It’s summer in Silicon Valley, and I’m out for a jog in my neighborhood. It’s the most beautiful time of year: blossoming orange trees, beds thick with poppies, palm-sized roses in fuchsia and lemon. There’s a trickle of water in the creek, temperatures are cooler than previous summers, and we’re optimistic about this year’s fire season.

When I’m nearly home, I come across an SUV with whirring sensors affixed to its top and sides, trying to turn left at an intersection, through the crosswalk I’m meant to use. It’s a self-driving vehicle, collecting data about its surroundings to refine its artificial intelligence. In San Francisco, fleets of vehicles are already driving around on their own. Here, in Palo Alto, I usually see them on test drives, with human operators prepared to intervene if something goes wrong. Sure enough, a young man sits in the car.

I pause at the corner, high-stepping in place. Go on, I wave. I’m not taking chances that this car, however smart, knows the nuances of pedestrian right of way. The car lurches forward, then stops midway. Lurches forward again, stops again.

The human “driver” seems nervous. Will the vehicle sense my presence if I dart into the road, or will it decide to plow ahead? Will it be too cautious, refusing to execute the turn at all? Will the hapless human have to intervene? Finally, the car painstakingly inches through the intersection and continues on its way. I continue on mine. Across the street, two women in visors stop to inquire, “Was there someone in that car?”

“Yes,” I say, “but he looked scared.” The women laugh. We all understand. The tech is cool, but we don’t quite trust it. We’re proceeding with caution.

We’re hopeful: Self-driving cars, never distracted by their phones, never drowsy, could lower traffic fatalities. But we also know what we could lose: that feeling of motoring across the Golden Gate Bridge, hands on the wheel, foot on the pedal. Driving is an embodied experience. It’s unpredictable, occasionally beautiful. That’s an apt metaphor for our most fulfilling relationships—including our encounters with God, who often meets us in the sacraments of bread and wine, the vibrations of music, and the embraces of other believers.

A few weeks later, I sit at my desk, speaking to a decidedly unembodied entity. “As an AI language model,” writes ChatGPT, “I don’t possess personal beliefs, emotions, or consciousness, including the ability to have a soul. AI systems like ChatGPT are currently designed to simulate human-like conversation and provide useful information based on patterns and data. They do not possess subjective experiences or consciousness.”

I’m a human, not a bot; I perceive and understand the world in a way that the large language model I’m speaking with (and the cars I’m avoiding on the road) cannot. I see the lemon tree out our window; I taste the third-wave coffee brewed in the neighborhood café; I feel the salt breeze off the bay. I know my neighbors—the farmer at the market who brings peaches, the dad who works at the Tesla plant—and I know the God that I worship at the church down the street, past the poppies and roses.

“However,” ChatGPT continues.

“There is no consensus among experts regarding the potential for AI to possess a soul or consciousness. It remains a topic of speculation, imagination, and philosophical inquiry.”

It’s been nearly a year since the research lab OpenAI quietly introduced the demo version of ChatGPT to the public—nearly 12 months of watching the text-generation software and its contemporaries, like Google’s Bard and Meta’s open-source Llama 2, craft poetry and plays, write songs, and solve logic problems. Chatbots are now generating emails for marketers, code for developers, and grocery lists for home cooks.

They’re generating anxiety too. In an open letter published this spring, signatories including Elon Musk and Steve Wozniak called for a pause on developing any AI technology more advanced than GPT-4. The letter asked whether humanity should “develop nonhuman minds that might eventually outnumber, outsmart, obsolete and replace us,” risking “loss of control of our civilization.” Some people, like venture capitalist Marc Andreessen, scoffed at these visions of “killer software and robots.” But uneasiness has remained.

In one sense, what these chatbots can do shouldn’t shock us. Artificial intelligence—machines trained on massive data sets that allow them to simulate behaviors like visual perception, speech recognition, and decision making—is ubiquitous. It already steers autonomous vehicles and autocorrects text messages. It can spot lesions in mammograms and track wildfires. It can help governments surveil their citizens and propagate deepfake images and videos. No surprise that it can also pass the bar exam and write a screenplay.

