Agustín Quiles monitors the anxiety of Florida’s pastors one phone call at a time.

Quiles, who heads an advocacy organization for Latino evangelicals in the state, hears anxiety in the voices of pastors who call him worried about youth who don’t want to go to school, afraid that immigration agents might intercept them. He hears it when pastors say yet another family stopped going to church—it was no longer safe.

He heard it in the pastor who rang him concerned about one of his church’s leaders, an undocumented Colombian national the pastor described as his right-hand man. The pastor said he could never fill the man’s shoes if something happened to him.

And Quiles has heard it when pastors have quietly told him they feel betrayed. They supported Donald Trump because of his conservative stance on issues like transgender rights. But 60 days into Trump’s second presidency, Quiles said, many of those pastors confess to him, “I feel regretful that I made the decision I made, because of what’s happening to my own brothers.”

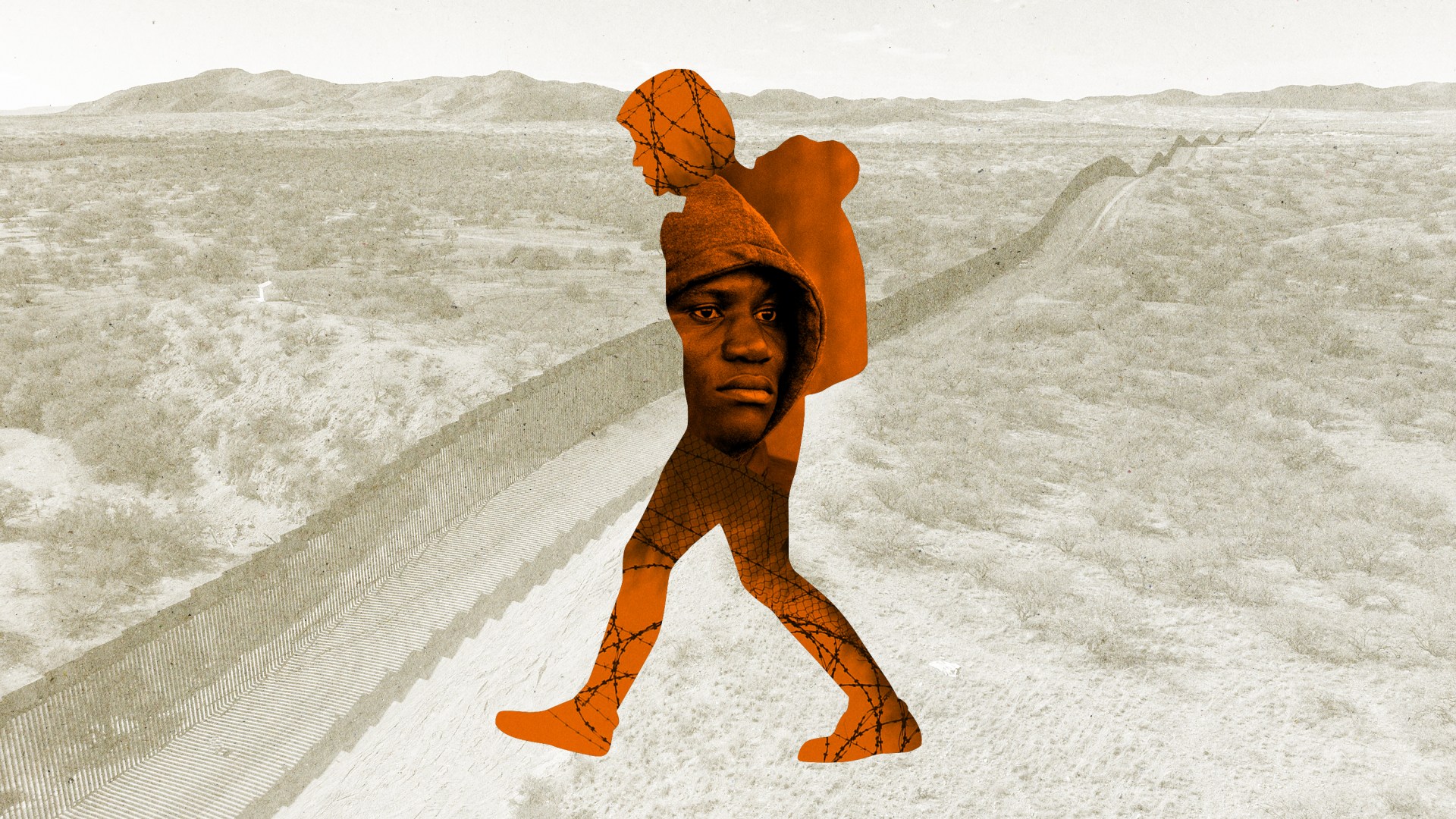

The president’s swift actions to close the US border and deport thousands of immigrants have drawn cheers from supporters across the country, including many evangelicals, while also triggering protests and at least 29 immigration-related lawsuits.

