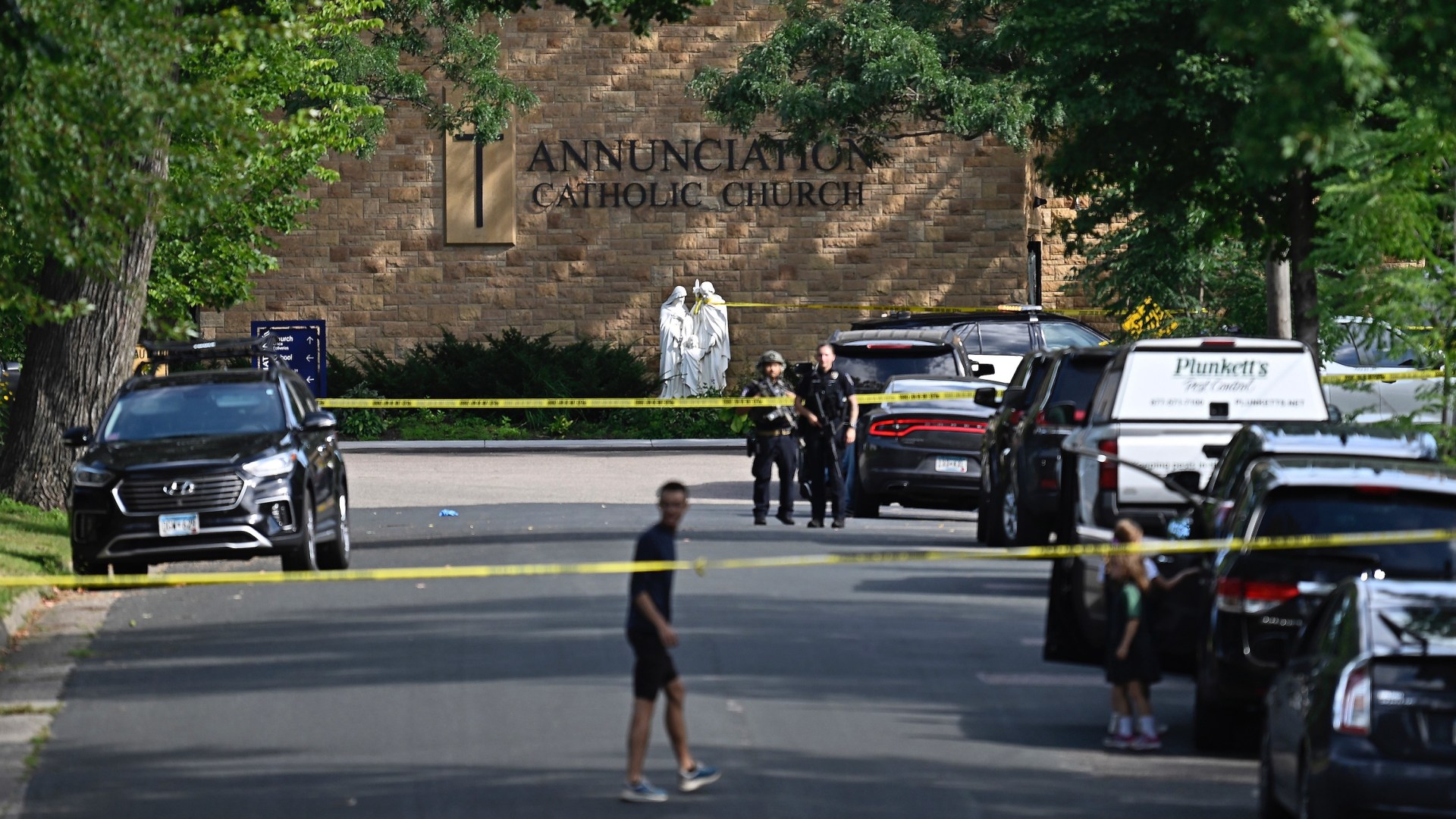

Churchgoers between the ages of 18 and 28 attend church more frequently than their older siblings, parents, or grandparents. A new study, part of the State of the Church research initiative from Barna Group and Gloo, found a post-pandemic surge among Gen Z churchgoers over the age of 18.