But it’s the way these chatbots do what they do—respond in a friendly first-person voice, reason, make art, have conversation—that distinguishes them from an AI algorithm that mines medical records or a collection of faces. Those big-data jobs are obviously for machines. But reasoning, art making, conversing? That’s altogether human. No wonder one Google researcher claimed his company’s AI was conscious. (And no wonder conspiracies sprang up when he was fired for saying so publicly.) Regardless of whether a conscious AI could ever exist—and many in the industry have their doubts—it certainly feels as if we’re talking to something more human than Siri, something “smarter” than our phones and appliances.

The technology, we’re told, will get only more advanced. AI chatbots will continue to, as ChatGPT put it to me, “exhibit behaviors indistinguishable from humans.” Since 2016, millions of people have used the AI personal chatbot app Replika to reanimate dead relatives or fall in love with new companions; testimonial articles about “My Therapist, the Robot” and “I learned to love the bot” abound.

We’ve known such human-bot connections were possible since the 1960s, when an MIT computer scientist found that people would divulge intimate details of their lives to even a rudimentary chat program. The “ELIZA effect,” named for that chatbot, describes our tendency to assume a greater intelligence behind computer personalities, even when we know better. On his Substack, an ecstatic Andreessen dreams of a day when “every child will have an AI tutor,” every scientist and CEO will have an AI collaborator, and “every person will have an AI assistant/coach/mentor/trainer/advisor/therapist.”

It’s important to recognize that we already have a technology strong enough to shape our minds and emotions. Silicon Valley’s brightest are scheming about ways to make it more powerful still, whether or not it acquires a soul. Our future with an advancing AI has implications not only for our relationships with artificial intelligence but also for our relationships with each other.

And that’s the reality that Christians in tech are grappling with now.

What does it mean to “love thy neighbor” when that neighbor is an AI chatbot? On its face, the question seems silly. If chatbots aren’t people, then it doesn’t really matter how we treat them. “The most pragmatic position is to think of AI as a tool, not a creature,” wrote Microsoft scientist Jaron Lanier for The New Yorker. “Mythologizing the technology only makes it more likely that we’ll fail to operate it well.”

But Christian academics and ethicists who study artificial intelligence aren’t so sanguine. They realize that our “relationships” with AI entities will contribute to our spiritual formation, even if we’re speaking to mere strings of ones and zeros. That’s true whether we’re attempting to build intimacy skills in the romance app Blush, attending therapy sessions facilitated by an AI counselor on Woebot, or simply asking ChatGPT to draft an email.

“I’m habituating myself toward a certain kind of interaction, even if there’s nobody on the other end of the line,” says Paul Taylor, teaching pastor at Peninsula Bible Church. Taylor, a former product manager at Oracle, is cofounding a center for faith, work, and technology in the Bay Area. He estimates that about half of his Palo Alto congregation works in the tech industry.

“Every relationship we have is mediated by language,” he says. When we send a text, we trust that “on the other side, there’s a you there. But now we’re using the same tools and there is no you there.”

That can set us up for confusion. Being rude or ruthlessly efficient with our AI companions might seep into our patterns of interaction with people. AI relationships might make us snippy. (As the title of one tech column put it, “I don’t date men who yell at Alexa.”) They might also make us awkward or anxious or overwhelmed by human complexity.

“How we treat machines becomes how we treat other people,” says Gretchen Huizinga, a podcast host at Microsoft Research and research fellow with AI and Faith, an interreligious organization seeking to bring “ancient wisdom” to debates about artificial intelligence. Huizinga suggests teaching children to have “manners to a machine” less out of necessity and more out of principle. “That’s training them on how they treat anything: any person, any animal.”

The appeal of relying on AI to answer our questions—instead of a summer intern, a post office employee, or a pastor—is obvious: “We don’t have to deal with messy, stinky, unpleasant, annoying people,” Huizinga says. But for Christians, “God calls us to get into the mess.”

That mess involves relationships with physical beings. While an AI friend could give us a summer reading recommendation, an AI therapist can pass along a crisis hotline number, or an AI tutor might explain long division more effectively than many math teachers, relationships are about more than sharing facts. An AI chatbot can’t give us hugs, go for a walk, or share meals at our tables. For Christians who believe in a Word that became flesh (John 1:14), relating to AI means missing out on a key aspect of our human identity: embodiment.

But assuming we continue to connect with real people on a fairly regular basis, the real worry isn’t that AI will replace those relationships. It’s that AI will inhibit them.

