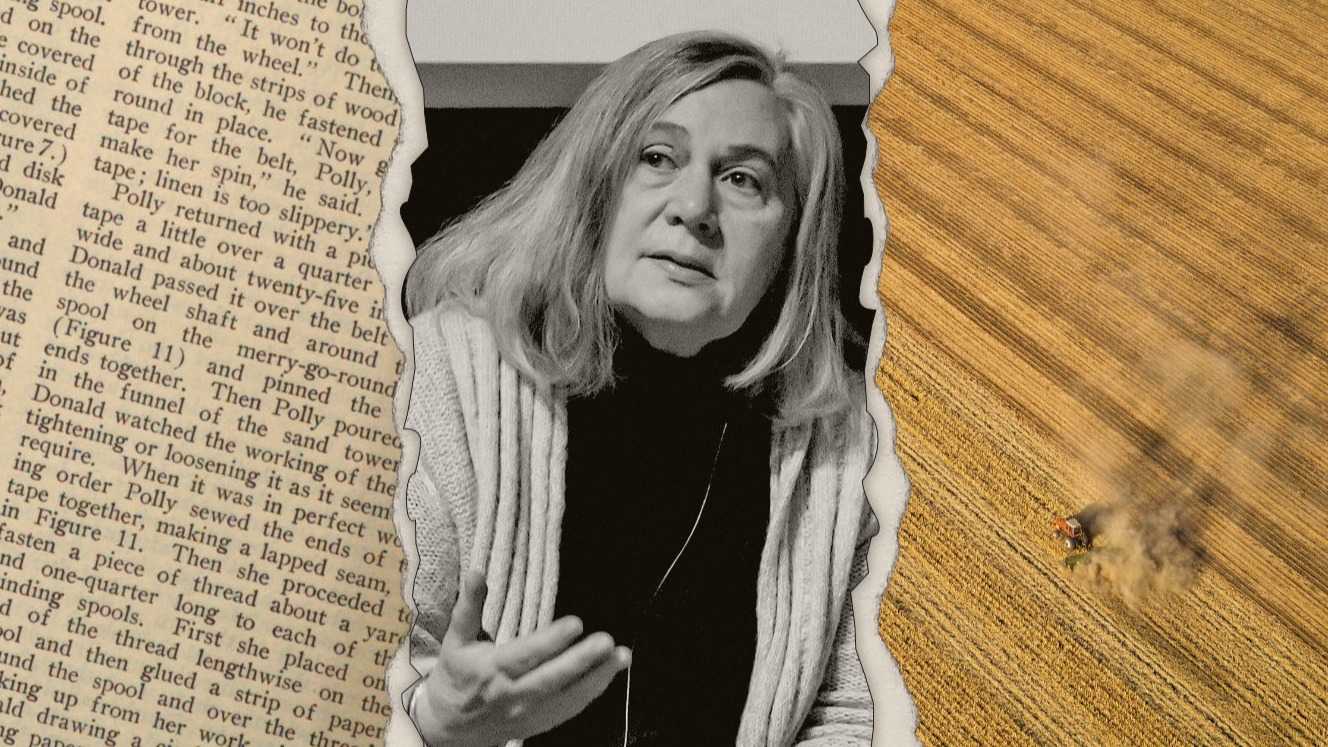

Cynthia Gibbs grew up five miles from Taveau Church, a small wooden building weathered by decades of declining membership and a deteriorating physical structure.

Outside Charleston, South Carolina, the church sits on land once owned by Henry Laurens, one of America’s founding fathers, a wealthy planter and slave owner.

At nearly 200 years old, the structure had become a shell of its former self with its story largely untold.

“Church has always played a critical role in our history,” said Gibbs, chair of the Taveau Legacy Committee. “When these sacred structures deteriorate and disappear from the landscape, so does all that history and its importance as to who we are as a people and all the contributions we have ever made.”

Black congregations of enslaved people and former slaves worshiped in Taveau decades before the Civil War, and subsequently the church also served as a Reconstruction-era schoolhouse, according to Gibbs.

The church served as a house of worship for over 175 years, first for Black Presbyterians and then for Black Methodists in South Carolina. Once the church fell to about a dozen members in the 1970s, it merged with a nearby United Methodist Church and stopped using its old building.