Today, when people born between 1997 and 2007 go to church, they attend, on average, about 23 services per year. Churchgoing Gen Xers, in contrast, make it to about 19 out of 52 Sundays, while Boomer and Elder churchgoers average just under 17, Barna found.

Millennial churchgoers, born between 1981 and 1996, attend 22 services annually, up from a previous high of 19 in 2012.

The Barna study, released today, calls this a “historic” and “generational reversal.”

“The fact that young people are showing up more frequently than before is not a typical trend,” Daniel Copeland, Barna’s vice president of research, said in a statement. “This data represents good news for church leaders and adds to the picture that spiritual renewal is shaping Gen Z and Millennials today.”

Barna’s research, based on 5,580 online surveys done between January and July, does not look at the overall decline of the number of people going to church in America, however. A recent Pew Research Center study found that just 45 percent of adults under 30 attend religious services—a number that seems to have dropped nearly 20 points in 10 years, although comparisons are inexact.

It is possible that the frequency of Gen Z church attendance has increased in the last five years because less-committed, less-regular churchgoers have simply stopped going. Perhaps the ones who still go, are more likely to go more.

Older generations, meanwhile, are going to church less frequently even when they still attend, Barna’s data shows.

“In our collective memory, we have this memory that people attended church every week—twice on Sundays, Sunday school, and midweek services. The data is telling us there has been a shift,” Barna CEO David Kinnaman told CT. “The data helps us recognize the elephant in the room: When people are in church, they’re going about every two out of every five weekends.”

Barna’s study found that churchgoers born before 1946 are attending, on average, 11 fewer services in 2025 than they did in 2000. Churchgoers born between 1946 and ’64 are at church 7 fewer Sundays every year. That’s between one and a half and three months of skipping church.

And large numbers of older people have stopped going altogether. Although Pew says direct comparisons are problematic because polling has shifted from phone calls to internet surveys, a 2007 study showed that about 22 percent of people over the age of 65 seldom or never went to church. In the most recent survey, that number was up to 40 percent.

If that’s right, then 18 out of every 100 senior citizens quit participating in religious services sometime in the last two decades.

“One of the larger trends in social research on religion that we see is a winnowing the wheat from the chaff as nonpracticing Christians are tiptoeing toward identifying as ‘nones,’” Kinnaman said. “That’s one reason it’s so remarkable to see younger generations saying, ‘I don’t think we’ve given religious communities enough of a chance.’”

When COVID-19 restrictions lifted, many churchgoers seemed to reevaluate what they wanted to do with their Sunday mornings.

Barna found that Gen X attendance returned to pre-pandemic levels—and increased slightly from start of the century. Today, Gen X churchgoers average 1.6 services per month.

Millennials’ church attendance has also gone up, according to Barna. Today, churchgoers between the ages of 29 and 44 average 1.6 services per month—going to church about six or seven more Sundays per year than they did in 2000.

Barna researchers think this data will confirm the intuition many pastors have about shifting demographics, with younger people coming more often, and average attendance rates, how often people show up. The study notes that many pastors feel frustrated by irregular attendance and find it hard to build momentum in their congregations.

At the same time, the church-tech company Gloo wants Christian leaders to see new possibilities.

“These shifts in church attendance open the door for leaders to innovate,” Gloo president Brad Hill said. “Churches that prioritize relational touchpoints and digital engagement—through text, social media and other online tools—can better reach younger generations where they already are.”

Kinnaman hopes the data will help church leaders be proactive and encourage them to focus on how they can best meet people’s spiritual needs.

“The fabric of congregational life is changing,” he told CT. “We really need to grapple with the learning needs, the content needs, of younger generations and how we’re structuring discipleship and teaching calendars and building communities when people are at church two out of every five Sundays.”