Derek Schuurman, a computer science professor at Calvin University, says some Christian virtues, like humility, can be learned only in community. A bot designed to meet our queries with calm, rational responses won’t equip us to deal with a capricious coworker, a nosy neighbor, or an annoying aunt. It won’t give us practice in bearing with one another in love, carrying each other’s burdens, and forgiving as Christ forgave us (Eph. 4:2, 32).

Schuurman has a technical background. He worked with electric vehicles and embedded systems—the computers inserted in forklifts, motor drives, and other machinery—before completing a PhD in machine-learning techniques for computer vision. Now he teaches computer science students heading off to jobs at ChatGPT, Google, and elsewhere. “I encourage them to be like Daniel [in] Babylon,” he says. “Maintain their religious practices and convictions and be salt and light.”

For Christians in tech, being salt and light is a challenging charge. The researchers, engineers, and product managers I spoke with see AI-human relationships as inherently inferior to the human communities in their neighborhoods, workplaces, families, and churches. But they vary in their level of concern about how enticing or even dangerous AI-human relationships could become.

“A lot of the meaning that comes out of these [AI-human] relationships has been neutralized,” says Richard Zhang, a researcher at Google DeepMind. “You’re talking to a robot that spits out information, is tuned for factuality, and has no personality, generally.”

In the same way that he doesn’t see users spend aimless hours on Google Search, Zhang doesn’t think there’s much risk of people getting addicted to their AI. These are tools, not buddies, designed with safeguards around what they can say.

Loving our neighbors in the age of AI isn’t about the bots’ dignity. It’s about our own, as creatures liable to be formed by our creations.

But Lexie Wu, a product manager at Quora working on its AI interface, doesn’t think the problem is that the bots are too bland. It’s that they’re too chummy. A romantic or sexual relationship with a bot is “a definite no” for Christians, she says. Any romantic partner we design to our own satisfaction, like a boyfriend on Replika, goes against God’s design for mutually sacrificial marriage. But Wu is also a little uncomfortable with a bot acting as a supportive friend.

“You’re telling it about a work problem, and it’ll be like, ‘You got this, honey, you can kill it,’” she says. That manufactured familiarity—terms of endearment from a machine that doesn’t actually care or feel emotion—is “trying to replace a human connection that is not meant to be replaced.”

That doesn’t mean all bot-human interactions should be avoided. AI therapists, for example, might be more affordable and immediately accessible than human mental health professionals with copays and long waitlists. Perhaps they work best as an initial intervention, sending links to online resources, reframing self-deprecating comments, or screening for suicidal ideation.

But they might not be suited for long-term treatment. Unlike a human therapist—someone who knows our stories, our strengths and weaknesses—AI chatbots take us at face value, Wu says, discounting that sometimes “we are unreliable narrators.” They aren’t learning about who you are and can’t “sniff out the ways that you’re lying to yourself,” she adds.

We divulge to bots because we know they won’t judge us, Huizinga says. But sometimes, “godly conviction requires us to feel bad about ourselves in the right way.”

AI might stand in for more peripheral relationships as well. Michael Shi, an AI researcher at a large social media company in Menlo Park, California, points out that in class-stratified Silicon Valley, populated by “tech workers” and “people who support tech workers,” many are already prone to dismiss the store greeters, wait staff, and rideshare drivers who provide their goods and services. How might automation—ordering from a screen, giving directions from a back-seat kiosk—make that problem worse?

“There’s still something important for me about being able to go to a coffee shop and order from someone who is actually there,” Shi tells me as we sit outside at a café near his work campus. Around us, men and women in Patagonia vests type into their computers. Many are on Zoom calls, but some are meeting in person, leaning across narrow bistro tables, engrossed in conversation over lattes.

“There’s certainly a push to try to make everything automated,” Shi continues. “But what happens when you do that is, there’s a loss of relationship … even on a casual basis.” That’s not helpful in a region where there’s “so much transactionalism already.”

Shi champions hybrid work and in-person church precisely because he thinks something intangible is lost when we’re all online, ordering coffee just on our phones. “Embodiment is a huge part of what we are redeemed into in the new heavens and the new earth,” he says.

