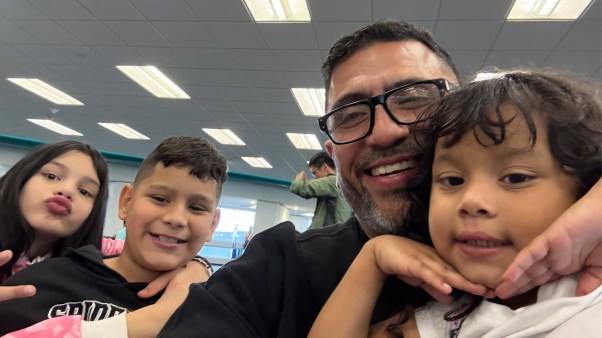

In every family’s lore, peripheral characters pop up here and there, sometimes for a span of a few years, sometimes for decades. As you survey your memory, you will see them there—not doing or saying much, not playing major roles in any dramas of the day, but simply in the background.

My family seems to attract a particular type of peripheral character: people who have few intimate attachments or are estranged from the ones they started with. They are a little quirky—sometimes you might go so far as to say “a little off.” In short, they are loners. They worked with my dad or ran into my aunt at morning Mass and were somehow claimed by us. From then on (perhaps against their own will, for all I know), they were drawn into the current of my family’s life. They tagged along. They appeared at birthdays and Fourth of July parties and Sunday afternoon visits, and they came over for Christmas Eve. Christmas Eve, in particular, is where I see these people, year after year, in my memory.

At least once, I complained to my parents. Strangers on Christmas Eve, unless they came bearing gifts, did nothing to endear themselves to my rapacious little heart. They put us on company manners. They forced us into the awkward, shuffling, small-talk routine peculiar to adults and children. They competed for my parents’ attention. They changed the dynamic.

Why couldn’t it just be us at Christmas? Why, tonight of all nights, could we not simply enjoy the giddy closeness and warmth, the endless inside joke that is a happy domestic party? I think the answer was something like, “We’ve been given so much, and other people so little. And it’s Christmas. People shouldn’t be alone at Christmas.”

If we’ve been given so much, I thought, then how come the pepperoni on the cheese tray always goes so fast? But adulthood is one long exercise in admitting your parents were right, and now I do.

Not that there wasn’t truth to my complaints, hardhearted as they might have been. You really do lose something precious and fragile when you invite in strangers. Many lonely people are lonely for a reason—unable or unwilling to give and take the way most do, embittered or driven by alienating compulsions.

And I would bet money that the gift we offered was a mixed blessing. I have been in this position many times, far from home at Christmas, relying on the graciousness of friends to include me in their family circles. At a certain point of heartsickness, the sting of always enjoying by grace what others enjoy by right competes with gratitude. You long for the people for whom you are first. It would be a very hard thing to have no such people.

There is a wound embedded in the structure of hospitality—the fact that to be welcomed in, someone has to be on the outside first. Someone always has to play the part of Odysseus, bereft and supplicant, even if only in the most vestigial and symbolic sense, as when neighbors reciprocate visits.

Still, it’s better not to be alone on Christmas. I have never turned down an invitation to turkey dinner. And I am grateful that none of the people we invited over the years ever turned us down, even if sometimes it came at a cost I will never fully understand. If nothing else, I am glad that, early in life, they muddied up my nice Christmas Eve.

What constitutes a nice Christmas Eve anyway? If you are of Italian extraction, like many of my friends and relations, the answer is not just pepperoni but probably several different species of fish: calamari fried in crunchy, lemon-scented rings; sardines layered with red peppers on an antipastos board slick with olive oil; bread dipped in whipped salt cod. For myself, a nice Christmas Eve is the vigil Mass, then decorating the tree by firelight; reading a story to the younger generation, who in this ideal scene have been flown in along with their parents; then champagne, fancy little bites of puff pastry and artisan ham, and the rug rolled back for dancing.

In purely material terms, we all have our nice Christmases, usually in the form of to-do lists. We need to go get firewood from that guy in the pines who sells it crazy cheap; we need to pick up a case of bubbly; we need to make sure the children’s stockings haven’t molded during their time in the basement; we need to make dough and peel potatoes and acquire, slice, brine, and stuff various meats. And as stressful as these preparations sometimes are, they’re not bad. It is an irony of the human condition that 15 hours of work often go into any three hours of revelry—and an even stranger irony that this bad exchange is usually, somehow, so very satisfying.

But something stalks the footsteps of the material, champagne-and-calamari, to-do-list version of Christmas. It is a doppelgänger, more seductive and somehow even more demanding. It is the Perfect Christmas.

The Perfect Christmas turns the mundane to-do list into scaffolding for the emotional consummation of a hundred cross-hatched desires. If we work hard enough, happiness will come easily. If we take the perfect Christmas card photo, if we set the perfect festive tablescape and cook the perfect prime rib (if anyone knows an idiot-proof method for this, please get in touch), if we purchase and receive the perfect gifts, we will be happy and know ourselves to be happy and be seen to be happy and know that we are seen to be happy—with all these layers of refraction never compromising the snowflake purity and refulgence of that immediate, satiating happiness.

So often, the happiness we desire is domestic in nature, that closed circle of giddy warmth. Christmas is the time of year when families come together, which means that Christmas is our chance to make up for all those days of the year spent in separate rooms, all that time spent ignoring each other on our phones. Christmas, one perfect day, is our chance to erase the quarrels and sloth and apathy, the squalid minutiae. On our Perfect Christmas, we will get to experience what being a family is all about.

Until, of course, people ruin it, as they always do, with their squabbles, failures, needs, competing points of view, and a hundred other potential points of departure from the vision board. The Perfect Christmas—an ideal that can be constructed and pursued without its maker ever becoming aware of it—usually suffers death by a thousand cuts from the sharp edge of reality.

Just as with hospitality, there is a corresponding wound, an ache embedded in family life that emerges when we are most immersed in its delights. It is the gap, however miniscule, between what we hope for, what should be, what we may feel hidden beneath the fleshly moment-to-moment reality—and what we actually experience. To fight the gap by chasing after the Perfect Christmas is a short road to tears.

Hospitality is mysterious: a transcendent correction to the problem of exclusion that retains and even emphasizes the pain that it turns into joy. Family life is mysterious: a burning core of the solidarity and communion for which humans were made that always reveals a shortfall in the moment of its happiest achievement. Hospitality and family are among the sweetest things we experience in this life precisely because the desires involved will never be perfectly satisfied in this world. The joy and the pain both point us to something beyond them.

So, bring out the prime rib and puff pastry or slice-and-bake cookies. Do things differently for a day. Extend the invitation. Make the invitees feel special, and ask nothing in return. People shouldn’t be alone at Christmas. The imperfect Christmas will mean unfinished to-do lists, hurt feelings, disappointments, awkward silences, boring conversations, the pepperoni on the cheese board disappearing too fast. It will mean songs and colored lights and homecomings and Waterford crystal, and it will make you so very happy but never happy enough. Celebrate it anyway. The celebration will never make us happy enough, but the reason we celebrate will.

Christmas proclaims, among other things, our place around the divine hearth, the intimate circle where we enjoy all the unquestioned rights of heirs, all by the humbling generosity of grace (Rom. 8:17). We are beloved children of the house, but we were once beggarly strangers asking for space in the stable (Luke 2:7). In this life, at any given moment, we are asked to play one or the other. May we never forget that we are either. May we always rejoice that we have been both.

Clare Coffey is a writer whose work can be found in Plough, The New Atlantis, and elsewhere.