American Catholics are signaling a dramatic surge in concern about the persecuted church.

And prayer, alone, is no longer good enough, as more say money and arms are needed too.

Asked their opinion about Christian persecution worldwide in the fourth annual survey by Aid to the Church in Need–USA (ACNUSA), 67 percent stated they were “very concerned.”

Last year, only 52 percent said the same.

Similarly, 57 percent stated the level of persecution suffered by Christians is “very severe.”

Last year, only 41 percent said the same.

The increase is “heartening,” said George Marlin, ACNUSA chairman.

“Christian persecution around the world is very grave,” he said. “[Catholics] want both their church and their government to step up efforts to do more.”

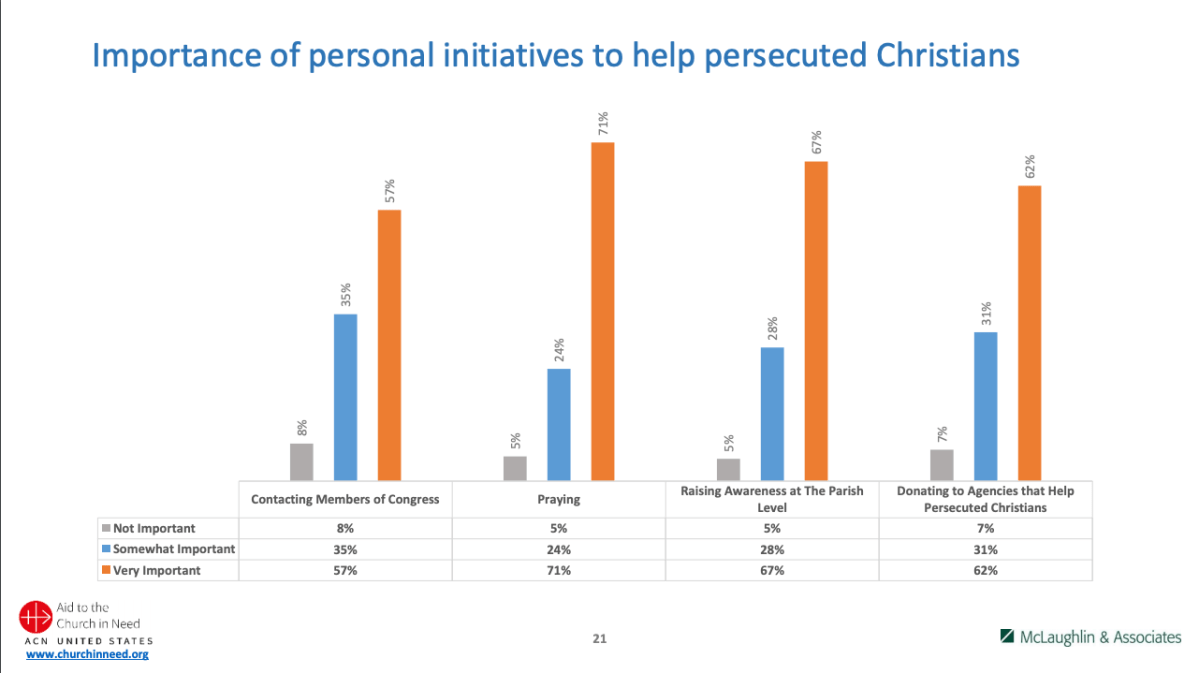

They have already been praying: 7 in 10 stated prayer is a “very important” initiative to help—the same share as last year, and up from 64 percent in the first survey in 2018.

But now, 62 percent say it is “very important” to donate to agencies that support the persecuted, up from 53 percent last year. Half say they are “very likely” to do so, up from 35 percent. And 61 percent say they gave within the last year, up from 53 percent in 2020.

And while about half believe Pope Francis is “very engaged” on the issue of persecution (52%, up from 47%), they believe their local bishop lags behind. Only 3 in 10 (30%) find him “very engaged,” marginally improved from the perception of 27 percent the year before.

The local parish seems to them similarly disconnected, with only 28 percent perceiving it to be “very engaged,” up from 22 percent last year.

It is not enough, per American Catholics: 2 in 3 said raising awareness at the parish level is “very important” (67%, vs. 59% last year).

Other church priorities have fallen a bit behind the persecuted.

The half of Catholics who said it is “very likely” they will give to church aid to the persecuted is matched by the 50 percent who will financially support missionaries. Commitments are lesser, though still strong, to donate toward church buildings (46%), Bible distribution (43%), and the training of priests (44%) and nuns (42%).

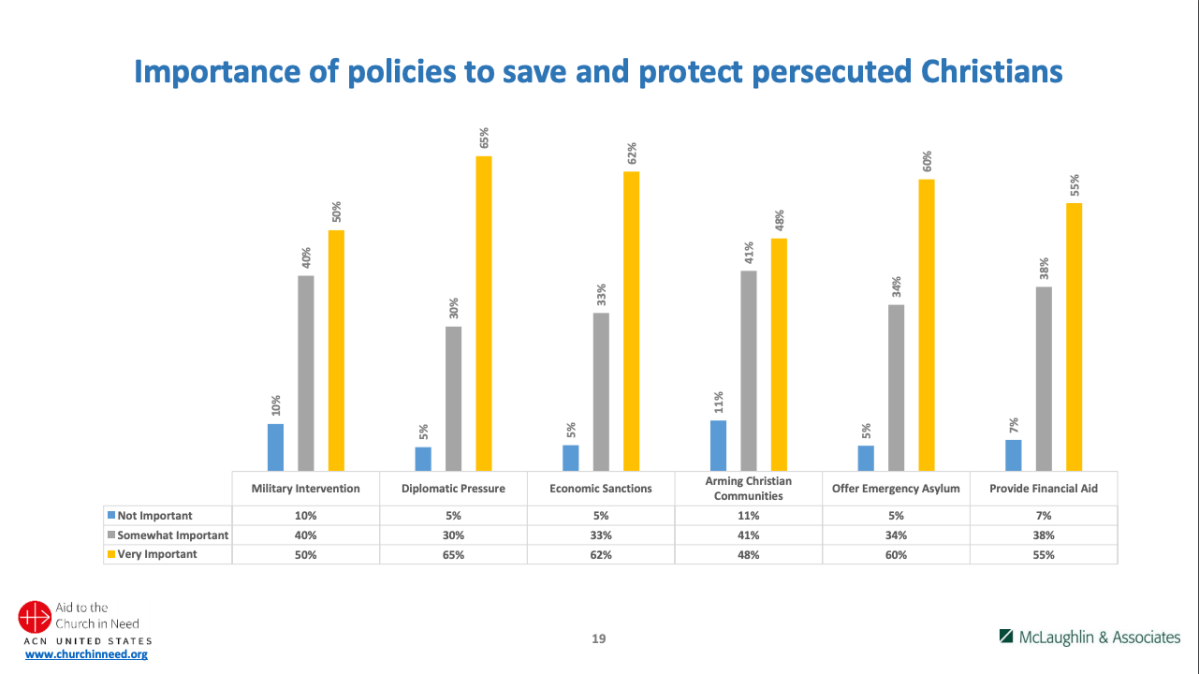

But as they desire the church’s concern, American Catholics also increasingly want Washington to help.

Diplomatic pressure on persecuting governments is a “very important” measure for 65 percent of Catholics, up from 55 percent a year ago. Economic sanctions are favored by 62 percent, up from 53 percent. Emergency asylum received 60 percent support, up from 52 percent, while 55 percent want the US to provide financial aid, up from 48 percent.

Militant options also grew in favor: Fifty percent said outside military intervention to protect persecuted Christians was “very important,” up from 46 percent, while 48 percent said the same for the provision of arms and training to communities facing genocide, up from 40 percent last year.

Harold John Ockenga’s distinguished career as a pastor, educator, administrator, and author has spanned more than half a century since his graduation from Westminster Theological Seminary in 1930. Upon completion of 25 years as chairman of the board of CHRISTIANITY TODAY, Dr. Ockenga reflected on some of his noteworthy experiences.

