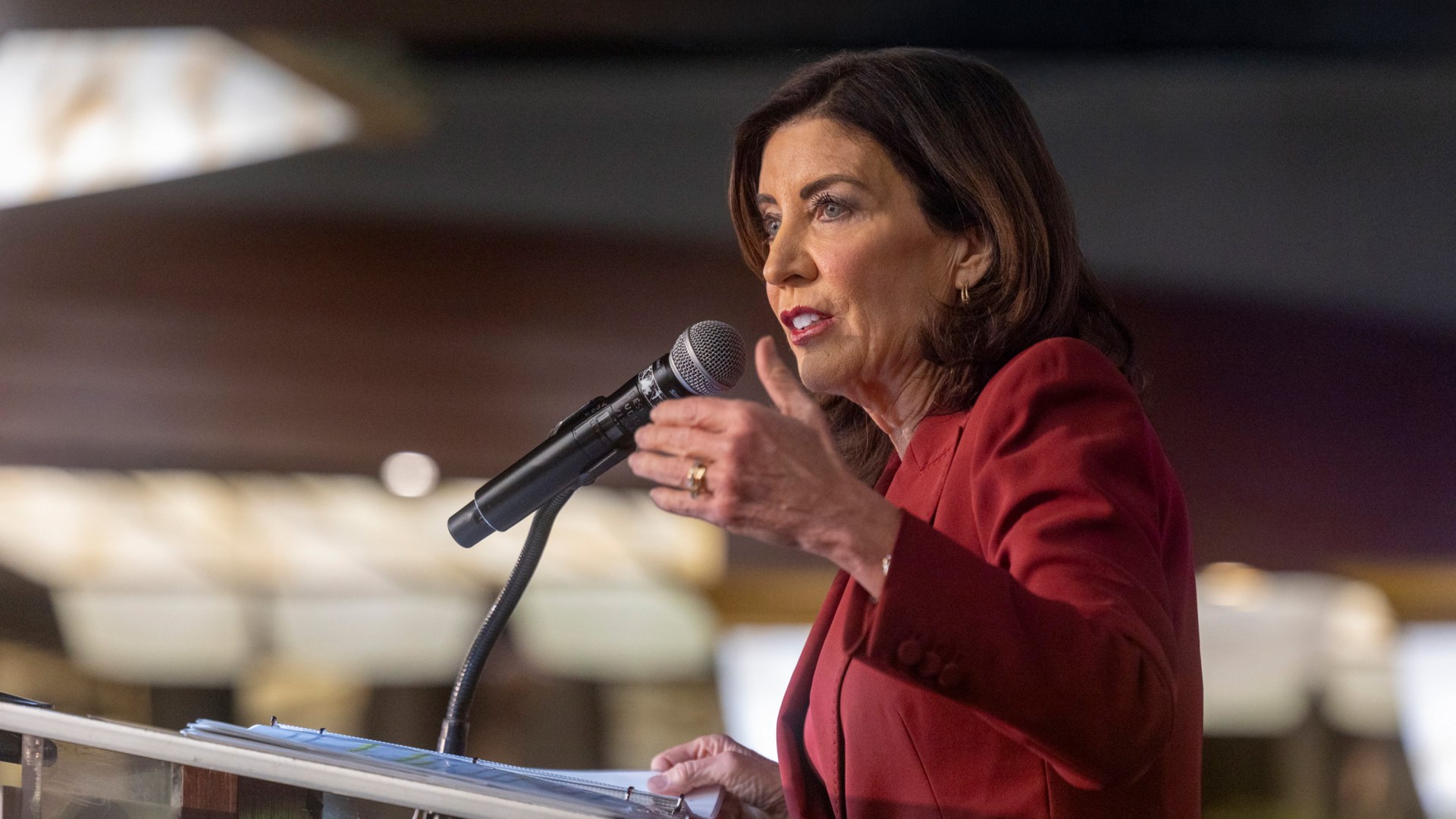

On February 6, New York Governor Kathy Hochul signed a bill legalizing medically assisted death, joining Illinois and 12 other US jurisdictions in allowing patients to take lethal medication under certain conditions.