But in Florida, which has become the leading edge of red-state efforts to match Trump’s aggressive policies with hard-line local enforcement, Hispanic church leaders say their communities are living in shock from a double threat.

Florida lawmakers have made a point of outdoing the rest of the country in cracking down on immigrants. In February, Republican governor Ron DeSantis signed a set of bills lawmakers had developed in consultation with the Trump administration.

The new laws make it a crime for undocumented immigrants to enter the state, and they also require local law enforcement to help federal officials detain immigrants. The laws increase penalties for immigrants without legal status who commit crimes—making the death penalty mandatory for those convicted of murder.

“In Florida, there’s a terrible fear,” said Blas Ramírez, a bishop with the International Pentecostal Holiness Church who lives in West Palm Beach and oversees several congregations up and down the state. He estimates that roughly a third of people in his churches are undocumented.

Attendance has dropped, Ramírez said. Venezuelans who might have worshiped in person last Sunday stayed home, for example, absorbing news that federal authorities had invoked an obscure wartime law to deport immigrants. They were processing constant rumors of sweeps by local police and reports that the federal government was flying Venezuelans to a megaprison in El Salvador, accusing them of being terrorists despite family members’ claims that some of them were only guilty of getting tattoos.

“Look, the president is applying a law from the 1800s to undocumented people, a law that applies to enemies of the United States,” Ramírez said. “What is that saying?”

Latino evangelicals overwhelmingly supported Donald Trump during the 2024 presidential election, resonating with his messaging on the economy and traditional stance on issues like abortion and sexuality. Nearly two-thirds of Hispanic Protestants voted for the president, compared with just 46 percent of Hispanics overall. In Florida, the president enjoys more support among Hispanics than he does in other states with large Latino populations.

But when it comes to the president’s immigration actions, some of the state’s Hispanic evangelicals say they are growing disillusioned.

“We agree with the deportation of violent criminals and securing the border,” said Gabriel Salguero, pastor of The Gathering Place, an Assemblies of God church in Orlando. “What we’re concerned about is that, although that’s the rhetoric, that’s actually not what’s happening.”

In fact, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has been arresting more criminals across the country since Trump returned to the White House. During the first few weeks of February, the agency detained well over 20,000 immigrants with criminal records and pending criminal charges—more than it did in any month during the Biden administration, according to government data compiled by Syracuse University.

But those figures may be misleading. ICE scores violations as minor as driving with a broken taillight as criminal convictions; current data offer few clues about how many of those arrested actually committed violent crimes.

The numbers are clear about one trend, however: Arrests of noncriminals are soaring. In the middle two weeks of February, ICE swept up 3,721 immigrants with no criminal record—a 334 percent increase over the first two weeks of January.

Salguero is alarmed by the administration’s use of language that he says lumps all immigrants together and demonizes them. He sees how comfortable White House officials are, for example, labeling as “illegal” migrants who received Temporary Protected Status (TPS), a program created by President H. W. Bush to keep certain groups from being deported to unsafe countries.

“Let’s not play these games saying that TPS people are illegal criminals,” said Salguero, who is also president of the National Latino Evangelical Coalition. “It’s subtle: They started by saying, ‘We’re going after criminals.’ Now they’re saying, ‘All criminals.’ So speeding ticket? Jaywalking? Are you a criminal?”

As Salguero spoke, he rattled off text messages and phone calls he’d received in recent days. A pastor in Tampa had texted him that his church’s guitarist had been arrested, leaving his wife and US-citizen child behind. Leaders from a Pentecostal denomination reached out about a Latino pastors’ event where Salguero was scheduled to speak; they were moving the event online because pastors were afraid to travel.

Latino ministry leaders say they have never seen such elevated fear and vigilance within churches. They attribute much of it to the administration’s decision in January to allow immigration enforcement in churches, an order currently being challenged in court.