For 33 years he occupied the pulpit of Boston’s famed Park Street Church. His preaching and his leadership restored the church’s dynamic and brought new life to the cause of evangelicalism in New England. While there he set the pattern for world missions involvement that many churches have followed since. In the field of education, he was the first president of Fuller Theological Seminary and served in that capacity for 11 years. Most recently he was president of Gordon College and Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. His major contribution to the cause of evangelicalism in the U.S. and around the world came through his pioneering efforts on behalf of the National Association of Evangelicals and the World Evangelical Fellowship. The author of 14 books, he is retired and lives with his wife Audrey in Hamilton, Massachusetts. He will be 77 on his next birthday, but continues active in speaking and writing.

You started your pastorate at Park Street Church in 1936. How did you build up your congregation?

I put my hardest work on the Wednesday night message, because fewer people came to that service. I put my next hardest work on the Sunday night sermons because it’s harder for people to get out Sunday night, so you’ve got to have something interesting. I put the least work on my Sunday morning sermon, because I would get those people anyway. Incidentally, I got this idea from Dr. Withrow, who was pastor there years ago.

Did it work?

Yes. Things began to grow when I preached a series of Sunday evening sermons on “Our Protestant Heritage.” I took a number of different men—Calvin, Luther, Wesley, Zwingli, Cromwell, William of Orange. What I didn’t know then was that there were a lot of Orangemen [Irish Protestants] in New England. They must have gotten wind of what I was doing. They began filling up the church Sunday nights. From then on I had the evening congregation for whatever I preached. The morning congregation did seem to come in the evening.

You started the Boston Evening School of the Bible, too, didn’t you?

It ran for 25 years. There I taught something I had been working on for my sermons, so I could handle it without preparation.

But you still had to give four messages a week?

Yes, and then I added a fifth, the one on television on Thursday morning.

How did you find time?

I blocked out the whole week in half-hour segments, either for studying, or calling, or interviewing, or whatever. I worked hard and things began to grow. But then I got into trouble. We had no amplification system at that time and I began forcing my voice. I ripped a blood vessel in my vocal cords and was out for five months. But we turned the corner, and gradually got up to 2,400 members. It was a gradual, hard job. I used to wonder if I would ever have the crowds they had at Tremont Temple [a prominent downtown Boston church]. On Sunday night I’d look up and see 300 or 400 people and know that over there they had 2,400. I wondered what in the world was going on. But I worked and worked and worked, and finally it came. We had overflow congregations in the morning and were full at night.

Some people say that to do a really good sermon you have to work 20 hours on it. How did you do all the studying required for your sermons?

I did a lot of reading. I’d read on the subway going to church and home. I’d read at night. I’d even read some in my office. I had certain times for each thing I did. I always kept Mondays free, if I could; sometimes I visited people in the hospital on Monday. On Tuesday I started getting my topics ready for Sunday, if I didn’t have them in advance—which I usually did. I’d get those topics ready, get the material ready for the church bulletin, and that sort of thing. Then I would work for my Sunday evening sermon. That was the last thing I would unload, so I did it first. I’d work on that until late afternoon, and then go calling.

Wednesday morning I’d start on the Sunday evening sermon again and pretty much finish it up. At noon I’d go to the Rotary Club, and on Wednesday afternoon I had interviews. Wednesday night I’d have some meeting of the church, or be out somewhere.

Thursday morning I would start on my Sunday morning sermon. In the afternoon I’d go calling. Because our midweek meeting was Friday night, I would put everything aside on Friday morning and work on that topic until I got through. Then I’d do organizational work.

On Saturday morning I would go back to the Sunday morning sermon and work on it until I got done. I never worked at home. I always went to my office and I stayed there until I was finished with the morning sermon. Because I had to unload that first I put it in last, making it the freshest in my mind.

Sunday afternoon we would go home, have dinner, and a nap. Then I would get up and work on my Sunday evening sermon to get it in mind. I wrote out my sermons and memorized them, and always preached without notes.

Tell us about your reading.

I try to read a book a week, something I have done for years. Everywhere I go I take books. I have long-term reading, where you can go through a whole book, like on a plane trip to California. And I have short-term reading, when you have 15 or 20 minutes, like standing in the subway. I read at night. On Monday I’d go off somewhere, or I’d stay at home and read or work outside.

Over the years, what books have been crucial building blocks, or just something special to you?

Someone asked me to list the 12 most important books I had read. This is my list: What Is Christian Civilization?, by John Daley; Crisis of Our Age, by Pitirim Sorokin; What Is Christianity?, by Herbert Butterfield; What Is Faith, by J. Gresham Machen; Therefore Stand, by Wilbur M. Smith; The Battle for the Bible, by Harold Lindsell; How to Be Born Again, by Billy Graham; Fire in the Fireplace, by Charles Hummel; On Human Understanding, by John Locke; The Communist Manifesto, by Karl Marx; and The World and the West, by Arnold Toynbee.

Do you agree that preaching is the basis of the pastor’s authority?

One hundred percent. You can’t stand and converse with people from the pulpit; you’ll lose them. If you have a strong pulpit ministry, you’re going to have a strong church, no matter if everything else is lacking. If you have a strong counseling church without a strong pulpit, you’ll have a weak church. Preaching has got to be there, or people are not going to come. It has to be enlightening, interesting, and challenging. Conversational preaching is a mistake. You’ve got to develop certain points, like a syllogism. You have to develop something people can follow, an outline with alliteration. When you get through, people can say, “That’s what he said about this and that’s what he said about that.”

Is there too much of an emphasis today on the pastor as a teacher rather than as a preacher?

The pastor-teacher is the essence of the pastor-preacher. A man can’t preach two or three times a week without teaching. He has to have content. One fellow once told me, “I never thought content would be the attractive power of the pulpit until I went to hear you. The thing that brought me back always was the content.” I preached through books of Scripture. This was not running comment—I preached: 30 or 40 sermons on a book of Scripture. The people would come back; they would want to hear the next one and the next one. We didn’t have any advertising. It was preaching that filled the church.

What really distinguishes the preacher from the teacher?

I’ll tell how I learned the difference. When I was in college, I preached one whole summer as part of an evangelistic team. Later I was asked to preach again in one of those churches. In the meantime, I’d had a religious experience, so I took the Scripture and illustrated it by that experience and applied it to the people. When I got through, one of the members of the team came to me and said, “That’s the first message I’ve ever heard you give.” The difference is, you’re pouring out your soul to get something across. You must have urgency. You want to move people so they will act and respond.

You mentioned strong counseling ministry without a strong preaching ministry. Some pastors are spending 20 to 30 hours a week counseling. Is this a good trend for the church or not?

It’s a cop-out from able, dedicated preaching. Pastors are glad to do it because they don’t have to prepare for it. They don’t have to do anything but sit and listen to people, and then give them their best advice. In some cases their advice may not be good, because they’re not trained well enough. I never got any counseling from anybody in my life; maybe one or two cases, but that’s all.

You did no counseling as a pastor?

I always had a counseling period. Wednesday afternoons when people could come and interview me were always full. But I’d go home tired and unsatisfied with the whole thing. It’s dirtying to listen to these things. I just don’t think that is what the Lord wants us to do. If your preaching is biblical, people will get the same ideas you give in counseling. You might as well handle a thousand people as one or ten. Counseling takes time. You can’t do that and preach.

How did you handle the growing pains at Park Street Church?

What discouraged me the most was that the New Englanders thought differently than people elsewhere. In the Midwest, South, or West, if a preacher has an idea and he wants to put it across, he can put it across. I’d have to suggest it, and suggest it. Then I’d have to let it sit for four or five years until somebody else thought it was his idea and he advanced it. Then we would be able to do it.

Do you recall any really hot controversies?

