Halfway through the Great War, on November 30, 1916, a small group of European leaders managed to attend the funeral of Franz Joseph, ruler over the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In a ceremony scripted by the emperor before his death, the grand cortege carrying his coffin halted outside the Capuchin monastery in Vienna, where all the Hapsburg emperors were laid to rest.

The herald, speaking on behalf of the dead emperor, knocked on the monastery door.

“Who is knocking?” shouted the abbot inside.

“I am Franz Joseph, emperor of Austria, king of Hungary.”

“I don’t know you.”

Again the herald shouted: “I am Franz Joseph, emperor of Austria, king of Hungary, Bohemia, Galicia, Dalmatia, Grand Duke of Transylvania, Duke of—”

“We still don’t know who you are,” interrupted the abbot.

At this moment, the herald fell on his knees and in front of all assembled declared, “I am Franz Joseph, a poor sinner, humbly begging God’s mercy.”

“Enter then,” the abbot said. And the gates opened.

The funeral symbolized an outlook already in an advanced stage of decay by the early 20th century. Settled beliefs about the religious dimension of human life were becoming unsettled. Assumptions about good, evil, and morality seemed to have vanished into the killing fields of the 1914–18 war. By the end of the conflict, the emotional and spiritual lives of millions of ordinary Europeans were caught up in a no man’s land of doubt and disillusionment.

Two of the most influential writers of the 20th century, J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis, were soldiers in the Great War. They fought in the trenches in France, in what one contemporary called “the long grave already dug.” They emerged from the mechanized slaughter of that conflict physically intact, but just barely.

No man could pass through the fires of the Somme and Arras and remain unchanged. For Tolkien, his war experience left an enduring sadness. Yet he also found that his imaginative cast of mind, his early taste for fantasy, was “quickened to full life by war.” For Lewis, the conflict deepened his youthful atheism—the growing conviction that if God existed, he was a sadist. Paradoxically, the war years also launched Lewis on a spiritual quest, a desire for “Joy” which ultimately led him on a remarkable journey of faith.

The lives of these two men intersected as they were launching their academic careers at Oxford University. They soon formed a bond that, given the reach and influence of their novels, must rank as one of the most consequential friendships of modern times.

There was nothing inevitable about it. Tolkien was a devout Catholic, Lewis an Ulster Protestant and lapsed Anglican. At their first English faculty meeting, they circled each other like tigers in the wild. Yet they soon discovered that they loved many of the same things: ancient myths, epic poetry, and medieval stories of honor, chivalry, and sacrifice.

The horror of the First World War had instigated a cultural backlash, setting loose forces that tore at the moral and spiritual foundations of Western civilization. Both men were determined to fight back. They formed the nucleus of a group of like-minded writers, all resolved to establish a beachhead of resistance amid the raging storm of ideas.

