The United States operated 408 boarding schools for indigenous children across 37 states or then-territories between 1819 and 1969 — half of them likely supported by religious institutions.

That’s according to the first volume of an investigative report into the country’s Indian boarding school system that was released Wednesday by the US Department of the Interior.

“Our initial investigation results show that approximately 50 percent of federal Indian boarding schools may have received support or involvement from religious institutions or organizations, including funding, infrastructure and personnel,” Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland said at a news conference on the progress of the department’s Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative.

The report revealed nearly 40 more schools than the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition previously had identified in the US—and nearly three times more than the number of schools documented in Canada’s residential school system by that country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

It also identified marked or unmarked burial sites at more than 50 schools across the Indian boarding school system. The department expects that number to go up as it continues to investigate.

And it described an “unprecedented delegation of power by the Federal Government to church bodies.”

The Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative was announced last summer by Interior Secretary Deb Haaland to investigate the history and lasting consequences of the schools. That announcement came as indigenous groups across Canada confirmed the remains of more than 1,000 indigenous children buried near former residential schools for indigenous children there.

The Department of the Interior was “uniquely positioned” to undertake such an initiative, the secretary said at the time in a memorandum, because it had been responsible for operating or overseeing the boarding schools.

From 1819 through the 1960s, the US implemented policies establishing and supporting Indian boarding schools across the nation. The report released Wednesday includes the first-ever inventory of those federally operated schools, including profiles and maps of each school.

The boarding schools supported a “twin United States policy” to culturally assimilate Native American, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian children and to seize indigenous land, according to Newland, a citizen of the Bay Mills Indian Community (Ojibwe).

“The report explains that the federal government pursued this policy of forced assimilation by targeting Indian children. Federal Indian boarding schools were the primary means to carry out this policy, and the report shows that all three branches of the federal government impacted the system,” he said.

Generations of children were “induced or compelled by the federal government” to attend the schools, which separated them from their families, languages, religions and cultures, he said.