“Our state will always stand firm in safeguarding New Yorkers’ freedoms and right to bodily autonomy, which includes the right for the terminally ill to peacefully and comfortably end their lives with dignity and compassion,” Hochul said. Although the US first faced this debate when Oregon legalized assisted suicide in the 1990s, such laws are becoming more common.

CT reached out to Dr. Lydia Dugdale, professor of medicine and director of the Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at Columbia University and author of Dying in the Twenty-First Century and The Lost Art of Dying. A New York resident and practicing internal medicine physician, Dugdale has followed the New York debates closely.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

My first question is just background on what happened for those who don’t know: What is this law allowing, and how will that impact the medical field? What’s assisted suicide versus euthanasia? And does this differ from what’s happening in Canada?

When it comes to MAID, which is the acronym people use for medical assistance in dying or medical aid in dying, there are two main routes. In the United States, the only route permitted in any jurisdiction where it is legal is lethal ingestion. That involves taking a cocktail of pills, crushing them, forming them into an elixir, and then self-ingesting.

The other route is lethal injection, which requires a health care practitioner to place an IV in the person who wishes to die and then administer a lethal dose of a medication that will ensure death. This is legal in Canada, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Colombia, and several other jurisdictions around the world. But it is not legal in the United States outside of the lethal injection that is used on death row for capital punishment.

New York State has been considering this legislation for about a decade. It’s come before the state government almost every year. When Governor Hochul agreed to sign the legislation in December, she said that it had to have certain amendments to enhance its safety. Those amendments were presented to the governor, who signed them last Friday, which means that in six months, the state of New York will become the next jurisdiction to perform so-called physician-assisted suicide.

The amendments that make it distinct from many of the other laws include a mandatory waiting period of five days between when the prescription is written and when it can be filled. Some jurisdictions have eliminated a waiting period altogether. Other jurisdictions, there’s a 15-day waiting period. Waiting periods were initially seen as a source of safety, and now they’re seen more as an impediment to easy access to these lethal drugs.

Hochul also added something unique out of all of the states where it is legal: An oral request must be made by the patient for MAID, recorded by video or audio.

She’s also requiring mental health evaluations by a psychologist or a psychiatrist of patients who are seeking MAID. I think many will see that as an impediment to access too, because nationwide, there’s a shortage of mental health professionals. But that’s a reasonable requirement, because we know that people who seek to end their lives often do suffer from depression. And if they aren’t being assessed, then we could be hastening death for people who have otherwise treatable depression and don’t really want to die.

The other thing that’s notable for the New York law is that MAID there is limited to New York residents. Vermont and Oregon have opened the doors so anyone who can get to those states could qualify for medical aid in dying.

Can you explain why assisted dying is seen as wrong from a Christian standpoint? The argument for MAID is often the compassion argument: We do as much for animals who are in pain and help them end their lives.

There are many good reasons to oppose assisted suicide.

Arguments in favor of it include the compassion argument, the take-control-of-your body argument—which I think is very, very strong—and an argument for the professionalization of the dying process. So much of our living and dying and giving birth is medicalized and professionalized, and this is just yet another example of that. I think many people don’t understand self-killing as suicide. They think of it as just the medicalization of death, of the actual moment of dying.

But this is killing or aiding a suicide. Every major world religion has a prohibition on the taking of human life, and this certainly falls under that.

But even if we were to get outside of religious arguments, we should have concerns about how marginalized and impoverished patients might feel pressured to end their lives. They recognize that they’re a burden on their family. They don’t want to be a burden. Why not just end it all? Actually, that’s a common question that patients raise even in jurisdictions where physician-assisted suicide is not legal.

Similarly, there are folks with disabilities who feel like they’re constantly having to fight to have the medical system realize that their life is worth living. They also may feel pressured.

There’s also this concomitant problem of an aging population, a lack of caregivers to care for that population, and the enormous costs for caring for the elderly, especially those with dementia, in the last year of their lives. There will be tremendous pressure to try to figure out how to handle these costs, and in jurisdictions where physician-assisted suicide is legal, we already know that people will choose to hasten their deaths rather than to live out their lives because of the costs involved.