Even active congregations struggle to raise funds or secure financing for major building projects. For dwindling historic churches whose buildings have fallen into disrepair, it can be impossible.

Project costs add up quickly, and it’s hard to estimate how extensive or pricy a restoration could get. Older structures can require more specialized labor and supplies. Crumbling foundations and rotting wood need replacing, as do outdated plumbing and electric lines. Plus, historic buildings can be subject to regulations for preservation.

Many historic churches rely on grant funding to help cover needed repairs. Taveau began restoration two years ago. Gibbs is hopeful that future South Carolinians will be able to visit the building and learn about its history, thanks in part to funding from the Preserving Black Churches initiative of the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund.

The grant program provides $50,000 to $500,000 to churches with an active congregation or those being considered for new uses in the community. The initiative has awarded $275,000 to help in Taveau’s revitalization and efforts to make it a destination site.

In 2025, 30 historic Black churches were awarded a total of $8.5 million in funding to support preservation work, including structural restoration and management of the funds.

Overall, $21.67 million has been awarded through 113 grants since 2023, many going to buildings in Alabama, Georgia, and Ohio.

The grants also cover technical and marketing assistance. Grant recipients are launching programs, fueling community revitalization, and educating the public on the sites’ history.

“For generations, Black churches have anchored communities and fueled movements,” said Brent Leggs, executive director of the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund and senior vice president of the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

“Yet too many are at risk due to decades of disinvestment,” he added. “These places are not just buildings—they are living monuments to American resilience, leadership, and cultural brilliance. Equitable preservation ensures these sacred spaces are protected, celebrated, and passed on with pride.”

The African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund was launched in 2017 by the Washington, DC–based National Trust for Historic Preservation. Preserving Black Churches had its first cohort in 2023. So far, grant recipients include:

· The African Meeting House in Boston, where William Lloyd Garrison founded the New England Anti-Slavery Society in 1832.

· St. James African Methodist Episcopal Church in Columbus, Georgia, the second-oldest AME church in the state. The building was completed in 1876. Over the years, water damage has affected its twin turrets and steeple and its wooden doors, believed to have been carved by former enslaved craftsmen.

At Taveau, Gibbs and others hope to rehabilitate and restore the structure, which sits on 3.7 acres and includes a cemetery, and turn it into a destination site.

The building, a surviving example of rural antebellum architecture, was built in 1935 and became a center for Black Methodists in 1847 and a hub of Gullah Geechee life (a culture that developed among African descendants on the coastal Carolinas and beyond). The funding will go toward exterior restoration to keep the church structure standing.

Historic Black churches are most common in the South and in older cities, places with high concentrations of Black residents, according to Nichole R. Phillips, director of the Black church studies program at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology.

“In some respects, the importance of preserving Black churches is because the Black church is really under threat,” with more Black Protestants attending multiethnic churches, she said.

Congregations age. Younger families leave, sometimes citing the lack of women in leadership, lack of LGBTQ affirmation, or moral standards they view as outdated. And, increasingly, younger generations didn’t grow up in the Black church in the first place.

Still, churches support educational programs and scholarships. They spur local businesses. They bring people together for fellowship. The ramifications of losing a church can ripple through the community.

The grants are key because they give churches the opportunity to invest in capital projects, extending the life of the structure and keeping the doors open, Phillips said.

Another beneficiary is The House of God Church in Nashville, a Holiness-Pentecostal denomination that includes 237 churches. Founder Mother Mary Magdalena L. Tate established the denomination in 1903 in Tennessee.

“This gives our churches a better physical structure and gives them an opportunity for those historic churches to be viable,” said Delvin Moody, program director at the Keith Center, which serves as the historic and preservation grant office for the denomination.

The denomination has always been self-funded, and only recently looked to philanthropic grants for funding. The House of God Church received a $150,000 capacity grant that was used to hire an executive director and cover administrative costs associated with its five-year plan.

They plan to examine the infrastructure of the historic churches in the denomination and develop preservation efforts based on data.

Roughly 85 active congregations are deemed historic and will be aided through the Keith Center’s work “to make sure they’re strong and can plan for the future,” he said.

“They became a physical representation of our history, and when you don’t see the building, or see a building that is dilapidated or not functioning, then you miss the opportunity for younger generations to inquire,” he said. “The role of the Black church is multifaceted.”