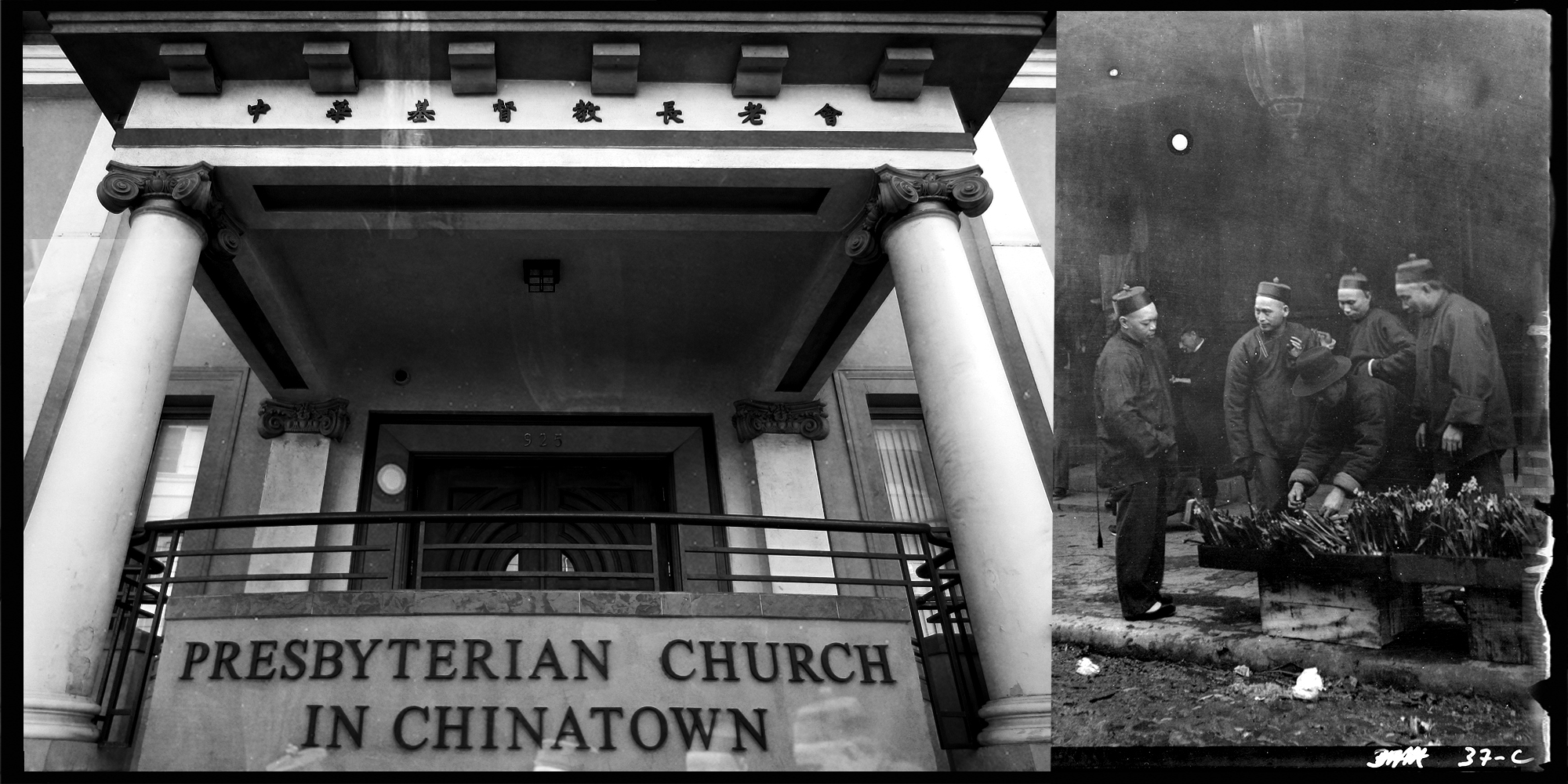

The schools attempted to assimilate children in a number of ways, including giving indigenous children English names, cutting their hair, even organizing them into units to perform military drills, according to the report. They discouraged or prevented children from speaking indigenous languages or from engaging in their own spiritual and cultural practices.

Many children endured physical and emotional abuse. Some died.

“The consequences of federal Indian boarding school policies—including the intergenerational trauma caused by forced family separation and cultural eradication, which were inflicted upon generations of children as young as 4 years old—are heartbreaking and undeniable,” said Haaland, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna and the first Native American to serve as a Cabinet secretary.

The Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative’s work included collecting records and information related to the department’s involvement in the Indian boarding school program and consulting with tribal nations, Alaska Native corporations and Native Hawaiian organizations.

It also partnered with the National Boarding School Healing Coalition.

Deborah Parker, a citizen of the Tulalip Tribes and chief executive officer of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, said their collaborative work had identified nearly 500 boarding schools total, including another 89 that received no federal funding.

“This is a historic moment as it reaffirms the stories we all grew up with, the truth of our people, and that often immense torture our elders and ancestors went through as children at the hands of the federal government and religious institutions,” Parker said.

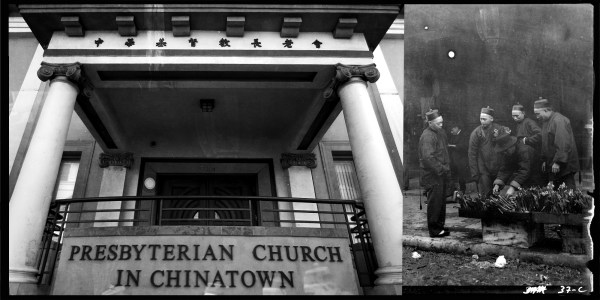

The Roman Catholic Church and a number of Protestant denominations—including Methodists, Episcopalians, and Presbyterians—already have begun investigating their own roles in those boarding schools.

The Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative report explained that the government divvied up reservations among “major religious denominations.”

Those religious institutions and organizations were able to nominate new agents and direct educational and other activities on the reservations. They also were given tracts of reservation land to use for educational and missionary work and, at times, paid per capita for each indigenous child who entered the schools they operated.

Several Catholic groups and Protestant denominations also have called for the United States to establish a Truth and Healing Commission similar to Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which issued its final report on its own residential school system for indigenous children in 2015. The Protestant supporters include the Christian Reformed Church of North America’s Office of Race Relations, the United Methodist Church’s General Board of Church and Society, the Episcopal Church, and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

They’re joined by lawmakers, who reintroduced the Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies in the United States Act last year.

The act would create a commission to investigate, document and acknowledge the past injustices of US boarding school policy. A US commission also would develop recommendations for Congress to help heal the historical and intergenerational trauma passed down in Native families and communities and provide a forum for boarding school survivors to share their experiences.

At Wednesday’s news conference, Parker reiterated the call for a Truth and Healing Commission.

“We must be able to locate church and government records beyond the Department of Interior’s reach,” she said.

Other speakers outlined next steps for the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative.

Newland said the next volume of the initiative’s report will approximate the total number of children that attended boarding schools, the amount of federal support for this system and the total number of marked and unmarked burial sites at schools. It also will attempt to identify the names, ages and tribal affiliations of children interred at those burial sites.

And Haaland announced the launch of “The Road to Healing,” a yearlong tour of the country to give American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian survivors of the federal Indian boarding school system the opportunity to share their stories. It also will help connect communities with trauma-informed support and facilitate the collection of oral histories.

“This is not new to us,” Haaland said.

“It’s not new to many of us as indigenous people. We have lived with the intergenerational trauma of federal Indian boarding school policies for many years. But what is new is the determination in the Biden-Harris administration to make a lasting difference in the impact of this trauma for future generations.”