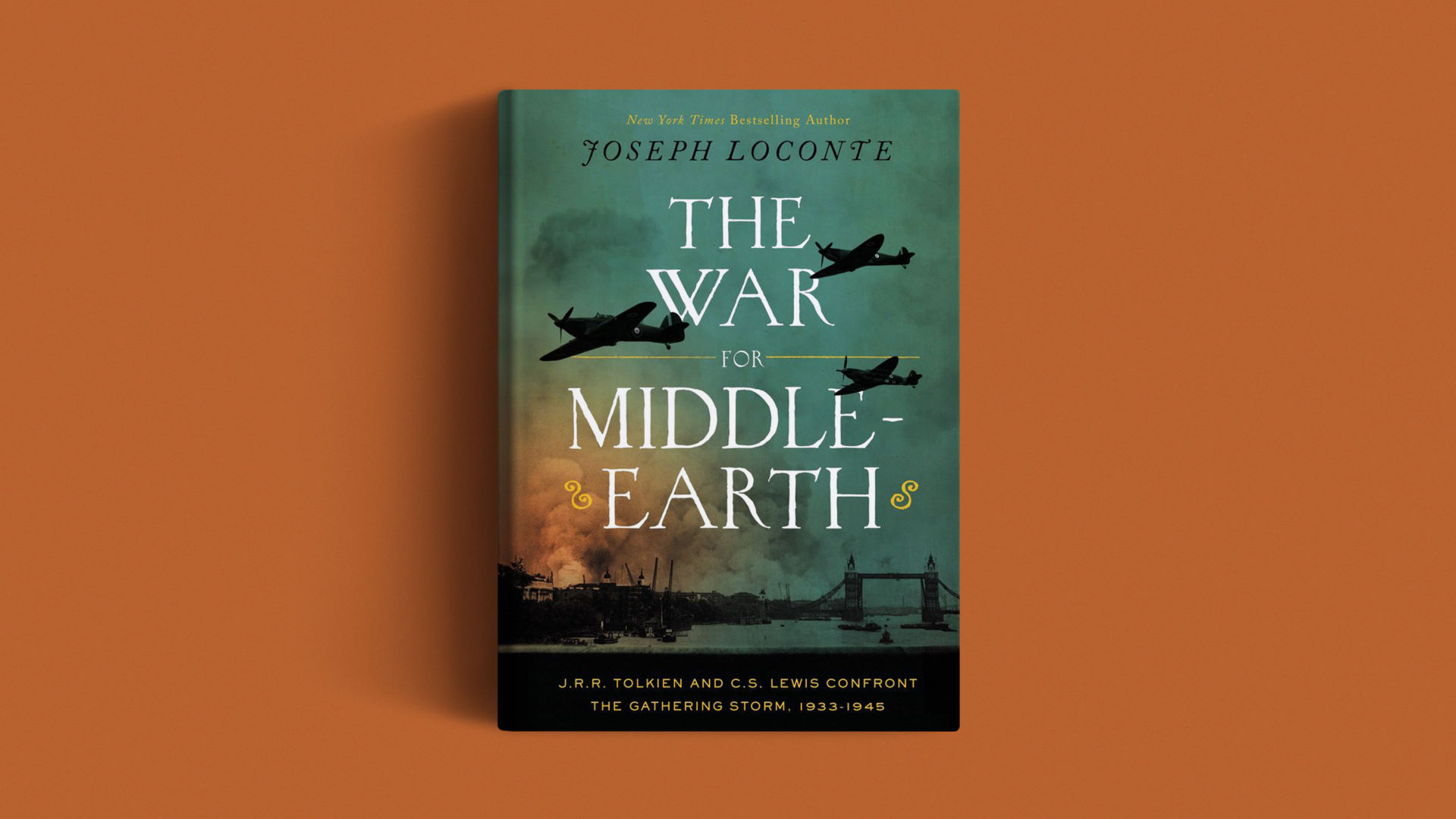

But barely 20 years after surviving what was the most devastating conflict in history, Tolkien and Lewis would watch in anguish as new forces of aggression gathered and dominated Europe’s geopolitical landscape. The onset of the Second World War utterly transformed not only their lives but also their literary imaginations. Their most beloved works—including The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, The Screwtape Letters, Mere Christianity, and The Chronicles of Narnia—were conceived in the shadow of this conflict.

“Talent alone cannot make a writer,” observed Ralph Waldo Emerson. “There must be a man behind the book.” Behind the extraordinary works of Tolkien and Lewis stood a cloud of witnesses: individuals whose contributions to the literary canon of Western civilization provided inspiration for their epic novels. Both authors instinctively looked to this inheritance and were nourished by it in wartime.

As a result, they acquired something that our modern era has mostly abandoned: perspective. Rooted in the great books of the Western tradition, they knew where to look for wisdom, virtue, courage, and faith. Intimate knowledge of the past braced them for the crisis years of 1933 to 1945. In this, they reinforced each other’s best instincts. “My entire philosophy of history,” Lewis once told Tolkien, “hangs upon a single sentence of your own.”

Could an entire philosophy of history be summed up in a single sentence? Which one? Lewis is citing a passage from The Lord of the Rings, in which Gandalf explains to Frodo Baggins something of the ancient struggle for Middle-earth. “There was sorrow then, too,” the wizard says, “and gathering dark, but great valor, and great deeds that were not wholly vain.”

The lives of Tolkien and Lewis were already embedded in this story when another disastrous war unleashed upon the earth a storm of human misery. “Middle-earth, I suspect, looks so engagingly familiar to us, and speaks to us so eloquently,” writes biographer John Garth, “because it was born with the modern world and marked by the same terrible birth pangs.” We cannot fully appreciate the achievements of these two remarkable authors until we understand their historical context and the deep awareness it gave them of life’s sorrows.

Yet suffering is only part of their story, held in check by something stronger: gratitude. The Roman statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero called this quality “not only the greatest of virtues, but the parent of all the others.” Like no other authors of their age, Tolkien and Lewis used their imagination to reclaim—for their generation and ours—those deeds of valor and love that have always kept a lamp burning even in the deepest darkness.

Joseph Loconte is an author, historian, and filmmaker. He serves as Director of The Rivendell Center in New York City.