We used to keep quite a large sum in reserve for emergencies—like bringing missionaries home, or to use if the church burned down. It was 0,000 or 0,000. We were supporting 145 missionaries. Well, one of my men got the idea we ought to spend everything. We had a knock-down, drag-out fight one night in the board of deacons. I told them that as long as I was pastor, I was going to have the say as to where we spent our money. He finally came around, but it wasn’t easy.

Another time two of our trustees were at loggerheads over our investment policy. So I got the trustees together one night and said, “Look, men, we’re having a lot of blessing in this church. It would be easy to lose it all if you start fighting. Now, either you can tell the board that you’re sorry you have put these things in one another’s way, or you can both leave. One or the other, but we’re not going on with this anymore.”

One fellow got up like a gentleman and said, “I apologize to you. I’ll not insist on my way any longer.” The other fellow sat there, glum as an ox, and finally he said, “Well, I’m not going to change.” He left and never came back.

How did you develop your interest in missions?

When I was a student at Princeton, I volunteered to be a missionary. I was planning to go to China. One day Clarence Macartney and some other prominent preachers got hold of me and said, “Look, we’re not going to be able to do anything for missions if we don’t hold some of these churches in this country. You ought to take a church here, build it up, and raise money for missions.”

That’s what I did, first with Macartney at First Presbyterian, Pittsburgh, then at Point Breeze, and then at Park Street. I tried to put missions first at the time. The first year I was at Park Street we had ,200 for missions. We soon changed that. Missions were first in our interest—in our giving, and everything else. We did it by voluntary giving. We never raised any money with chicken pot pie suppers.

You’ve raised a lot of money in your time. What insights do you have about money management in the local church?

The pastor should sit on the board of trustees, not as a member, but just as he should sit on the board of deacons, or elders. He ought to know where everything goes. He has to raise the money, therefore he ought to be able to see where it goes. He ought to be able to agree with where people want it to go. But if it is raised for one thing, don’t take it from that for something else.

He ought to have a good bit to say about the final disposition of funds. I didn’t do that directly; I did it through the boards. I sat on every board that spent a dime, because I didn’t want the money to go to the wrong place. It was too hard to raise.

While you were pastor at Park Street Church you were also president of Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, California. How did you handle both responsibilities?

I commuted a great deal and used the telephone a lot. I guess I went back and forth 200 times. I used my assistant, Harold Lindsell, a lot. He executed what I determined as policy—with the trustees, of course.

You were also president of the National Association of Evangelicals for a while and chairman of CHRISTIANITY TODAY for 25 years.

I have always been very busy, but there is a secret to that. You can do things okay if you keep a prayer list. I’ve kept one for 41 years and I have everything on that list. When I go over it, I’m reminded by the Lord if I haven’t tried to solve a problem; I’m very alert to that situation. If I have enemies I’m praying for, something may come to my mind that I can do about that.

Everything goes on that prayer list: faculty, evangelism, family. I write a very brief summary of what the petition is, and I number it and date it. When it’s answered, I write across it “answered.” As I pray, I don’t look at those, I just go to the next one. Some have been answered in the negative—not very many, but some of them. I just put crosses right across those, and I know immediately that they have been denied. This keeps a person alert to his responsibilities.

For instance, if I had a problem at Fuller, I put it on the prayer list. When I would go over the list I was reminded of that problem. I either prayed about it or did something about it that needed to be done. That was a way to keep alert to administrative activities so I could run Fuller, the NAE, CHRISTIANITY TODAY, and my church.

This gives you a tremendous release from tension. When do you find time to pray?

That’s right—I never worry about it. I pray every morning. First I do my exercises, then shave and bathe, then pray until my wife has breakfast ready. I pick up where I left off on my prayer list and go on through the whole thing. I’ve had this prayer habit from the time I went to college.

Speaking of your college experience, it’s been said that you are the heir of a blend of Reformed and Wesleyan traditions. Is that how you would describe yourself?

There’s some truth to that. I went to Taylor University from a large Methodist church in Chicago. There I came under the influence of the holiness club. I felt I needed another, or deeper, Christian experience. Things weren’t going well on the evangelistic team. I was going to quit preaching, but one of the fellows told me I was the trouble.

One Sunday morning one of them preached on Acts 1:8, “You will have power, after that the Holy Ghost has come upon you,” a sermon I’d heard him preach before. He gave the invitation and nobody responded. As we came to the last stanza, it was as if somebody spoke to me out of the blue, “You want that bliss …” I went forward and it has made the difference in my life. I recognized that I needed a different quality of experience through the Holy Spirit, which I didn’t have at that time. I told the Lord I wanted it.

I found out that there is a higher standard than just being a believer. There is such a thing as being filled with the Holy Spirit for a purpose. The Lord does that.

So, I got the Wesleyan emphasis at Taylor. I rejected sanctification in the sense of being without sin. I left Taylor and went to Princeton. Then I went to Westminster and more or less absorbed the Reformed and Presbyterian viewpoint. But I think there is a lot of the Methodist in me when it comes to preaching.

Your pastoral ministry was also an interesting blend of a large major denomination and a smaller one. How do you compare the two?

I started pastoring a Methodist church in the summer resort town of Avalon, New Jersey, during my last year at Princeton. The people wanted me but the bishop told them I had gone to the wrong seminary; it wasn’t Methodist. In the meantime, Clarence Macartney had invited me to be his assistant at First Presbyterian, Pittsburgh. But I stayed in the Methodist church for a year until the annual conference. Out of the blue, Macartney wrote me again. I decided to test the people at Avalon over the summer. That’s when everybody makes money, but they don’t go to church. The summer went by and I didn’t see any of my faithful people until September. So I decided to accept Macartney’s offer.

I joined Chambers Wiley Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia, was licensed by the Philadelphia presbytery, and then transferred to the presbytery of Pittsburgh. I became a Congregationalist the minute I went to Park Street Church. I was installed by the Congregational Church. I held standing in both denominations. The Pittsburgh presbytery had me laboring outside the bonds of the presbytery and the Suffolk West Association (Congregational) accepted me as a member of their association.

Didn’t you subsequently leave both denominations?

The Los Angeles presbytery didn’t want Fuller seminary there. Half of our students came from local Presbyterian churches, and in ten years we would have controlled that presbytery and several others if they would have given us the green light. They asked my presbytery to enjoin me from laboring out there. I was told I could fight it, and probably win, but the seminary would have been launched in a controversy, so I didn’t.

When the Congregational Church merged with the Evangelical and Reformed Church (to form the United Church of Christ), they allowed those who didn’t come in—many churches like Park Street didn’t—to have their names published in the annual minutes. I still have my name there, although I am not a member of the United Church of Christ.

A Pulpit Primer

While serving as Dr. Ockenga’s student assistant at Park Street Church in 1937, I made my way to his tower study after a Sunday morning worship service. Intrigued by his sermon content and flawless delivery, I asked, “Dr. Ockenga, could you take time to explain to me your method of sermon preparation and delivery?” Without hesitation, while he showered and dressed, he launched into a homiletical lecture and study that surpassed all the college, seminary, and graduate speech courses I ever had.

It revolutionized my own preaching style. It challenged me to prayerful subject selection, thorough biblical research and preparation, careful word-for-word manuscript writing, detailed and comprehensive sermon outlining, memorization of the sermon outline, and utter dependence upon the Holy Spirit for preaching without notes.

Little did I realize that this impromptu lecture by one of America’s greatest pulpiteers was God’s crash course preparing me for Dr. Ockenga’s brief illness. In a few months (as a young theolog) I was preaching in his strategic Boston pulpit. It also became my model for over 40 years of teaching and preaching.

JOHN A. HUFFMAN, SR.

Dr. Ockenga’s First Assistant

Park Street Church

Should a young candidate for the ministry start in one of the major, liberally oriented denominations, or in a smaller evangelical body?

It depends on the individual and his background. If he’s a member of a smaller denomination, he’s got to consider the cost. On the other hand, if he’s a member of a big denomination, United Presbyterian or Methodist, he should stay there, preach, and bear his testimony, unless he’s hindered and limited by the denomination. If it becomes an issue of doctrine or principle, then he has to leave.

