Joseph Bosco Bangura is out to reshape how we think about migrant churches.

For more than 25 years, he has been exploring how new Christian movements open up opportunities to engage with and transform societies. Bangura’s research on the growing Pentecostal movement in his home country of Sierra Leone revealed both its popular appeal and the creative ways charismatic and Pentecostal churches have accommodated indigenous African religious traditions.

Now he’s turning his focus to the impact of migrant churches in Europe. Bangura, who teaches missiology at the Evangelical Theological Faculty (ETF) in Belgium and Protestant Theological University (PThU) in the Netherlands and also pastors a migrant church, spoke with CT about the opportunities and challenges facing migrant congregations in secularized European societies.

What motivated you to study migrant churches in Europe?

There is always a connection between people’s mobility and the spread of their faith. Any time the Jews migrated—in fact, it is from them that we have the term diaspora—something happened to their faith. The same was true in the early church. They didn’t go immediately; persecution brought about their dispersal. Migration inevitably coincides with the spread of the gospel. It widens the possibility of bringing new aspects of the faith to places where they were not initially known.

In Western Europe today, there is a greater awareness among indigenous [i.e., white European] churches of the missionary implications of migrant communities. What can they do for the configuration of the church in a secular Europe? They might be the lifeline for the survival of the faith in a secularized world.

Mission organizations are taking the presence of migrants seriously and are thinking about how to engage them. Harvey Kwiyani, a scholar from Malawi who has written extensively on mission and migration, is working for the Church Mission Society. Leita Ngoy, a native of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) who teaches in Germany, is a consultant for Bread for the World, helping German churches become more welcoming to migrants. The Bible Society for the Netherlands and Flanders (Belgium) has appointed Samuel Ekpo, a Nigerian, as its relationship manager for migrant and international churches.

My own appointment as a professor of missiology at ETF, funded by a Dutch mission organization, and my teaching role at PThU also reflect what is happening. Westerners are realizing that if they want to contribute to the development of global Christianity, they must allow their own academic settings to reflect the diversity in God’s church.

Could you describe what your own congregation looks like?

As a pastor at Exceeding Grace Bible Church in Antwerp, Belgium, I shepherd migrants who want to share their faith. Our 70 attenders reflect a diversity of ethnicities. They are natives of the DRC, Chad, Ghana, Nigeria, and Cameroon. Many are naturalized Belgians. We are fully bilingual in English and French.

We may all be Africans in skin color, but the cultures are different. When we meet or make decisions, we have people representing each of those cultures, so as to present the view that in Christ we are one. We also have various Christian backgrounds—charismatic, evangelical, Catholic. We try to build bridges. It’s a work in progress.

Irrespective of the internal cultural differences, all of us face the same issues that migrants from everywhere face in Belgium: social integration, language, and being considered outsiders who don’t quite belong.

What is the history of migrant churches in Belgium?

As the former colonial power of the DRC, Belgium brought Congolese students to study at Belgian universities even before the DRC’s independence in 1960, intending to send them back as the political elite who would shape the country. But some did not go back. The first migrant church in Brussels was established in the 1980s with support from Campus Crusade for Christ. Belgium subsequently attracted other African migrants—such as Rwandans during the 1994 genocide or West Africans fleeing economic crisis in their home countries—because of its liberal policies for asylum seekers.

Migrant church leaders began to enter into various church organizations, such as the Belgian Evangelical Alliance. More recently, an association was formed to provide fellowship and encouragement for pastors of African and Caribbean origin. Especially in northern Belgium, there are migrant churches in almost all the cities, generally affiliated with local evangelical and Pentecostal associations. The presence of migrant churches has revived the whole concept of Protestant Christianity in this predominantly Catholic country.

What are the different types of churches you see in Belgium?

In my teaching, I describe four categories. There is the migrant church, defined on the basis of the church’s ethnic composition and its difference from the host community. There is the indigenous church, by contrast—although I very rarely hear my Flemish colleagues call their church indigenous. To them, it is just their home church.