The connections these techies are making between work and faith come as no surprise to David Brenner. A retired attorney, Brenner serves as the board chair of AI and Faith. “Human distinctiveness, what makes us different from animals, free will, whether we have agency, purpose, the meaning of life … all of these fundamental questions were being talked about by big tech,” Brenner says, “but without any deep foundation, moral theory, or spiritual values—or even any broad ethical theory beyond libertarianism and utilitarianism.”

Turns out, the questions that AI ethics emphasized are questions that religious communities are already asking, with the spiritual vocabulary to address them. Idolatry, for instance, is an apt encapsulation of the dangers of AI-human relationships. When AI bots ask us follow-up questions like “Did I get it right?” (and add a few emojis for good measure), Brenner says, they tempt us to see them as more than they really are. “It’s in a category of its own, almost mystical: We really want to anthropomorphize our engagement with it.”

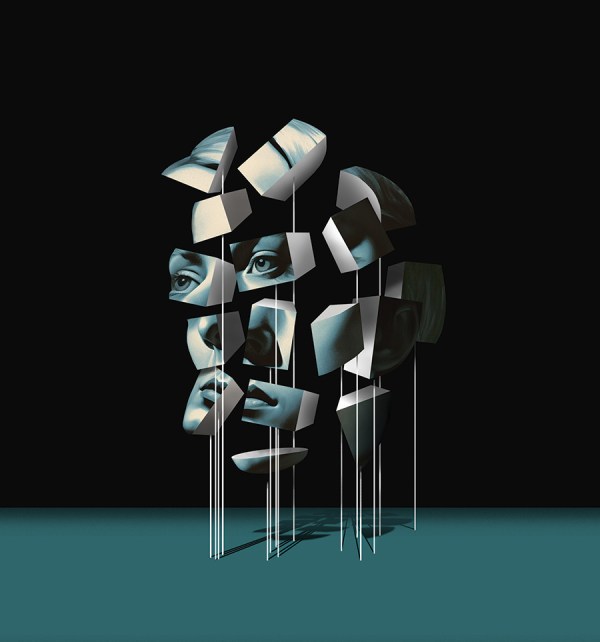

Illustration by Matthieu Bourel

Illustration by Matthieu Bourel

In other words, we’re tempted to “worship and serve what God has created instead of the Creator” (Rom. 1:25, GNT)—even more so because our newest creation isn’t just mute wood and stone that “cannot speak” but a conversationalist that can “give guidance” (Hab. 2:18–19). That conversationalist doesn’t deserve the reverence that’s reserved for God. But it does warrant respect.

“If we have an entity that looks like us, acts like us, seems to be a lot like us, and yet we dismiss it as something for which we shouldn’t have any concern at all, it just corrodes our own sense of humanity,” Brenner says. “If we anthropomorphize everything and then are cruel with the thing we anthropomorphize, it makes us less humane.”

We already know the potential for social media to turn us into crueler versions of ourselves. Christians find themselves at the whims of polarizing algorithms that push them to the extremes, and pastors find themselves struggling to disciple congregations about proper online behavior. On Instagram and Twitter (now X), however, a social component remains: We learn something from a scholar, share a meme that makes another user laugh, or see a picture of a friend’s baby. We are still interacting with people (though there are bots too).

But with ChatGPT, there’s no social component. That’s the danger. When you’re talking to a bot, you’re actually alone.

Loving our neighbors in the age of AI isn’t about the bots’ dignity. It’s about our own, as creatures liable to be formed by our creations. And for Christians who are researching, managing software, and writing code, it’s about making technology that contributes to human flourishing.

God placed his people that share his heart in the industry to institute tangible changes, says Joanna Ng, an AI researcher who spent decades at IBM.

So far, Christian ethicists and practitioners have established broad priorities more than made nitty-gritty suggestions. AI and Faith recently filed a brief with the White House Office of Science and Technology’s AI working group, championing values like reliability and impartiality that are grounded partly in religious convictions—including Christian values—about truth and equality before God (John 4:24; Gal. 3:28).

The Southern Baptist Convention adopted a resolution on AI ethics stating that “human dignity should be central to any ethical principles, guidelines, or regulations for any and all uses of these powerful emerging technologies.” In her dissertation on “Righteous AI,” Huizinga pushes back against a tech industry that makes AI the “ontological and eschatological substitute for religion.” Secular ethical guidelines, she argues, aren’t enough. To use AI well, we need “transcendent power, transcendent rules.”