How can one prepare for ministry in a mainstream denomination?

Get your evangelical theological training first. Go to an evangelical seminary first, so you have the answers to the problems liberals raise. If you go to a liberal seminary first, and they raise the problems and you have no answers, you’re set adrift. Get your positive answers first and you can judge what you would like to do.

You can always go from a big denomination to a little one, but you can’t go from a little one to a big one. They raise too many questions. They press too hard on you. They have their own students trained in their own seminaries and they want them to have the jobs.

What do you think about the church growth movement?

It’s almost a fetish. I used the good things in the church growth movement before there was a movement. Some of the ideas are good. Get the head of a family converted first and the family probably will come. Get the leader of a group and you probably will get the people. But I don’t like some of the viewpoints, especially the one about making converts all of one class [homogeneous unit principle]. Supposedly, if they were all of one kind, your church could grow much more rapidly than by having converts of diverse backgrounds. Obviously, such churches will grow faster. People are much more at home in a group like that. But that’s not what the church should be. The New Testament church at Antioch, for example, had wealthy and poor people, educated and uneducated, blacks and whites. The church should cut across these things, so people feel at home in other than their own culture or class.

Take Park Street Church. We always had some wealthy people; not many. We had a great many poor people, a great many blue collar workers. Our deacons and trustees represented all classes of people. The wealthy ones didn’t look down on the others. The middle-class people didn’t demand that we put people from their group in office.

You were instrumental in the founding of the National Association of Evangelicals, were you not?

In 1936, J. Elwyn Wright conceived the idea of a national organization. He said that if we didn’t do this, we’d be frozen out by the Federal [later National] Council of Churches. I wasn’t quite convinced, but I went to the first meeting in Saint Louis. We met for a week, about 150 or 175 men. Wright asked me to give the keynote address (published in Great Speeches that Affected America). I told them we had to get together, to stand together. We had to do it in radio broadcasting, or we would be put off the air. The Federal Council was drawing up a broadcasting code of ethics. We had to do it in the military, or we wouldn’t have any chaplains. The impetus for NAE came from the fact that the fellows all felt they were being cut down.

At that time Carl McIntire demanded that we state categorically in our constitution that we were opposed to the Federal Council, and that our purpose was to hinder their work. It wasn’t the right thing to do, because we would have started on a negative rather than a positive basis. McIntire forced a vote on the issue and lost, but he pulled out 25 or 30 fellows with him and later they formed the American Council of Christian Churches. We went ahead and laid down our basic principles and formed the NAE.

They made me president—because I made the speech, I guess. The church permitted me to make three major trips across the country to speak in churches about the NAE and what we were going to do. Finally, in 1943, we met for a solid week in Chicago for our constitutional convention. We had a great time. I remember Bishop Leslie Marsden of the Free Methodists saying as we were leaving, “America’s revival is breaking.”

How did things go between you and McIntire?

You should know that Carl was in my wedding party, but when I refused to join the Independent Board for Foreign Missions of the Presbyterian Church, he was so disgusted that he returned the gift I had given him, a couple of book ends of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. Anyway, when he started his American Council it became very confusing for churches, schools, missions boards, and denominations. Rather than get into the scrap, many of them decided not to join either NAE or the ACCC.

But the ACCC did a very bad thing. They would home in on an individual, publish the reports in McIntire’s Christian Beacon, and undermine his work. They cut into his invitations. They went after Donald Barnhouse, after me, after somebody else. They began to whittle us down, one by one, who were the leaders of NAE. As a result, some of them dropped out. It was unfortunate that we had the ACCC and NAE division.

What dangers do you foresee for evangelicals now?

One of them is fragmentation. It looks like it might be over the question of inerrancy of Scripture. That could be a divisive thing when it comes to the future of NAE. However, I think that denominationally we’ve almost had all of the fragmentation we’re going to have. If NAE stays with a positive emphasis, it can have a great influence in the churches.

“In the secular media, there is still not enough coverage,” Joop Koopman, ACNUSA director of communications, told CT, speculating on the reason behind the increases from the 2020 survey.

“But in Catholic media, the news is out there, and I believe the effect is cumulative.”

The parish bulletin is the most trusted source of Catholic news, according to the survey, while CNN is most favored for secular news.

So while the ISIS-led persecution of Middle East Christians has faded from immediate memory, Nigeria and India have captured Catholic attention. Also significant, Koopman said, was this month’s visit of Pope Francis to Iraq.

Though the survey took place in February, just before the trip, there was significant media attention on the preparations and highlighting the nation’s declining Christian population.

Overall, American Catholics identified China, North Korea, and Pakistan as the worst persecutors of Christians today. These nations rank No. 17, No. 1, and No. 5, respectively, on Open Doors’ 2021 World Watch List of nations where it is hardest to follow Jesus.

China has received much attention from the Vatican as it negotiates the recognition of bishops in the underground church. A 2018 deal was controversially extended last October, against objections by the United States.

Catholics once represented a substantial portion of North Korean Christians. And Asia Bibi, a Catholic, attracted worldwide attention over her death sentence for blasphemy before being acquitted in 2018 and fleeing Pakistan one year later.

But according to ACNUSA, American Catholics lack awareness of many details:

- Only 41 percent know that being a Christian in North Korea can warrant the death penalty.

- Only 37 percent know of the abduction of underage Christian girls in Pakistan, who are then forced into marriage and converted to Islam.

- Only 35 percent know that Mass attendance in China is subject to digital surveillance.

- Only 36 percent know of the thousands killed for their faith in Nigeria.

- Only 28 percent know of the hundreds of incidents of persecution in India.

And less than half (46%) correctly identify Christians as suffering half or more of religiously based attacks around the world. Researchers with Under Caesar’s Sword, a $1 million Templeton Religion Trust study, found that Christians experience 60–80 percent of the world’s religious discrimination. (More of it is experienced by evangelicals than by Catholics.)

Even so, that 9 in 10 American Catholics who find overall Christian persecution at least “somewhat severe” has stayed steady since 2018.

“The poll shows the great need to inform the public regarding specific instances of Christian persecution,” said Marlin. “US bishops and organizations like our own must step up our educational efforts.”

Devotionally, however, the church has been more successful.

Almost half of American Catholics (48%) now label themselves as “very devout,” up from 42 percent last year and 38 percent in 2018. Only 13 percent today say they are “not devout.”

But church attendance has not kept up with the trend. Only 38 percent attend Mass weekly, though that’s an increase from 33 percent last year.

The increase in reported devotion is accompanied by a shift toward the Democratic Party. The 28 percent who called themselves Republican has held steady since 2018. But the third who called themselves Independent or “other” has declined to a quarter, while Democratic identity has increased to 47 percent, up from 39 percent.

