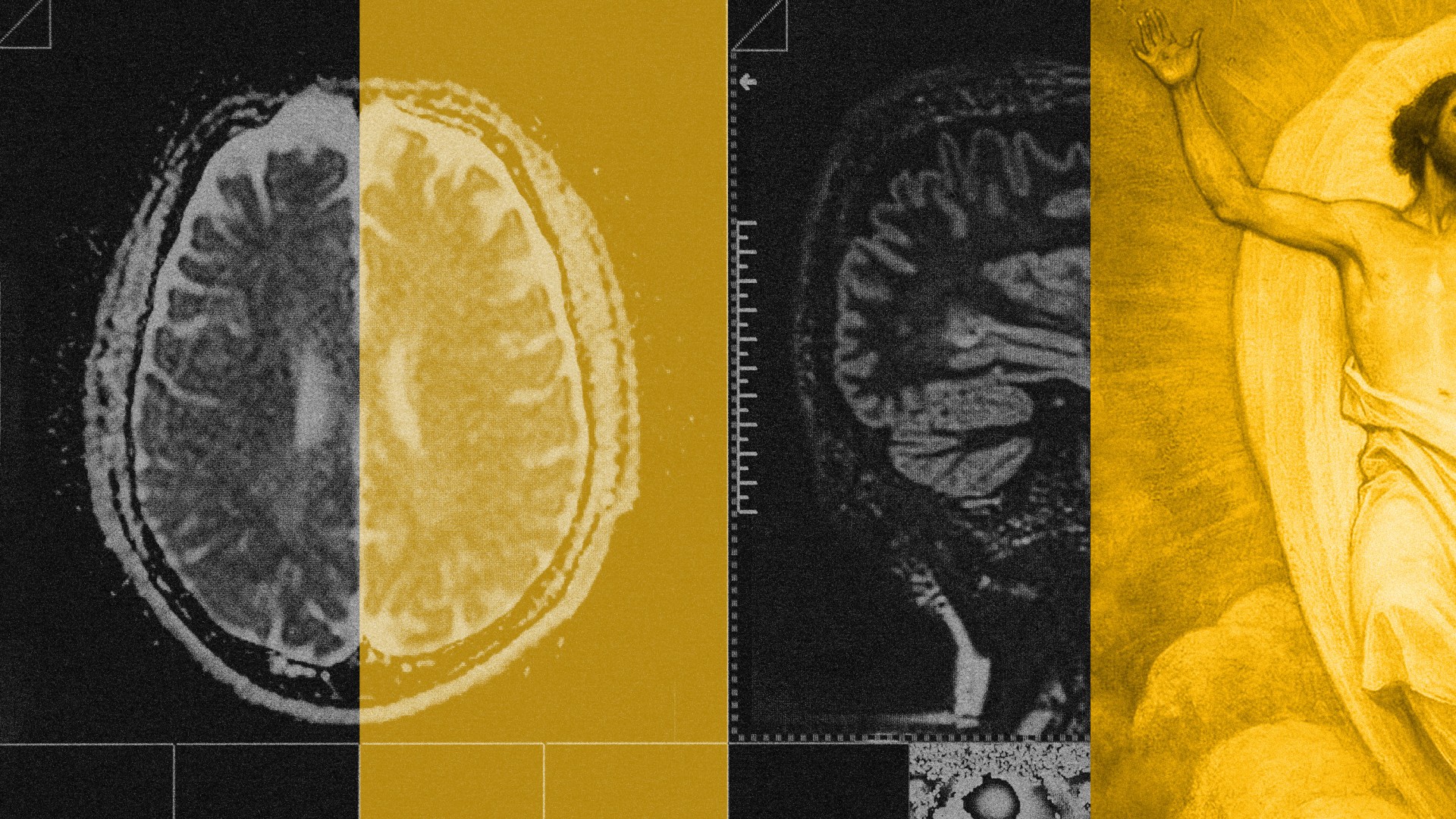

Scripture calls the church one body with many members, an image that expresses a spiritual reality through a physical one. It can be tempting to think of this idea—many members, one body—as pure metaphor, a gesture to the symbolic closeness between members of the church, and nothing more.

In her postdoctoral research on chronic pain at Stanford University’s School of Medicine, Yoonhee Kim, a Christian and a psychologist, views the scriptural idea of human interconnectedness as integral to our understanding of our brains and bodies. Kim’s clinical findings at Stanford, as well as her predoctoral work at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, emphasize how tangibly our relationships with others and our cultural contexts shape our emotions, minds, and bodies.

Recently, Kim and I connected for an interview about her work. She explained why we need to understand physical suffering in the context of social factors and how the biblical view of human beings as embodied creatures formed to live in community can help us approach one another with wisdom and care. The conversation has been edited for clarity, brevity, and length.

In your work at Stanford’s children’s hospital, you call pain a “biopsychosocial” phenomenon. I’m used to thinking of physical distress as a purely material phenomenon. Can you help me understand the factors that contribute to our experience of bodily pain?