So I think we will see, from a governmental perspective, a keen desire to make MAID more widely available and to reduce impediments to access to it to handle this so-called problem of an aging population.

There’s also a well-documented phenomenon of suicide contagion. This has been discussed going back to the 1700s, when it was called the Werther effect. We have seen that when there is a high-profile suicide, other people in a similar demographic will also pursue suicide. And people studying what happens in regions where MAID or physician-assisted suicide is legal find that conventional suicide rises alongside assisted suicide.

When the process of taking one’s life or hastening death prematurely becomes normalized, the culture shifts. People begin to believe it is acceptable to end your life. I’m not saying one causes the other, but there certainly is that correlation.

Another argument I’ve heard is that we should make palliative care more available. Is that something you see as a viable alternative to address these related issues with aging?

That’s a really tricky question. Palliative care is also a version of medicalizing the dying process. Now, insofar as it is available and used prudently, it is a wonderful gift to dying patients and their families because the focus is on holistic care, relief of uncomfortable symptoms, relief of pain. It’s bringing the family together, addressing spiritual needs, et cetera. That’s a wonderful gift. Palliative care is not available everywhere, even in the United States. It’s certainly not available worldwide, but it’s not available in much of rural America.

Historically, palliative care clinicians have been opposed to the legalization of physician-assisted suicide or MAID because they have taken a professional view that it is not their role to hasten death. They’re there just to accompany patients to a natural end. Unfortunately, in jurisdictions where MAID is legal, it is often through the palliative care doctors or in palliative settings, in hospice settings, where MAID is enacted.

And then you get into this difficult situation where patients who might otherwise want to have access to palliative services that focus on symptom reduction refuse those services because they’re afraid that these very same doctors will hasten their deaths. That’s a real problem. So kind of a complex answer to a complex issue.

In terms of the political situation, is this the end of the road in New York? Could this law be overturned, or should we expect a domino effect for other states?

Illinois also legalized about the same time, and they start in September, so I guess New York will beat them to it. But I don’t know that it’s a domino effect.

The reason why I say that is, if you look at a graph from the Lozier Institute of jurisdictions that have legalized physician-assisted suicide, at least 26 states responded to the legalization in 1994—when Oregon legalized its Death with Dignity Act—by passing legislation that made it more difficult to take one’s own life through a medically assisted death. So maybe there’s not quite a domino effect—at least not in more conservative-leaning states.

But many states have passed bad legislation over the years, and here I think specifically about sterilization laws in the early 1900s. Those same states have chosen to overturn what they now consider to be bad decisions. So should New Yorkers move to a position where they recognize the harm that is coming from hastening so many deaths? Yes, it’s always possible to reverse the legislation. I think we always hold out hope.

Last, are you already hearing from doctors or Christians in general about how to respond?

I’ve heard from lots of people just in the last few days, anticipating this as it’s moved through the country and in Canada. Ewan Gallagher, my colleague in Canada, has published with CT, and he has a book now that he wrote for the church, How Should We Then Die. And the Canadian context, of course, is more difficult, but I would commend that book to anyone who identifies as a Christian and is trying to make sense of this.

But look, the reality is that mortality is 100 percent, right? All of us will die, and most of us live out our final days engaging the health care system in some way. That means we all will likely have to reckon with the question of legalizing assisted suicide, whether for ourselves or for our loved ones, if we live in jurisdictions where it is legal.

So I think the church needs to read Ewan’s book and do some serious thinking and teaching about this issue. And not just this question of hastening death but, more broadly, how to live and die well. My own work focuses on this, which is really critical for all of us.

For physicians, there’s a lot of trying to make sense of it in real time: How will this be implemented? What conscience protections will there be? Even some people who might not be opposed, necessarily, because of their view on bodily autonomy will still be concerned about what it means to be involved in hastening death. So yeah, there’s a lot of concern right now.

And just since Friday, health care leadership like hospital administrators are trying to think through what this will look like once they’re required by law to provide access come August. Originally, Hochul had said groups that were opposed could opt out, but now the law only says religiously oriented home hospice providers can opt out. So that’s concerning.