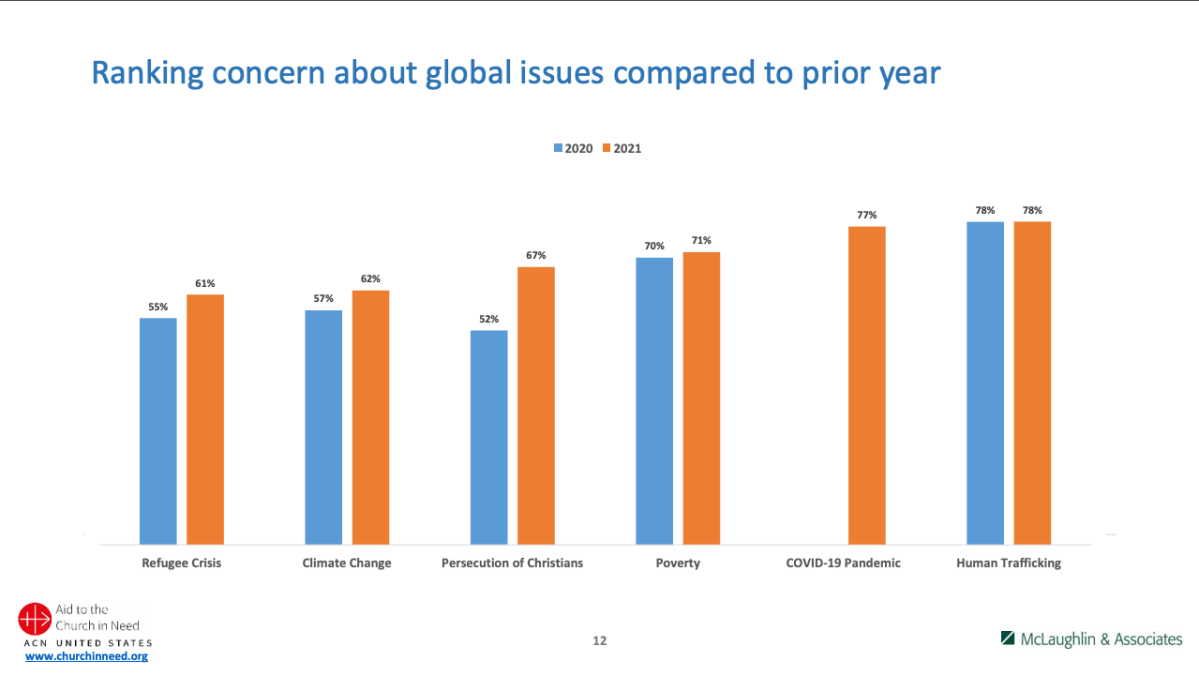

And while the percentage of American Catholics “very concerned” about persecution has dramatically risen, it still falls behind other global issues.

