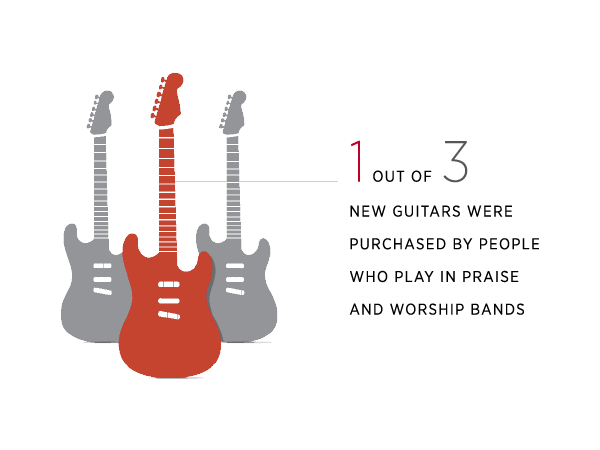

Fender Musical Instruments Corporation sold a record number of guitars in 2020, driven in part by people forced to stay at home during the pandemic. The company calculates that nearly a third of those new musical instruments were purchased by people who play in praise and worship bands.

This may not be surprising to anyone who knows a worship leader.

“Worship leaders are always commenting about wanting to get a new guitar,” said Adam Perez, a postdoctoral fellow in liturgical studies at Duke Divinity School. “There are conversations about needing to ‘up my guitar’ and discussions about types of guitar. For a lot of worship leaders, the guitar is that companion that marks your journey and marks your development as an authentic worship leader.”

No one knows the first person to bring a guitar into church, but it became common in charismatic congregations in Southern California in the 1970s.

Folk, rock, and folk-rock went to church with the hippies who converted during the Jesus People movement, and guitars became staples of the Calvary Chapel and Vineyard church style before spreading to other evangelical churches.

The style signaled openness and authenticity to white baby boomers raised on the Beatles, but guitars also had some practical advantages, according to Perez. They were portable. When a new church started in a school, or someone’s house, or even on the beach, no one had to haul over an organ. Guitars are also easier to learn to play than the pianos and organs traditionally used in church music.

“People joke about how simple it is—three chords or four chords—but that was a strength, not a weakness,” Perez said. “You could have a beginner guitar player who learned to play to lead their small group, their cell group, or even a new church. You’re democratizing access to the sacred.”

Worship music in the 2020s is not all guitar-based, but industry experts know there is a lot of money in church guitars. According to Ultimate Guitar, an estimated one million guitar players are “gigging” at churches every weekend, and more people play praise and worship music than any other genre in the US.