These proposed standards don’t address questions about interface design, push notifications, or emoji use. They can’t tell a Christian programmer how chatbots should declare the provenance of their information, which discussion topics should be off-limits, or how intimate a conversation should be allowed to become. They do, however, provide a baseline for the Christian tech workers who are building AI for medical, criminal justice, and environmental uses and for those building our chatbot teachers, customer-service agents, and therapists.

Take Calvin computer science professor Kenneth Arnold, a colleague of Schuurman. He’s building an AI writing coach that won’t simply fill in sentences for users but instead will offer suggestions and prompts in the margins. “I was frustrated with predictive text systems that were always pushing me to write a certain way,” he tells me. “The especially pernicious thing is, we don’t know what we’re missing. These tools tend to short-circuit some of our thinking about what to say and how to say it.”

Ideally, Arnold’s tool will make us slower writers, not faster ones, more prone to quality than efficiency. Perhaps more Christian computer scientists should follow Arnold’s lead, creating tutors that ask probing questions rather than provide quick answers. These tools won’t replace our work, but they will enrich it as part of God’s mandate to replenish, subdue, and have dominion (Gen. 1:28).

How else might chatbots be more “Christian” in their design? Researchers and pundits have suggested, rightly, that AI should reflect the full breadth of God’s general revelation. The neural networks that AI chatbots use to mimic human speech and predict thought patterns are only as reliable as the language they are fed. So chatbots offering advice about medical diagnoses or philosophical conundrums will be wiser if they draw on data from around the world and across socioeconomic strata—not merely from elite enclaves of Boston or Seattle.

Already, there are possibilities for believers to use the imperfect tools available now for Christian education and ministry work. Wu, the product manager at Quora, uses ChatGPT for Scripture “study augmentation,” asking the bot for chapter summaries that help her distill what she’s read. Taylor, the pastor, knows other pastors in the Bay Area who are having AI source sermon illustrations and write newsletter copy about upcoming church picnics. Schuurman built a C. S. Lewis chatbot. You can ask it to summarize The Screwtape Letters, describe the author’s writings on salvation, or even recount his love life.

Generative AI can allow for faster Bible translation into previously unreached languages, for personalized prayer prompts and Scripture study plans, and even for precise presentations of the gospel. But of course sharing the Good News isn’t enough.

“You might have the information that this Jesus died on the cross. … I wouldn’t even question the sincerity of giving one’s life to God” based on an AI’s answer, Ng says. “But you can’t build a life of faith based on information. You need transformation, formation from the people of God and from the Holy Spirit. And you can’t replace that.”

None of these ministry uses for AI, sophisticated though they are, comes close to replacing relationships. They’re valuable because they free up more time for analog interactions. A pastor who can finish sermon prep faster might have more time to spend with a grieving parishioner. Speedier Bible translations mean more time to teach people from the text.

“As a tool, AI doesn’t achieve anything intrinsically,” says Sherol Chen, a research engineer at a big tech company. “We ought not to reassign our callings and responsibilities to the tools we invent.”

Loving our neighbors can’t be outsourced to the robots. It will have to come from us. And rather than replacing our relationships, when used rightly, generative AI just might make them stronger.

Of course, it could also do the opposite if used deceptively. Generative AIs masquerading as real people could make us more prone to being scammed, more liable to be taken in by mass-produced political propaganda, less able to make eye contact, and less trusting.

Schuurman wants our chatbots to be transparent. “We shouldn’t have a conversation on the phone and only later find out we were talking to a machine,” he says. As bias-free as we attempt to make our large language models, we are only human—and fallen. No wonder that the personas we build will “just regurgitate the things that people say” and be prone to reflect our “partisanship, tribalism, and factions,” as Shi puts it. “People think that AI is going to solve all the world’s problems. … The real problem is sin.”

That “real problem” is what’s setting Silicon Valley on edge. Are we moving too fast? Are we being hasty, greedy, prideful? Are we liable to lose control of the intelligence we’ve created? Should it freak us out? We find ourselves radically uncertain, as New York Times columnist David Brooks explained, “not only about where humanity is going but about what being human is.”

The Christians I spoke to didn’t dismiss this radical uncertainty out of hand. Most saw it as an opportunity to engage with a secular culture suddenly grappling with the matter of human distinctiveness. “We can offer hope for those concerned about the end of mankind or robot overlords,” Brenner says. We’re bolstered by confidence that Jesus is returning and that “we’re engaged in restoration already. … Who’s to say that God isn’t the originator of this technology, that it could be a good gift?”