Parachurch youth ministries are gathering them up where mainline denominations began dropping them a decade ago.The dinner party included some of the cream of the leadership of a major Protestant denomination. Present with their spouses were two professors from a nearby seminary, three denominational executives, and the president of a church-related liberal arts college.Most were Democrats. They were appropriately committed to massive governmental programs to solve social problems, and to church involvement in the process. They were concerned about world hunger. They shared an intellectual commitment to a simpler lifestyle (“Live simply that others may simply live”) and had somewhat guilty consciences about their own affluence. They deplored the exploitation of Third World countries by multinational corporations, and generally approved various liberation theologies. They were scornful of conservatives in the denomination who accused the World Council of Churches of fostering Marxist movements.They deplored the “narrowness” of the group of evangelicals now in control of the Student Christian Association on the college president’s campus, and the lack of interest in religion on the part of the majority of students. They shared the frustration of the seminary professors at having to cope with the increasing conservatism of each incoming class, and laughed as one of them jested that they seemed to be training the future leadership of the Orthodox Presbyterians and the Conservative Baptists.Then the hostess got a telephone call from her teen-aged son, who was attending a meeting of Young Life. The conversation turned to Young Life, and the fine young man who headed up the program in the local high school. The host couple had two children involved, and they were delighted with what was happening. Another couple, one of the seminary professors and his wife, reported that their two sons were also deeply involved in Young Life in another high school in the city. They, too, were pleased about it; the wife wondered with pardonable pride how many mothers had sent two sons off to summer football camp, both with their Bibles packed on top of their sleeping bags.One of the denominational executives began to talk about the absence of any kind of solid content at the parish youth fellowship his kids attended; it seemed to be largely recreational. Another deplored his inability to get his kids to participate in his congregation’s youth program at all, although he admitted it was so inconsequential and poorly attended that he couldn’t blame them. He recalled the significance of his own church youth group experience when he was growing up, the familiarity with the Bible that came out of his Sunday school attendance, and the spiritual intensity of his adolescent religious experience. He frankly—and sadly—saw nothing in the parish where he and his family were involved that could provide anything similar for his own children. And he wished his kids would join Young Life!Major Denominational Youth Programs: The SixtiesThese dinner party guests were leading establishmentarians. Nothing could more vividly portray the youth dilemma in the churches of the so-called mainline denominations than their conversation. Where have all the young folks gone? Mainly to Young Life, or Youth for Christ, or Campus Crusade, or Inter-Varsity Christian Fellowship, or the Sunday evening program of a nearby Southern Baptist church. Or else nowhere. Mainline Protestant parish youth programs, with some notable exceptions, are moribund. Mainline campus ministries play to empty halls. Mainline denominational youth ministry bureaucrats, by and large, are still hooked on the greening of America.This is our heritage from the sixties. Nowhere in American society did the youth countercultural values of that decade receive a more sympathetic hearing than in mainline churches. And for understandable reasons. The idealism, the activist involvement, the commitment to radical change—all these the mainline groups applauded. We marched alongside the counterculture in the civil-rights movement, and the anti-Vietnam War movement. We had a common cause. Draft card burnings nearly always featured a William Sloan Coffin or Dan Berrigan right up in front of the TV cameras. Youth was the “cutting edge.” Innumerable religious retreats plumbed the theological profundity of Beatles’ songs (especially “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” the tunes of which can still bring on an attack of acute nostalgia for anyone who, like me, was working with young adults during that period).Many of today’s mainline denominational executives cut their teeth on the counterculture. Radical protest was the norm of their formative years. Today they find a newer generation of young people to be baffling and unsettling, success oriented, nonprotesting, traditional in values.Another major influence on their own spiritual formation was the human relations movement, which also reached its peak in the sixties and early seventies. Its groupiness, its “touchy-feely” games, its self-discovery and self-affirmation, its simulation and trust-building exercises were the “methodologies” of the period. The fact that they were all methodology and no theology seemed irrelevant at the time. It was a compliment in human relations circles to be called “process oriented,” an insult to be known as “content oriented.”Major Denominational Youth Work TodayThe above picture may be overdrawn, but it is accurate enough to have affected significantly the current shape of youth work in these mainline denominations. The counterculture is dead, except as the context for denominational youth programs. Campus ministry, especially, has provided it with a last bastion. Mainline campus ministries are often isolated from parish life and accountable only to ecumenical bureaucracies far removed from and independent of either the university administration or the people in the pew. Yet they are still trying to fan the embers of radical protest. And local church youth groups are all too often still playing the trust games or engaging in “value clarification.” Church members, by and large, do not understand what is wrong with youth programs in their congregations, and they are not sure what should be done to fill the vacuum. But they know a vacuum exists, and they want something done about it. No concern is higher on their agenda, as they press church hierarchies for action.Whatever the answer for mainline churches may be, many young people have not waited for their parents, or the young associate ministers who run the programs in their parishes, or their denominational bureaucracies to find out. Vast numbers of them have found theft own answer outside the mainline churches, in the evangelical, nondenominational youth movements.Evangelical Youth MovementsMost of the major evangelical youth movements antedate the sixties, but their greatest impact on mainline young people has come since the sixties. Bible study is their stock in trade. They work through young, dedicated, full-time staff workers, who are often required to raise theft own salaries. And in contrast to moribund denominational youth programs, these movements are flourishing.At the high school level, the largest is Youth for Christ. It operates campus-oriented evangelistic teen clubs at well over a thousand American high schools. Young Life is also a high school (and sometimes junior high) movement, with something over a thousand clubs. In addition, it operates weekend and summer camps. It has recently added an urban Young Life operation for inner-city teen-agers, mostly black, with an emphasis on justice and jobs as well as on its usual spiritual concerns.Campus Crusade is by far the largest and most aggressive of the evangelical youth organizations. It is probably the most conspicuous Christian organization on college and university campuses, and it has branched out into a number of other specialized youth and young adult ministries. It has a high school branch, and an extensive ministry to young adults in the American armed forces all over the world.Inter-Varsity Christian Fellowship has chapters on over 800 American campuses. They are student-controlled, although IVCF does have staff personnel. Its style of evangelism is lower key and considerably less aggressive than that of Campus Crusade, and its lifestyle expectations are less legalistic. Inter-Varsity is well known for its Urbana (University of Illinois) missionary conventions. Urbana ’79 undertook to motivate at least a thousand young people a year to enter overseas missionary service for the next five years. The majority attending were from mainline churches, the largest single group being United Presbyterians with 1,104 delegates.Another predominantly youth-oriented organization is the Navigators, which originated as a movement among enlisted men in the navy during World War II. In recent years Navigators has expanded its ministry beyond the armed forces to other young adult communities, primarily college campuses. The Fellowship of Christian Athletes is an organization of athletes and coaches banded together to influence young people. It sponsors high school “Huddles” and college “Fellowships.” Coaches’ clinics, rallies, and banquets are all widely used in a ministry aimed at personal evangelism.Although these are the best known, they are by no means the only evangelical youth and young adult movements. Collectively, the independent evangelical youth organizations are by far the most significant and influential Christian youth movement in contemporary American society. Theft influence, however, is reinforced from other sources.Christian Academies And CollegesMy young teen-aged daughter reported recently that she “can’t stand” the superiority of one girl in her Sunday school class, whose one-upmanship consists of frequent reminders in class discussion, “Of course, I go to a Christian school.” The Christian academies found in most cities are almost without exception evangelical in orientation, and frequently they represent the fundamentalist wing of evangelicalism. At the end of the seventies, between 700 and 800 new private Christian elementary schools or high schools were being launched each year. More than five-and-a-half million students are currently enrolled in private elementary and secondary schools, two-thirds of them in Christian schools.What is widely perceived as a decline in the public school system with its emphasis on social goals, the “professionalization” of the educational establishment, the succession of educational fads (“progressive schools,” “whole-child” and “child-centered” emphases, “existential” education, “open classrooms”), the demise of discipline, and the widely documented decline in standard achievement and SAT (Scholastic Aptitude Test) scores, all have led many to seek alternatives. The traditional upper-class private schools are largely for the rich. The Christian academies, which frequently have higher academic standards than public schools, have provided the only real alternative for the not-so-rich, including many liberals from mainline groups.The evangelical colleges provide a continuation of the same educational influences at a higher level. They are unlike the Christian academies, to which many children are sent for reasons unrelated to evangelical orientation by parents seeking discipline and academic emphasis; the evangelical colleges are usually chosen explicitly for their religious stance. Parents distrusting the secular scientific world view, and the absence of constraint in the student environment of secular universities and the liberal mainline denominational colleges, have chosen evangelical colleges for their children. Young people of evangelical convictions have chosen them for themselves.Attitudes And TrendsReports from nondenominational evangelical youth organizations, Christian academies, and evangelical colleges are not the only source of data on what is happening to young people of mainline churches. The Princeton Religious Research Center, which bases its reports of religious trends on polls conducted by the Gallup organization, reports that the evangelical movement is strong among the nation’s youth. Evangelical gains, “often at the expense of mainline churches,” according to the center, are evidenced by the high percentage of teen-agers (44 percent of those identifying themselves as Protestants and 22 percent of the Catholics) who say they have had a “born again” experience.Similar evidence came from a Religious News Service tum-of-the-decade report on increasing interest in religion among college students in the second half of the seventies. The RNS survey saw the trend as conservative, pointing to such indications as the growing popularity of religion courses, with the addition of such courses and of departments of religion by responsive administrations, increasing attendance at religious assemblies, and growing willingness to voice religious opinions in class.The report noted the popularity of informal Bible reading or study groups in dormitories. Military chaplains have also observed a striking increase in such Bible study groups in barracks, camps, and ships. The Princeton Religious Research Center reported that 33 percent of Protestant teen-agers and 20 percent of the Catholics say they are involved in Bible study groups.The Princeton Center sees one of the characteristics of youth in the dawning eighties to be a return to traditional values. Except for marked differences on certain social issues (acceptance of the use of marijuana, and sexual freedom), the study found remarkably little difference between the attitudes of teen-agers and college students on one hand, and those of older Americans on the other. This shows a marked swing toward traditional values.These findings were further confirmed by a 1979–80 survey of students listed in Who’s Who Among American High School Students. It identified a decidedly conservative trend among high school leaders. Though religion has always played a significant role in the lives of this particular group, a striking 86 percent in this survey said they belonged to organized religion, up sharply from 70 percent in the 1969–70 poll 10 years earlier. Three-quarters said religion was an important part of their lives, and 67 percent claimed to have chosen their religious beliefs after independent personal investigation.What are young people looking for? All too often the liberal mainline establishment envisions them as seeking channels for idealism, for protest, for action aimed at bringing about social change. The youth counterculture of the sixties and early seventies, Christian and secular, was indeed seeking such channels. But it is questionable if even then a significant number of young people were seeking such channels to express a distinctively Christian idealism. Today’s social activists in the mainline church establishment are, by and large, responding to a Christian dynamic. Their meaning structure is a deep faith, acquired often in a more conservative church environment in their youth. But the generation they have produced in mainline churches, where attention is fixed on social change, lacks that rooting in a deep faith. Members of this generation are finding the meaning structure the seek in the evangelical youth movements, the evangelical colleges, and in a turn toward traditional values and conservative religion.All these reflect the theological stance of evangelical Christianity. Thomas C. Oden, a mainline seminary faculty member who refers to himself as a reformed liberal, speaks of “postmodern orthodoxy.” He says: “The sons and daughters of modernity are rediscovering the neglected beauty of classical Christian teaching.… They have had a bellyful of the hyped claims of modern therapies and political messianism to make things right. They are fascinated—and often passionately moved—by the primitive language of the apostolic tradition and the church fathers, undiluted by our contemporary efforts to soften it.… Finally my students got through to me. They do not want to hear a watered-down modern reinterpretation. They want nothing less than the substance of the faith of the apostles and martyrs.”Significance is generally ascribed to trends among young people in terms of what they foreshadow for the adults of tomorrow. A fairly clear picture seems to be emerging. Many of our youth have left us. They no longer see the church as a meaningful part of their lives. But a significant part of those still with us are young evangelicals. In 1979 the general assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the U.S. began for the first time to record the results of a straw vote of the Youth Advisory participants alongside the official action of the commissioners. On a surprisingly large number of issues with an identifiable “conservative” and “liberal” side, the youth vote has been more conservative than that of the adults. Some of these evangelical young people are being shaped in our own congregations, particularly those congregations that make up the evangelical wing of the mainline denominations. But many are finding their meaning structure elsewhere.Youth for Christ, Inter-Varsity, Christian academies, and nondenominational evangelical colleges are all now playing a part in shaping the new generation in the mainline churches.Nowhere is the future leadership of the church more clearly foreshadowed than in the seminaries. It was the seminaries of the fifties, sixties, and seventies that nourished today’s leaders on a diet that progressed from Barth to Bonhoeffer to Bishop Robinson and Harvey Cox to Gustavo Gutierrez. If denominational seminaries seemed too confining to earlier generations, the more adventurous went off to interdenominational Yale, Harvard, Union, Chicago, or perhaps to Berkeley. Now the more adventurous are forsaking denominational seminaries to go in the opposite direction. They are going to Fuller and Gordon-Conwell. The largest Presbyterian seminary in the world (in terms of the number of Presbyterian candidates for the ministry enrolled) is Princeton. But the second largest is Fuller. And third is Gordon-Conwell.Further, there is evidence that students in the mainline denominational seminaries are coming from conservative backgrounds. Those seminarians whose sense of calling has been nourished in their home churches are coming from the evangelically oriented mainline congregations.A 1979 study of candidates for the ministry within my own denomination, the Presbyterian Church in the U.S., showed that 44 percent of all candidates came from just 82 congregations—2 percent of the PCUS congregations, with 10 percent of the membership—and that most of these were known as conservative congregations. Student bodies are more and more evangelical. The seminary professor quoted earlier as saying his seminary was training the future leadership of the Orthodox Presbyterians and Conservative Baptists was dead wrong; it is training the evangelical future leadership of his own mainline denomination.There are some indications that mainline denominations may be getting the message, and that a genuine renewal of youth work may be developing. The early eighties have seen a spontaneous movement among many mainline groups in the direction of the recovery of a pattern of an earlier day with the reemergence of youth councils, youth rallies in local areas, and a growing call for denominational resources with Christian content, rather than just methodology. Whether a real recovery of mainline youth programs is on the horizon remains to be seen, but early signs are encouraging.Meanwhile, however, the wave of the future is already upon us. Where have all the young folks gone? They’re over at Young Life, studying their Bibles.

