When frontier evangelist “Raccoon” John Smith shared his testimony for the first time, he was nervous.

In the early 1800s, he recounted his experience in typical fashion: He had been lost but now was found. Then he waited as the church held a vote.

The congregation deliberated over the plausibility of his testimony until someone called the question: All in favor, raise your hand.

Christians have always felt compelled to testify. And at least since Acts 9:8, when Paul showed up blind in Damascus, other Christians have struggled to figure out how to evaluate those testimonies.

A democratic vote is an unusual solution, but the problem comes up again and again. How do you decide to accept someone’s story of salvation? How do you assess the veracity of spiritual rebirth?

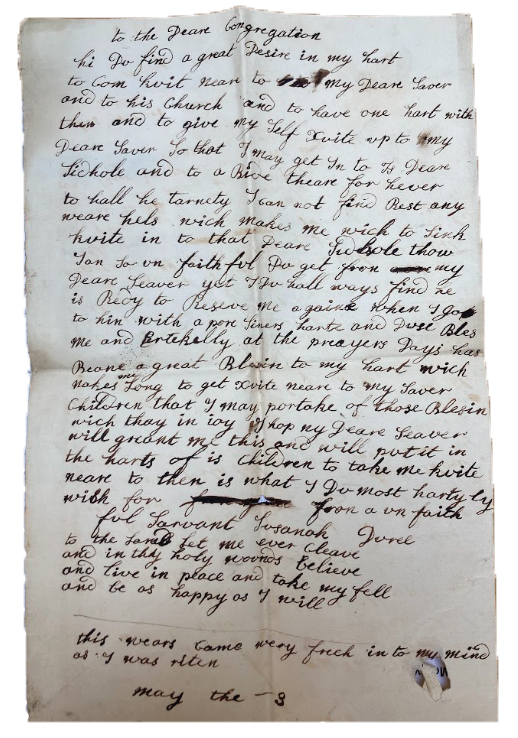

Archival records in the United States and the United Kingdom are full of testimonies submitted for evaluation. Historian Tucker Adkins told CT he found a 1740s letter from a London woman addressed “to the deare congregation.” The letter says, “Hi do find a great desire in my hart to com kuit near to my deare Saver … and to a bide theare fore hever to hall he tarnety” (“I do find a great desire in my heart to come quite near to my dear Savior … and to abide there forever to all eternity”).

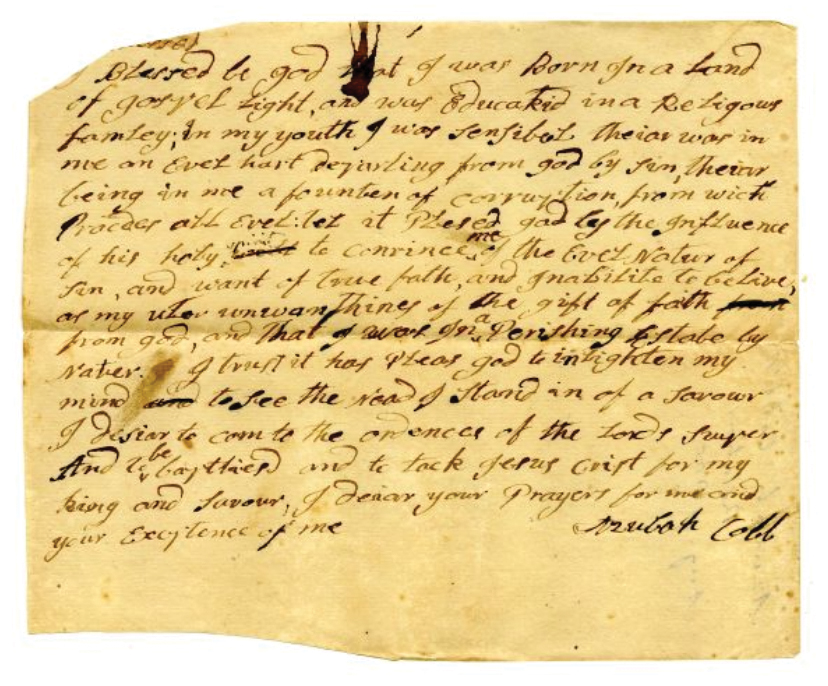

Meanwhile, in Massachusetts, a woman named Azubah Cobb submitted her testimony on a scrap of now-yellowed paper. “It plesed God by the influence of his Holy Spirit,” she wrote, “to convince me of the evel natur of sin, and want of true fath.” (“to convince me of the evil nature of sin and want of true faith”).

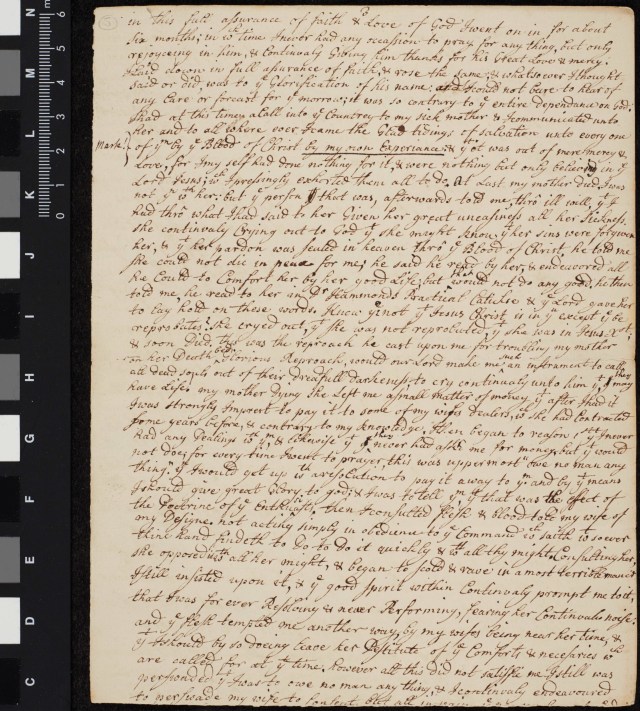

Occasionally, Adkins has also discovered traces of the evaluation of these testimonies. A man named Joseph Cooper, for example, wrote a seven-and-a-half-page letter to Methodist leader Charles Wesley, explaining how he came to the “glad tidings of salvation … by my own experience.” In the margin next to “own experience,” someone—Wesley?—wrote, “Mark!” At the end, there is an appended note that Methodists would accept the testimony.

“Raccoon” John Smith, for his part, came to think Christians put too much weight on the evaluation of conversion experiences. He thought if someone said, “Jesus is Lord,” that should be enough. We don’t need to hold a vote.

But Christians, of course, still feel compelled to say what God has done for them. And other Christians have to decide what they think about it.