Luis Ávila, director of Hispanic ministries for the International Pentecostal Holiness Church, travels the country hearing from pastors of more than 100 Latino congregations in his denomination. Not everyone is paranoid, he said—churches with relatively few undocumented members are carrying on as normal.

Many churches, though, are watching everyone who comes in and out their doors. Worshipers are staying away or streaming services from home. “We’ve been through these kinds of situations before, but never before have we seen what we are going through right now,” Ávila said.

In Florida, Hispanic evangelicals have spoken out before against DeSantis’ support of harsh anti-immigration measures. Churches lobbied successfully to soften the language in a 2023 bill that would have made it a felony to drive a vehicle with undocumented passengers.

But the wins have been few, and ministry leaders say they struggle to reconcile the fact that so many state and national leaders pushing hard-line laws are outspoken about their faith and depend heavily on evangelical support. Last November, more than 80 percent of white evangelical voters in the US cast their ballots for Trump.

“In some ways, it feels for Latino evangelicals as if it’s a persecution,” Quiles said. “It sounds weird, but it’s like, ‘If you’re undocumented, it doesn’t matter if you’re a Christian. You don’t belong here.’”

Salguero pointed to Lifeway Research polling that consistently shows evangelicals want to see the church operating in the spirit of Romans 13, where all are subject to authority, but also in the spirit of Romans 12, not conforming to the pattern of this world. And he said the biblical pattern is clear when it comes to how evangelicals should shape policy toward immigrants: “The overwhelming biblical evidence, from the times of Abraham all the way to Jesus, is that we are to integrate immigrants in a humane way,” Salguero said.

What’s happening now, Ramírez said, appears to him like the exact opposite. The bishop recently met with a Venezuelan pastor and his wife whose fledgling Orlando church fell apart after immigration agents detained several of its members.

The church’s worship team was practicing one day in the clubhouse of a townhome community, according to Ramírez. When the musicians and other church leaders left the practice, agents met them in the parking lot and arrested at least half a dozen of the group. Days later, Ramírez said, agents returned and detained a second group of congregants after they left the clubhouse.

Evangelicals who tolerate aggressive immigration enforcement against noncriminals are “complicit in this unjust action,” Ramírez said. “The church is supposed to defend the oppressed. The church is not supposed to defend the enemy of the oppressed.”

Ramírez, a former lawyer from the Dominican Republic who took evangelism trips to Cuba on his way to full-time ministry in the United States, said he understands a thing or two about oppression. He said he was arrested and imprisoned twice in Cuba in the late 1990s for “preaching the gospel.”

When pastors have to whisper about what’s happening in their churches, when they’re afraid to speak about someone who was arrested, Ramírez said it’s a clear sign that individual liberties are being harmed.

“I thought I’d never see this kind of fear and terror again,” he said. “But people are living it now, here.”

Quiles is especially troubled by Florida’s new mandatory death penalty for undocumented immigrants who commit violent crimes. He’s the president of Mission Talk, a policy group that works with a diverse set of Latino churches in Florida—from conservative Pentecostals to more theologically progressive Cooperative Baptists—to engage them in state policymaking. In addition to lobbying for more compassionate immigration policy, his organization opposes capital punishment.

For several years now, Quiles has led church leaders on trips to Montgomery, Alabama, to study the Civil Rights Movement and America’s dark history of white supremacy.

“I never lived that,” Quiles said. “But it feels like they are trying to go back to those times where you would lynch anyone for any given reason. Is that the same spirit? Is that the same sin that we’ve never dealt with, where we have an obsession with just automatically adding the death penalty to someone who is undocumented?”

Hispanic leaders say they have spent the past two months in countless meetings discussing legal rights and church security, discussing what members need to do to prepare in the event they are detained. Do you have a power of attorney ready? Do you know who will care for your children if you disappear? Who will manage your home and your assets? Identical conversations have repeated thousands of times, in Florida and across the country.

If you pastor a Hispanic church in America right now, Ávila said, you cannot ignore immigration discussions. “It’s part of your life.”

But you also have to pray, he said. He doesn’t want criminals to come into the country, and he agrees that authorities have to stop anyone doing “bad stuff.” But he prays for a way through the mess for the immigrants in his churches.

“I know hundreds of families, and I say to myself, ‘Wow, these people, the only thing they do is good for the country,’” he said. “I see the way they are living, acting, working.”

When he prays for those families, Ávila said, he always starts with this: “Lord, I ask you to sensitize the hearts and minds of these lawmakers.”

Andy Olsen is senior features writer at Christianity Today.