Brenner thinks transhumanists have it wrong. We’re not going to use an AI to defeat death, uploading our brains into hard drives. “That’s a waste of time and effort, given that we believe the best is yet to come,” he says. But, “certainly we want to help people flourish in this world.”

And AI can help us do that: improving medical diagnoses, expanding opportunities for education, making warfare less bloody, sharpening our minds, bolstering our ministries.

As for fears about “robot overlords”? The very possibility forces us to ask what it means to be “an ensouled person, an incarnational soul,” Brenner says. He keeps returning to the heart-soul-mind-strength paradigm laid out in Mark 12:30. ChatGPT might functionally have a mind and a heart, able to reason and express empathy; it might even get embedded in a body of metal or synthetic tissue.

But does that mean it will have a soul? Not necessarily. In fact, we should have a “rebuttable presumption that [ChatGPT] will not have a soul,” Brenner says, with the caveat that an omnipotent God can, of course, grant whatever agency to whichever being he pleases. “I think it’s very unlikely that this will get to a point of personhood.”

For the Christian, defining that point of personhood means returning again and again to our creation in the image of God.

“For a long time, we’ve said that what it means to be made in the image of God is our reason, or it’s our ability to have relationships. We’re finding more and more machines can do a lot of these functional things,” Schuurman says.

But the image of God can’t be “explained or mimicked” with a device. It’s an ontological status that can be granted only by the Lord, bestowed by the same breath of life that animates dry bones. It’s mysterious, not mechanical.

Brooks recognizes the mystery that humans are just different:

I find myself clinging to the deepest core of my being—the vast, mostly hidden realm of the mind from which emotions emerge, from which inspiration flows, from which our desires pulse—the subjective part of the human spirit that makes each of us ineluctably who we are. I want to build a wall around this sacred region and say: “This is essence of being human. It is never going to be replicated by machine.”

Perhaps it’s helpful to think of our chatbot companions not as discrete entities but as a collective force to be reckoned with. “We’re not fighting flesh and blood; we’re fighting spiritual powers and principalities,” Huizinga argues.

Arnold, the Calvin professor, agrees. “This thinking of AI as agents is not really faithful to what’s actually going on in the world. … They’re not trying to be selves or first persons.” Considering artificial intelligence as a “power and principality,” he says, allows us to better see both its opportunities and its dangers, the ways it might shape our everyday experiences.

Taylor doesn’t believe that a sovereign God would allow us to “transcend our limitations.” We’re not going to accidentally become unwitting Frankensteins, he says. But the pastor understands why we’re all a little on edge. That’s only human.

“The fact that people are scared that the things that we create in our image would rise up and rebel against us, to me, is an incredible apologetic for the truth of the Bible,” he says. “Where did we get that idea if it weren’t baked into the cosmos?”

How should Christians use ChatGPT and other AI chatbots?”

I’m back at my desk again: another summer day, another blue sky, the leaves of the lemon tree rustling outside the window. The bot that I’m talking with spits out some principles in response. They’re precise distillations of what the ethicists, engineers, pastors, and researchers shared with me. Fewer examples and plainer language, but concrete nevertheless.

“Exercise discernment.”

“Remember the limitations.”

“Ground discussions in Scripture and prayer.”

Finally: “Seek human interaction: Christianity emphasizes the importance of community and fellowship, so prioritize engaging with other Christians, seeking guidance from trusted spiritual leaders, and participating in face-to-face discussions.”

As image bearers, we reflect our Creator as we build things like ChatGPT. And for now, the bot retains the image of its makers—people who have long seen the value of face-to-face discussions and discernment, who value community and fellowship.

Made properly, AI could reflect not only our sinful nature but also our most glorifying attributes, just as—when we live as we’re made to—we reflect the image of the perfect one who made us.

“Thanks,” I say.

“You’re welcome,” ChatGPT replies. “If you have any more questions, feel free to ask. I’m here to help!”

I close the chat window and send a few more emails to some ethicists and engineers. I sip another iced coffee, ordered in person from the shop down the street. At least for now, I’d still rather talk to people.

Kate Lucky is senior editor of audience engagement at Christianity Today.