Pain is entirely processed in the brain and functions as the alarm system for our bodies. Let me give you an example: You put your hand on a hot stove. The receptors from your hand send signals up your nervous system to the brain, alerting various parts of the brain with this information. The brain quickly assesses the situation, concludes the hand needs protection, and sends down a pain signal to the hand, which prompts you to jolt your hand away from the hot stove. Over time, your brain recognizes that the danger is no longer there, which allows the pain signals to dial down and eventually stop.

This is clearer to understand for acute pain—the sensation of a hand on a hot stove, breaking a leg, stubbing your toe, et cetera. Now, in the case of chronic pain, or pain that lasts for more than three months, there may or may not be an external trigger. For example, a teen girl may complain of undiagnosable abdominal pain for months. An initial threat or stimulus, like food poisoning, may have triggered pain signals. But even if the danger is gone—that is, the food poisoning has been resolved—the nervous system has become sensitized and therefore continues to send pain signals, prompted by smaller, nonthreatening triggers. The fire is out, but the fire alarm is still ringing.

Because pain is produced by the brain and the brain is shaped by our experiences, relationships, environment, past traumas, and more, pain can reflect not just what’s happening in the body but how safe or threatened the brain believes we are.

Drawing connections between our brains, bodies, and interpersonal relationships opens up some questions about faith and the nature of reality. How does your faith factor into your work?

My research and clinical practice are motivated by a desire to understand God’s creation, design, and vision for how our bodies are intended to work. All these things are done in pursuit of my ultimate goal, which is to know God. I am constantly praying for wisdom, asking the Holy Spirit to guide me in the larger arc of my work and in my moment-to-moment interactions with patients and clients.

Your research posits that if I think of pain as an exclusively physical phenomenon, I’m mistaken. It sounds as if pain emerges from a deeply relational, as well as material, place. This is interesting to me because we belong to a faith tradition that conceptualizes people as embodied spiritual beings. How have your findings interacted with your understanding of human beings?

I am continually in awe of God’s design. Our brain is a physical organ, yet it integrates information from our memories, emotions, and social contexts. This implies that something as complicated, intricate, and entirely physical as the brain is shaped by our individual lives, which then impacts our body.

Rewiring a brain that is on high alert requires strategic reengagement with the world. Regularly attending school, joining family game nights, spending time with church community, [and] receiving mental health support are all tools that can be effective for healing the brain. But the effectiveness of these tools is also dependent on culture, because people need to find forms of reengagement that make sense for them.

The research on relationships—peer relationships, familial relationships, and community—is also astounding. It highlights how much God has made us relational beings. Strong relationships can buffer the negative impact of pain while negative relationships can exacerbate it. In my clinical work, we’ve seen stunning progress in children and adolescents when we implement this type of “biopsychosocial,” or embodied, approach.

Your research isolates race and culture as factors that can impede or aid families and children in their treatment of physical pain. Why do you see these factors as significant?

Social dynamics, culture, and race all impact how we perceive, interpret, and respond to physical pain. This is much more pertinent in the case of chronic pain, during which the brain is continuously integrating external messages from our surroundings and culture to assess if we are still in danger and in need of protection.

In our research at Stanford, we saw different cultures and ethnicities exhibit different perceptions, experiences, and responses to pain. For example, Asian and Asian American children and adolescents do not fit into some of the existing narratives about how family dynamics can mitigate or exacerbate pain. There are two complicating factors: First, Asian youth usually report lower levels of pain, which has led mainstream medical literature to assume that Asian youth are suffering less. Second, parent behaviors that are typically believed to exacerbate chronic pain outcomes in white families—like allowing kids to receive special attention or miss school—do not lead to the same outcomes in Asian American families. Some kids and teens learn to rely on these accommodations, which can unintentionally reinforce pain-related sensations and behaviors. However, these accommodations do not have the same exacerbating effect in Asian American youth.

My hypothesis is that Asian American youth underreport pain due to stoic, collectivistic cultures and culturally specific dynamics in Asian American families cause behaviors that sometimes go against mainstream research. These are vast generalizations, but I’m working to understand these discrepancies by studying the relationship between cultural and physiological factors.

It’s interesting that your research points so concretely to our interconnectedness. The biblical narrative describes us as members of a single body, and again, to be frank, I often read this as pure symbolism—like an organizing metaphor for how I can think about my interconnectedness with other people. I rarely think about how our experience of our physical selves is so intensely shaped by one another. How does your understanding of the biblical narrative interact with your research?

My work gives me hope. In eternity, we will have glorified bodies where our nervous systems will not go haywire and misinterpret stimuli. My exposure to the work and my own experiences of chronic pain keep me aware that this is not where my body is to settle. It causes me to pine for eternity.

It also leaves me in awe of God’s redemptive power. Despite the brokenness of this world, he has equipped us with tangible, workable tools to rewire our brains and to relearn in a manner that is consistent with his beautiful design.

Finally, my research causes me to marvel at the diversity of people, communities, and cultures. Our bodies may be the same across time and culture, but they are profoundly shaped by the worlds we are nested in.

Yi Ning Chiu writes the newsletter Please Don’t Go. Previously, she was the columnist for Inkwell, Christianity Today’s creative NextGen project.