Messengers (delegates) to last summer’s annual meeting of the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) overwhelmingly approved a denominational peace plan. However, ongoing tensions between moderates and conservatives in the 14.6 million-member denomination are becoming increasingly evident.

New conservative majorities on committees and boards are having a dramatic impact on the denominational agencies they govern. Last month, the SBC’S Public Affairs Committee recommended severing 50-year-old ties between the denomination and the Baptist Joint Committee on Public Affairs. And in Wake Forest, North Carolina, a volatile board of trustees meeting at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary resulted in the announced resignations of seminary president W. Randall Lolley and dean of faculty Morris Ashcraft.

Seminary Tensions

Meeting last month for the first time with a conservative majority, the Southeastern Seminary board of trustees vowed that all new faculty members would be biblical inerrantists. Said Robert Crowley, the new board chairman: “We will hire faculty who believe that the Bible is without error. We’re now able to review people under consideration [for faculty appointments]—that’s brand new and our most significant action.”

Following the trustees’ meeting, Lolley announced his intention “to set into motion with the trustees the process of terminating” his presidency. Rod Byard, the seminary’s director of communications, said Lolley believes “his vision and the vision of the majority on the board of trustees are at variance with each other.” Under those circumstances, Byard said, Lolley felt he “could not fulfill his responsibilities as president.” Faculty dean Ashcraft also announced his intention to step down.

SBC-affiliated seminaries have long been a key point in the conservative-moderate debate. Many conservatives charge the institutions with teaching doctrines contrary to Southern Baptist positions on issues such as biblical inerrancy. And Southeastern Seminary is considered by most conservatives to be among the most liberal institutions in the denomination.

Crowley said in an interview that several faculty members and students probably will not be pleased by the seminary’s “shift to inerrancy.” But he added, “In the long run, I see Southeastern Seminary being a great evangelical, evangelistic force on the east coast of the United States.”

The Southeastern faculty, in response to what it sees as a threat to academic freedom, has formed the school’s first chapter of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) and has secured legal counsel. At a news conference following the trustees’ meeting, Southeastern AAUP president Richard Hester said the faculty would not sign the “Baptist Faith and Message” statement if required to do so by the trustees. According to SBC president Adrian Rogers, the 1963 statement upholds Scripture as inerrant in all areas.

“W have already signed the Articles of Faith, which is part of the seminary charter …,” Hester said. “Those are the terms under which we have taught since we came, … and those are the terms that we intend to teach under.”