Parachurch youth ministries are gathering them up where mainline denominations began dropping them a decade ago.The dinner party included some of the cream of the leadership of a major Protestant denomination. Present with their spouses were two professors from a nearby seminary, three denominational executives, and the president of a church-related liberal arts college.Most were Democrats. They were appropriately committed to massive governmental programs to solve social problems, and to church involvement in the process. They were concerned about world hunger. They shared an intellectual commitment to a simpler lifestyle (“Live simply that others may simply live”) and had somewhat guilty consciences about their own affluence. They deplored the exploitation of Third World countries by multinational corporations, and generally approved various liberation theologies. They were scornful of conservatives in the denomination who accused the World Council of Churches of fostering Marxist movements.They deplored the “narrowness” of the group of evangelicals now in control of the Student Christian Association on the college president’s campus, and the lack of interest in religion on the part of the majority of students. They shared the frustration of the seminary professors at having to cope with the increasing conservatism of each incoming class, and laughed as one of them jested that they seemed to be training the future leadership of the Orthodox Presbyterians and the Conservative Baptists.Then the hostess got a telephone call from her teen-aged son, who was attending a meeting of Young Life. The conversation turned to Young Life, and the fine young man who headed up the program in the local high school. The host couple had two children involved, and they were delighted with what was happening. Another couple, one of the seminary professors and his wife, reported that their two sons were also deeply involved in Young Life in another high school in the city. They, too, were pleased about it; the wife wondered with pardonable pride how many mothers had sent two sons off to summer football camp, both with their Bibles packed on top of their sleeping bags.One of the denominational executives began to talk about the absence of any kind of solid content at the parish youth fellowship his kids attended; it seemed to be largely recreational. Another deplored his inability to get his kids to participate in his congregation’s youth program at all, although he admitted it was so inconsequential and poorly attended that he couldn’t blame them. He recalled the significance of his own church youth group experience when he was growing up, the familiarity with the Bible that came out of his Sunday school attendance, and the spiritual intensity of his adolescent religious experience. He frankly—and sadly—saw nothing in the parish where he and his family were involved that could provide anything similar for his own children. And he wished his kids would join Young Life!Major Denominational Youth Programs: The SixtiesThese dinner party guests were leading establishmentarians. Nothing could more vividly portray the youth dilemma in the churches of the so-called mainline denominations than their conversation. Where have all the young folks gone? Mainly to Young Life, or Youth for Christ, or Campus Crusade, or Inter-Varsity Christian Fellowship, or the Sunday evening program of a nearby Southern Baptist church. Or else nowhere. Mainline Protestant parish youth programs, with some notable exceptions, are moribund. Mainline campus ministries play to empty halls. Mainline denominational youth ministry bureaucrats, by and large, are still hooked on the greening of America.This is our heritage from the sixties. Nowhere in American society did the youth countercultural values of that decade receive a more sympathetic hearing than in mainline churches. And for understandable reasons. The idealism, the activist involvement, the commitment to radical change—all these the mainline groups applauded. We marched alongside the counterculture in the civil-rights movement, and the anti-Vietnam War movement. We had a common cause. Draft card burnings nearly always featured a William Sloan Coffin or Dan Berrigan right up in front of the TV cameras. Youth was the “cutting edge.” Innumerable religious retreats plumbed the theological profundity of Beatles’ songs (especially “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” the tunes of which can still bring on an attack of acute nostalgia for anyone who, like me, was working with young adults during that period).Many of today’s mainline denominational executives cut their teeth on the counterculture. Radical protest was the norm of their formative years. Today they find a newer generation of young people to be baffling and unsettling, success oriented, nonprotesting, traditional in values.Another major influence on their own spiritual formation was the human relations movement, which also reached its peak in the sixties and early seventies. Its groupiness, its “touchy-feely” games, its self-discovery and self-affirmation, its simulation and trust-building exercises were the “methodologies” of the period. The fact that they were all methodology and no theology seemed irrelevant at the time. It was a compliment in human relations circles to be called “process oriented,” an insult to be known as “content oriented.”Major Denominational Youth Work TodayThe above picture may be overdrawn, but it is accurate enough to have affected significantly the current shape of youth work in these mainline denominations. The counterculture is dead, except as the context for denominational youth programs. Campus ministry, especially, has provided it with a last bastion. Mainline campus ministries are often isolated from parish life and accountable only to ecumenical bureaucracies far removed from and independent of either the university administration or the people in the pew. Yet they are still trying to fan the embers of radical protest. And local church youth groups are all too often still playing the trust games or engaging in “value clarification.” Church members, by and large, do not understand what is wrong with youth programs in their congregations, and they are not sure what should be done to fill the vacuum. But they know a vacuum exists, and they want something done about it. No concern is higher on their agenda, as they press church hierarchies for action.Whatever the answer for mainline churches may be, many young people have not waited for their parents, or the young associate ministers who run the programs in their parishes, or their denominational bureaucracies to find out. Vast numbers of them have found theft own answer outside the mainline churches, in the evangelical, nondenominational youth movements.Evangelical Youth MovementsMost of the major evangelical youth movements antedate the sixties, but their greatest impact on mainline young people has come since the sixties. Bible study is their stock in trade. They work through young, dedicated, full-time staff workers, who are often required to raise theft own salaries. And in contrast to moribund denominational youth programs, these movements are flourishing.At the high school level, the largest is Youth for Christ. It operates campus-oriented evangelistic teen clubs at well over a thousand American high schools. Young Life is also a high school (and sometimes junior high) movement, with something over a thousand clubs. In addition, it operates weekend and summer camps. It has recently added an urban Young Life operation for inner-city teen-agers, mostly black, with an emphasis on justice and jobs as well as on its usual spiritual concerns.Campus Crusade is by far the largest and most aggressive of the evangelical youth organizations. It is probably the most conspicuous Christian organization on college and university campuses, and it has branched out into a number of other specialized youth and young adult ministries. It has a high school branch, and an extensive ministry to young adults in the American armed forces all over the world.Inter-Varsity Christian Fellowship has chapters on over 800 American campuses. They are student-controlled, although IVCF does have staff personnel. Its style of evangelism is lower key and considerably less aggressive than that of Campus Crusade, and its lifestyle expectations are less legalistic. Inter-Varsity is well known for its Urbana (University of Illinois) missionary conventions. Urbana ’79 undertook to motivate at least a thousand young people a year to enter overseas missionary service for the next five years. The majority attending were from mainline churches, the largest single group being United Presbyterians with 1,104 delegates.Another predominantly youth-oriented organization is the Navigators, which originated as a movement among enlisted men in the navy during World War II. In recent years Navigators has expanded its ministry beyond the armed forces to other young adult communities, primarily college campuses. The Fellowship of Christian Athletes is an organization of athletes and coaches banded together to influence young people. It sponsors high school “Huddles” and college “Fellowships.” Coaches’ clinics, rallies, and banquets are all widely used in a ministry aimed at personal evangelism.Although these are the best known, they are by no means the only evangelical youth and young adult movements. Collectively, the independent evangelical youth organizations are by far the most significant and influential Christian youth movement in contemporary American society. Theft influence, however, is reinforced from other sources.Christian Academies And CollegesMy young teen-aged daughter reported recently that she “can’t stand” the superiority of one girl in her Sunday school class, whose one-upmanship consists of frequent reminders in class discussion, “Of course, I go to a Christian school.” The Christian academies found in most cities are almost without exception evangelical in orientation, and frequently they represent the fundamentalist wing of evangelicalism. At the end of the seventies, between 700 and 800 new private Christian elementary schools or high schools were being launched each year. More than five-and-a-half million students are currently enrolled in private elementary and secondary schools, two-thirds