Third, there are multicultural churches, where an indigenous church opens up its space to allow cultural fellowships within the church. You may have a white European pastor in charge, but there’s a Filipino fellowship that meets on Wednesday or an African fellowship on Friday. They do their own thing during the week and then all come together on Sunday. That is good, but it raises questions about when the multiculturality of the church will be represented in the leadership structure. When will people of color be able to speak other than on a mission Sunday? The whole vision is often undermined by the lack of diversity in the leadership structure itself.

Finally, there are international churches, which use English exclusively and attract primarily professionals related to NATO, the European Union, Western embassies, or major corporations. Since they are economically independent and able to support themselves, they do not prioritize integration with local Christian communities. The leadership is exclusively white. They too serve a specific group of people who came here as migrants, but because they came as diplomats or corporate elites in the high echelon of society, they are not called migrants.

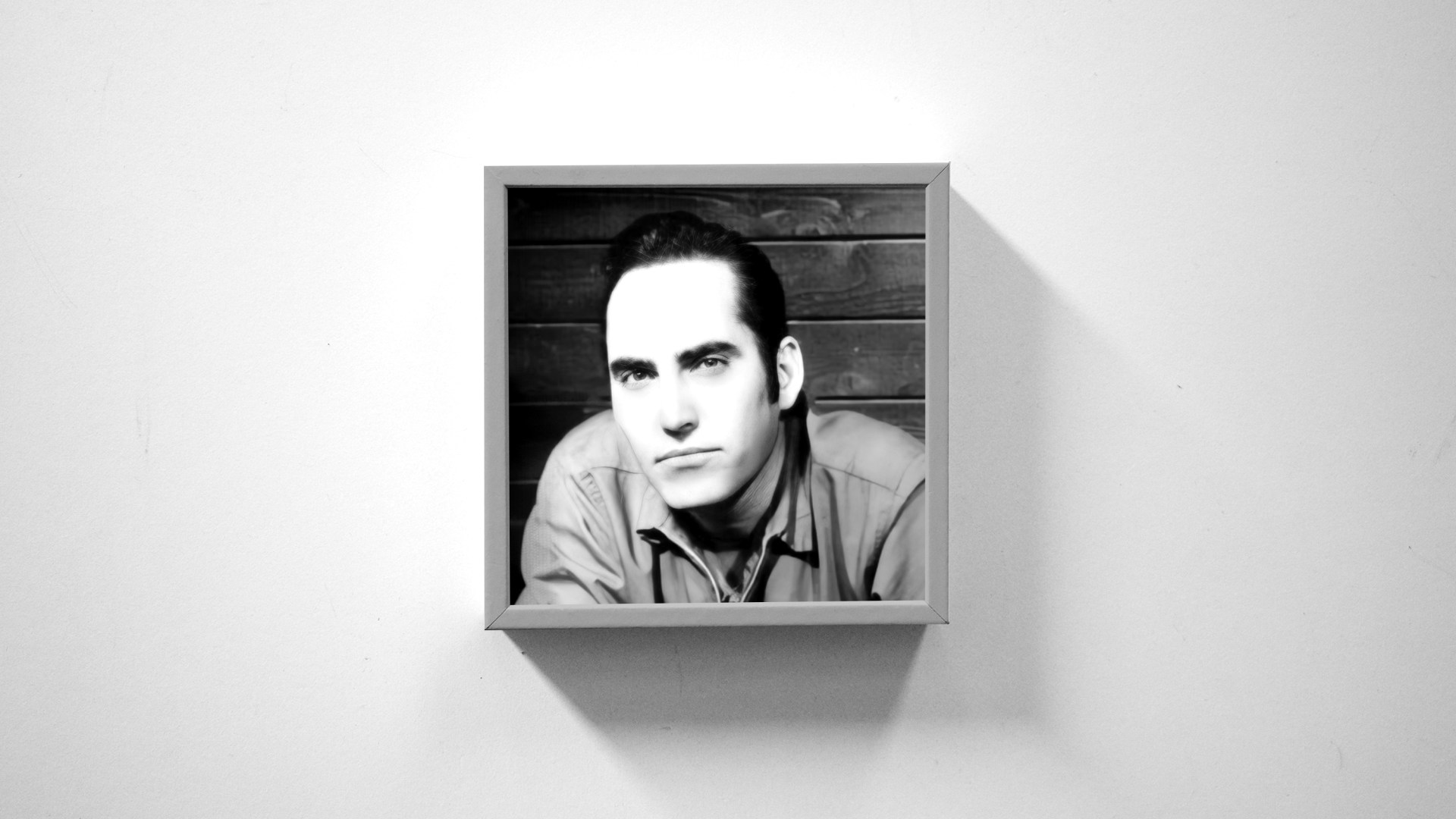

Courtesy of Joseph Bosco Bangura

Courtesy of Joseph Bosco BanguraWhy is it so difficult for multicultural churches to have multicultural leadership?

