Born into slavery in 1862, Black journalist Ida B. Wells educated herself and, during the late 1880s, wrote for Christian publications “in a plain, common-sense way on the things which concerned our people.” She added, “Knowing that their education was limited, I never used a word of two syllables where one would serve the purpose.”

Wells described in 1886 her sense of God’s sovereignty: “God is over all and He will, so long as I am in the right, fight my battles.” Her diary in 1887 noted,

Today I write these lines with a heart overflowing with thankfulness to My Heavenly Father for His wonderful love and kindness; for his bountiful goodness to me, in that He has not caused me to want, and that I have always been provided with the means to make an honest livelihood.

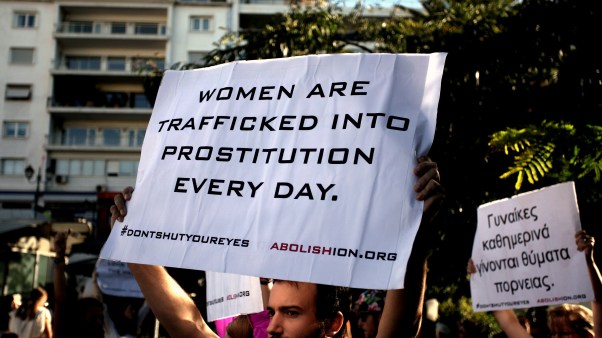

Wells made her biggest impact in local journalism as part-owner and editor of the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight in 1892 after a mob lynched three Black men. One of them was Thomas Moss, a postal worker, Sunday school teacher, and friend of Wells. She was godmother to one of his children.

Wells told the real story: A white store owner had maliciously accused Moss and his friends of crimes because their shop, People’s Grocery, had drawn customers away from the white-owned store. Wells recommended in her newspaper that Black people “leave a town which will neither protect our lives and property, nor give us a fair trial in the courts, but takes us out and murders us.”

Two pastors migrated from the city with their entire congregations. White housekeepers had a hard time hiring maids because many fled to Chicago. Other Black people boycotted the streetcars and walked instead. Officers of the City Railway Company came to the Memphis Free Speech office and pressured Wells to use the paper’s “influence with the colored people to get them to ride on the streetcars again.” Instead, she penned a bold editorial and, foreseeing the reaction, headed to New York.

The editorial began, “Eight negroes lynched since last issue … five on the same old racket—the new alarm about raping white women.” Her most potent paragraph:

Nobody in this section of the country believes the old thread-bare lie that Negro men rape white women. If Southern white men are not careful, they will overreach themselves and public sentiment will have a reaction; a conclusion will then be reached which will be very damaging to the moral reputation of their women.

The suggestion that some white women lacked virtue brought a sharp reaction from other Memphis newspapers. A Daily Commercial writer huffed, “That a black scoundrel is allowed to live and utter such loathsome and repulsive calumnies is a volume of evidence as to the wonderful patience of Southern whites. But we have had enough of it.” An Evening Scimitar writer proposed “to tie the wretch who utters these calumnies to a stake at the intersection of Main and Madison.”

A mob broke into the Memphis Free Speech office, damaging Wells’s press and vandalizing the building. Wells could not safely return to Memphis. Shestudied accounts from white newspapers along with statistics from the Chicago Tribune, and she wrote an article in The New York Age that documented 878 lynchings from 1883 through the first half of 1892. She criticized lynch mobs but didn’t stop there: “The men and women in the South who disapprove of lynching and remain silent on the perpetration of such outrages, are … accessories before and after the fact.”

Citing the movement of Black people out of Memphis after the three lynchings, Wells urged Black people to use their economic power to force change. The white Memphis residents who had hoped to shut up Wells instead saw her lynching exposé reach tens of thousands more people than it would have had she stayed in Memphis. The New York Age printed extra copies to send throughout the South, including 1,000 to Memphis. Donors paid to publish the exposé as a pamphlet: “Southern Horrors: Lynch Laws in All Its Phases.”

Wells received a boost from a famous former slave, 75-year-old Frederick Douglass:

Brave woman! you have done your people and mine a service which can neither be weighed nor measured. … If American moral sensibility were not hardened by persistent infliction of outrage and crime against colored people, a scream of horror, shame and indignation would rise to Heaven wherever your pamphlet shall be read.

Wells hit the lecture circuit in the Northeast and in England.

Her street-level reports of lynchings reached a wide audience and brought unflattering attention to the practice and to the South, where few spoke out against the evil. It turned out that 1892, the year of Southern Horrors, was the peak year for US lynchings: 231, according to statistics from the Tuskegee Institute. The horror continued but gradually declined. Sadly, while some states passed anti-lynching laws, lynchers were almost never penalized. Congress remained inactive until early in the 20th century, when the House of Representatives passed anti-lynching legislation—which Senate filibusters killed.

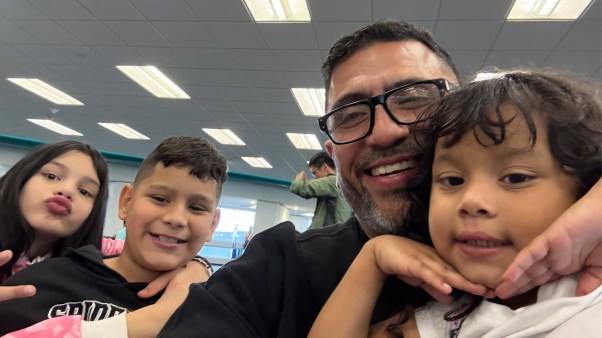

In 1894, Wells moved to Chicago, and the following year she married lawyer and journalist Ferdinand Lee Barnett, a widower with two children from a previous marriage. She added four more children during the next decade and made motherhood her primary occupation. She also established Chicago’s first kindergarten prioritizing Black children, located in an African Methodist Episcopal church, and volunteered with civil rights and women’s suffragist groups.

She continued some journalistic work and in 1917 wrote investigative reports for The Chicago Defenderon the East St. Louis Race Riot.

Wells died in 1931 with little recognition from other journalists, but the National Association of Black Journalists and other groups have now established awards in her name. In 2020 she received a Pulitzer Prize special citation “for her outstanding and courageous reporting.” In 2022, Congress passed a federal anti-lynching law as a symbolic way of belatedly recognizing the nearly 6,500 lynchings that took place in the US from 1865 into the first half of the 20th century.

This short account draws from a chapter on Ida B. Wells in Marvin Olasky’s Moral Vision (Simon & Schuster, 2024).