of them in Christian schools.What is widely perceived as a decline in the public school system with its emphasis on social goals, the “professionalization” of the educational establishment, the succession of educational fads (“progressive schools,” “whole-child” and “child-centered” emphases, “existential” education, “open classrooms”), the demise of discipline, and the widely documented decline in standard achievement and SAT (Scholastic Aptitude Test) scores, all have led many to seek alternatives. The traditional upper-class private schools are largely for the rich. The Christian academies, which frequently have higher academic standards than public schools, have provided the only real alternative for the not-so-rich, including many liberals from mainline groups.The evangelical colleges provide a continuation of the same educational influences at a higher level. They are unlike the Christian academies, to which many children are sent for reasons unrelated to evangelical orientation by parents seeking discipline and academic emphasis; the evangelical colleges are usually chosen explicitly for their religious stance. Parents distrusting the secular scientific world view, and the absence of constraint in the student environment of secular universities and the liberal mainline denominational colleges, have chosen evangelical colleges for their children. Young people of evangelical convictions have chosen them for themselves.Attitudes And TrendsReports from nondenominational evangelical youth organizations, Christian academies, and evangelical colleges are not the only source of data on what is happening to young people of mainline churches. The Princeton Religious Research Center, which bases its reports of religious trends on polls conducted by the Gallup organization, reports that the evangelical movement is strong among the nation’s youth. Evangelical gains, “often at the expense of mainline churches,” according to the center, are evidenced by the high percentage of teen-agers (44 percent of those identifying themselves as Protestants and 22 percent of the Catholics) who say they have had a “born again” experience.Similar evidence came from a Religious News Service tum-of-the-decade report on increasing interest in religion among college students in the second half of the seventies. The RNS survey saw the trend as conservative, pointing to such indications as the growing popularity of religion courses, with the addition of such courses and of departments of religion by responsive administrations, increasing attendance at religious assemblies, and growing willingness to voice religious opinions in class.The report noted the popularity of informal Bible reading or study groups in dormitories. Military chaplains have also observed a striking increase in such Bible study groups in barracks, camps, and ships. The Princeton Religious Research Center reported that 33 percent of Protestant teen-agers and 20 percent of the Catholics say they are involved in Bible study groups.The Princeton Center sees one of the characteristics of youth in the dawning eighties to be a return to traditional values. Except for marked differences on certain social issues (acceptance of the use of marijuana, and sexual freedom), the study found remarkably little difference between the attitudes of teen-agers and college students on one hand, and those of older Americans on the other. This shows a marked swing toward traditional values.These findings were further confirmed by a 1979–80 survey of students listed in Who’s Who Among American High School Students. It identified a decidedly conservative trend among high school leaders. Though religion has always played a significant role in the lives of this particular group, a striking 86 percent in this survey said they belonged to organized religion, up sharply from 70 percent in the 1969–70 poll 10 years earlier. Three-quarters said religion was an important part of their lives, and 67 percent claimed to have chosen their religious beliefs after independent personal investigation.What are young people looking for? All too often the liberal mainline establishment envisions them as seeking channels for idealism, for protest, for action aimed at bringing about social change. The youth counterculture of the sixties and early seventies, Christian and secular, was indeed seeking such channels. But it is questionable if even then a significant number of young people were seeking such channels to express a distinctively Christian idealism. Today’s social activists in the mainline church establishment are, by and large, responding to a Christian dynamic. Their meaning structure is a deep faith, acquired often in a more conservative church environment in their youth. But the generation they have produced in mainline churches, where attention is fixed on social change, lacks that rooting in a deep faith. Members of this generation are finding the meaning structure the seek in the evangelical youth movements, the evangelical colleges, and in a turn toward traditional values and conservative religion.All these reflect the theological stance of evangelical Christianity. Thomas C. Oden, a mainline seminary faculty member who refers to himself as a reformed liberal, speaks of “postmodern orthodoxy.” He says: “The sons and daughters of modernity are rediscovering the neglected beauty of classical Christian teaching.… They have had a bellyful of the hyped claims of modern therapies and political messianism to make things right. They are fascinated—and often passionately moved—by the primitive language of the apostolic tradition and the church fathers, undiluted by our contemporary efforts to soften it.… Finally my students got through to me. They do not want to hear a watered-down modern reinterpretation. They want nothing less than the substance of the faith of the apostles and martyrs.”Significance is generally ascribed to trends among young people in terms of what they foreshadow for the adults of tomorrow. A fairly clear picture seems to be emerging. Many of our youth have left us. They no longer see the church as a meaningful part of their lives. But a significant part of those still with us are young evangelicals. In 1979 the general assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the U.S. began for the first time to record the results of a straw vote of the Youth Advisory participants alongside the official action of the commissioners. On a surprisingly large number of issues with an identifiable “conservative” and “liberal” side, the youth vote has been more conservative than that of the adults. Some of these evangelical young people are being shaped in our own congregations, particularly those congregations that make up the evangelical wing of the mainline denominations. But many are finding their meaning structure elsewhere.Youth for Christ, Inter-Varsity, Christian academies, and nondenominational evangelical colleges are all now playing a part in shaping the new generation in the mainline churches.Nowhere is the future leadership of the church more clearly foreshadowed than in the seminaries. It was the seminaries of the fifties, sixties, and seventies that nourished today’s leaders on a diet that progressed from Barth to Bonhoeffer to Bishop Robinson and Harvey Cox to Gustavo Gutierrez. If denominational seminaries seemed too confining to earlier generations, the more adventurous went off to interdenominational Yale, Harvard, Union, Chicago, or perhaps to Berkeley. Now the more adventurous are forsaking denominational seminaries to go in the opposite direction. They are going to Fuller and Gordon-Conwell. The largest Presbyterian seminary in the world (in terms of the number of Presbyterian candidates for the ministry enrolled) is Princeton. But the second largest is Fuller. And third is Gordon-Conwell.Further, there is evidence that students in the mainline denominational seminaries are coming from conservative backgrounds. Those seminarians whose sense of calling has been nourished in their home churches are coming from the evangelically oriented mainline congregations.A 1979 study of candidates for the ministry within my own denomination, the Presbyterian Church in the U.S., showed that 44 percent of all candidates came from just 82 congregations—2 percent of the PCUS congregations, with 10 percent of the membership—and that most of these were known as conservative congregations. Student bodies are more and more evangelical. The seminary professor quoted earlier as saying his seminary was training the future leadership of the Orthodox Presbyterians and Conservative Baptists was dead wrong; it is training the evangelical future leadership of his own mainline denomination.There are some indications that mainline denominations may be getting the message, and that a genuine renewal of youth work may be developing. The early eighties have seen a spontaneous movement among many mainline groups in the direction of the recovery of a pattern of an earlier day with the reemergence of youth councils, youth rallies in local areas, and a growing call for denominational resources with Christian content, rather than just methodology. Whether a real recovery of mainline youth programs is on the horizon remains to be seen, but early signs are encouraging.Meanwhile, however, the wave of the future is already upon us. Where have all the young folks gone? They’re over at Young Life, studying their Bibles.Human trafficking (78%) and poverty (71%) have held steady among top concerns, occupying first and second place in the yearly list. Persecution now ranks third, though concern for climate change (62%) and the refugee crisis (61%) have also risen (from 57% and 55%, respectively).

Last year, Christian persecution ranked last.

However, a new question about COVID-19 displaced all but human trafficking, with 77 percent of Catholics “very concerned.”

The survey drew from 1,000 Catholics, with a margin of error of about 3 percent. In the sample, 58 percent were white, 34 percent were Hispanic, 4 percent were black, and 3 percent were Asian.

Across the board, they want more than prayer for the persecuted church.

“It is my hope that leaders around the world embrace the fundamental human right of religious freedom,” said Marlin, “and promote a society that respects ethnic, cultural, and especially religious diversity.”