The idea of having leadership that represents the church’s multiculturality is an excellent goal. I would like to think that such a church would be a good example of what we will experience in heaven. But getting there is quite complicated, with many issues to address.

About 20 years ago, the International Baptist Church in Antwerp was doing well when led by its European founders. When the church was transferred to African leadership, the number of Europeans slowly ebbed away due to concerns that the biblical teaching wasn’t theologically sound enough.

Currently, the whole question of migration is very polarizing in the political sphere. This affects the perception of normal Christians and therefore their ability to collaborate with each other.

Migrant churches are sometimes criticized for focusing only on people of their own ethnicity and keeping the body of Christ segregated. What are your thoughts about this critique?

In 2003, Jan Jongeneel argued that when communities of faith migrate, the initial step, especially with the first generation, is to look inward and meet the needs of members of that community. You must have a base from which to begin missions. We need to give new migrant churches some time to redefine their identity relative to their status in the new society.

The migrant churches are trying to address a missional need. It does not do justice to their cause if we focus on contrasts with other churches. Let’s look instead at how different types of churches can collaborate toward the goal of reaching Europe for Christ.

How do you encourage migrant Christians to integrate effectively with their surrounding culture?

In my church, we encourage families to have their children take an elective subject called PEGO—Protestant evangelical religious education—taught in primary and secondary schools across Belgium. It gives them an idea of how Protestants in Belgium think about faith. Increasingly, people who look like me are teaching this subject. In April, I will be holding a seminar for 400 teachers, talking about African religiosity and how it can help to revitalize religious education in schools. This is an important opening.

I also encourage my African colleagues to participate in local evangelical or Pentecostal fellowships. We may not agree on everything, but we are a minority and cannot afford to stay alone. We should be coming together to share resources and encourage each other. This could help mission not only in Belgium but also from Belgium to the countries we come from. For instance, if a local Belgian church wants to do missions in Sierra Leone, I can provide helpful insights before they get to the mission field.

How do you see the secularity of Belgian culture affecting the second generation of African migrants?

In 2020, I published a chapter reflecting on this issue. Migrant children do not always appreciate the spirituality of their parents. They are also dealing with an identity crisis. Their parents do not consider them Africans at home, but they are considered Africans at school. Collaborating with indigenous churches can help to address some of their needs and give them an opportunity to make a decision for Christ.

First-generation migrant parents are often unable to understand the challenges faced by the second generation, because they still carry with them the spiritual formation they received in Africa. For example, a young lady who had completed secondary school felt the pressure of academic life—from both her peers and her parents—and wanted to take a year off from study. She just wanted to refresh her mind and avoid burnout, but her parents concluded that the devil was interfering with her. How can such parents interpret psychological phenomena in ways that are beneficial to their children? This is a struggle. I hope we can come up with solutions.

Can you summarize how Christians should be thinking about the role of migrants in the church’s mission?

For a long time, migrant Christian communities have been described through the lens of others—of indigenous local communities that still hold cultural dominance. But we ourselves are active mission agents, helping to shape the trajectory of mission in a secularized culture. I appreciate that ETF is invested in new approaches to mission.

When I started studying theology in 1993, the relationship between migration and mission was not on the agenda. As a result, I was not well prepared when I had to migrate. We should be preparing people so that wherever the Lord takes them, for whatever reason, they can consider their migration as God allowing them to spread the gospel to places and among people who have left the faith or are not Christians.

Since you work to bring together Christians of multiple cultures, what would you serve if I came to your home for dinner?

We’d begin with Belgian soup, then have a spiced African rice and cassava leaves dish, and finish with classic Belgian chocolate pudding, all served on a dinner table decorated with braided African tablecloth.