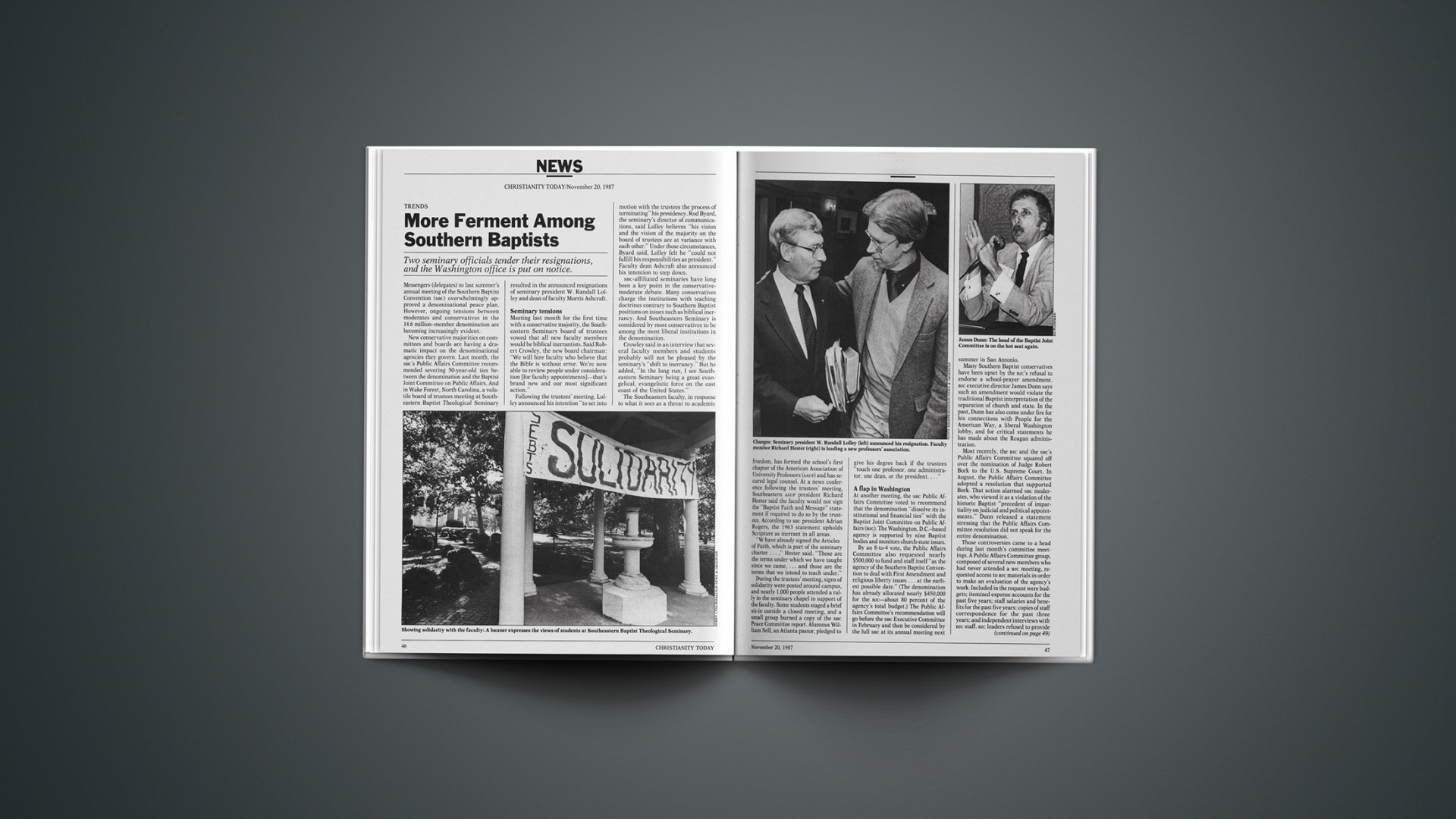

During the trustees’ meeting, signs of solidarity were posted around campus, and nearly 1,000 people attended a rally in the seminary chapel in support of the faculty. Some students staged a brief sit-in outside a closed meeting, and a small group burned a copy of the SBC Peace Committee report. Alumnus William Self, an Atlanta pastor, pledged to give his degree back if the trustees “touch one professor, one administrator, one dean, or the president.…”

A Flap In Washington

At another meeting, the SBC Public Affairs Committee voted to recommend that the denomination “dissolve its institutional and financial ties” with the Baptist Joint Committee on Public Affairs (BJC). The Washington, D.C. based agency is supported by nine Baptist bodies and monitors church-state issues.

By an 8-to-4 vote, the Public Affairs Committee also requested nearly $500,000 to fund and staff itself “as the agency of the Southern Baptist Convention to deal with First Amendment and religious liberty issues … at the earliest possible date.” (The denomination has already allocated nearly $450,000 for the BJC—about 80 percent of the agency’s total budget.) The Public Affairs Committee’s recommendation will go before the SBC Executive Committee in February and then be considered by the full SBC at its annual meeting next summer in San Antonio.

Many Southern Baptist conservatives have been upset by the BJC’S refusal to endorse a school-prayer amendment. BJC executive director James Dunn says such an amendment would violate the traditional Baptist interpretation of the separation of church and state. In the past, Dunn has also come under fire for his connections with People for the American Way, a liberal Washington lobby, and for critical statements he has made about the Reagan administration.

Most recently, the BJC and the SBC’S Public Affairs Committee squared off over the nomination of Judge Robert Bork to the U.S. Supreme Court. In August, the Public Affairs Committee adopted a resolution that supported Bork. That action alarmed SBC moderates, who viewed it as a violation of the historic Baptist “precedent of impartiality on judicial and political appointments.” Dunn released a statement stressing that the Public Affairs Committee resolution did not speak for the entire denomination.

Those controversies came to a head during last month’s committee meetings. A Public Affairs Committee group, composed of several new members who had never attended a BJC meeting, requested access to BJC materials in order to make an evaluation of the agency’s work. Included in the request were budgets; itemized expense accounts for the past five years; staff salaries and benefits for the past five years; copies of staff correspondence for the past three years; and independent interviews with BJC staff. BJC leaders refused to provide several of the requested items, leading to the Public Affairs Committee vote to cut Southern Baptist ties to the agency.

In response, Dunn said the Public Affairs Committee’s “course of action clearly departs [from] the Baptist way” and would “definitely destroy the ‘jointness’ of the Baptist Joint Committee.” He said he did not think approval of the recommendation would destroy the BJC because “there are literally several million Southern Baptists who believe very strongly in the Baptist way as the Joint Committee has enunciated it on religious liberty and church-state separation.” Dunn noted the full SBC has approved continued relations with and support for the BJC on three separate occasions in the past four years.

Moderate leader James Slatton, pastor of River Road Baptist Church in Richmond, Virginia, said the recent tensions are the result of “hard-ball politics” being waged by a “mean fundamentalist machine.… Our task is to awaken our constituency to the fact that they’ve given power into the hands of people who are going to wreck this great denomination.”

Conservative leader Paige Patterson, head of the Criswell Center for Biblical Studies in Dallas, disagreed that the tensions are products of church politics. Rather, he said, they are the natural results of new conservative majorities making “changes that had to come.

“For the last 25 to 35 years, the leadership of the convention has been out of step with the supporting constituency,” he said. “… We had reached the end of the line on paying the salaries of people to teach the opposite of what we believe. It’s like shipping scrap metal to the enemy to get it shot back at you.”

Further Developments

Ongoing friction between moderates and conservatives has led to other developments in the SBC.

- Lee Roberts, a leader among conservative Southern Baptists, sent a 16-page letter to thousands of Georgia Baptists accusing Mercer University of hosting “debauchery” and university officials of having “spiritual convictions contrary to the Baptist doctrine.” Fueling the controversy was the appearance of some Mercer students in a recent issue of Playboy magazine. The Georgia Baptist Convention supplies a small percentage of the university’s budget.

- Earlier this fall, in a 15-to-15 vote, conservatives lost a bid to remove N. Larry Baker as the executive director of the SBC Christian Life Commission. The commission works on social issues for the denomination, and some conservatives have expressed questions about the extent of Baker’s prolife convictions.

- Shelby Baptist Association in Memphis, Tennessee, voted last month to withdraw fellowship from Prescott Memorial Baptist Church because the congregation called a woman as senior pastor. Nancy Hastings Sehested assumed pastoral duties at the Memphis church on November 1.

SBC president Adrian Rogers, pastor of Bellevue Baptist Church in Memphis, voted in favor of the action against Sehested’s church. In 1984 the SBC adopted a resolution against women serving as pastors. However, because of the denomination’s polity, such resolutions are not binding on individual congregations.

By Kim A. Lawton.