These days, Bruno Ponce often has a particular worship song running through his mind.

The song, Tauren Wells’s “Making Room,” is a bold declaration of faith: “We’re making room / For a miracle from you. / All we want is your presence. / Turn this room into heaven.”

Ponce has sung those words many times while leading worship for Lantana Community Church in Bartonville, Texas. But the refrain has become more than just a worship anthem—it’s now a personal prayer. Ponce prays for a miracle that will allow him and his family to stay in the United States and continue his ministry.

They only have until March. After that, current immigration law requires Ponce, in the US on an R-1 nonimmigrant religious worker visa, to go back to his home country of Brazil for a year. It would mean uprooting himself, his wife Anna, and their two American-born daughters from the place they now think of as home.

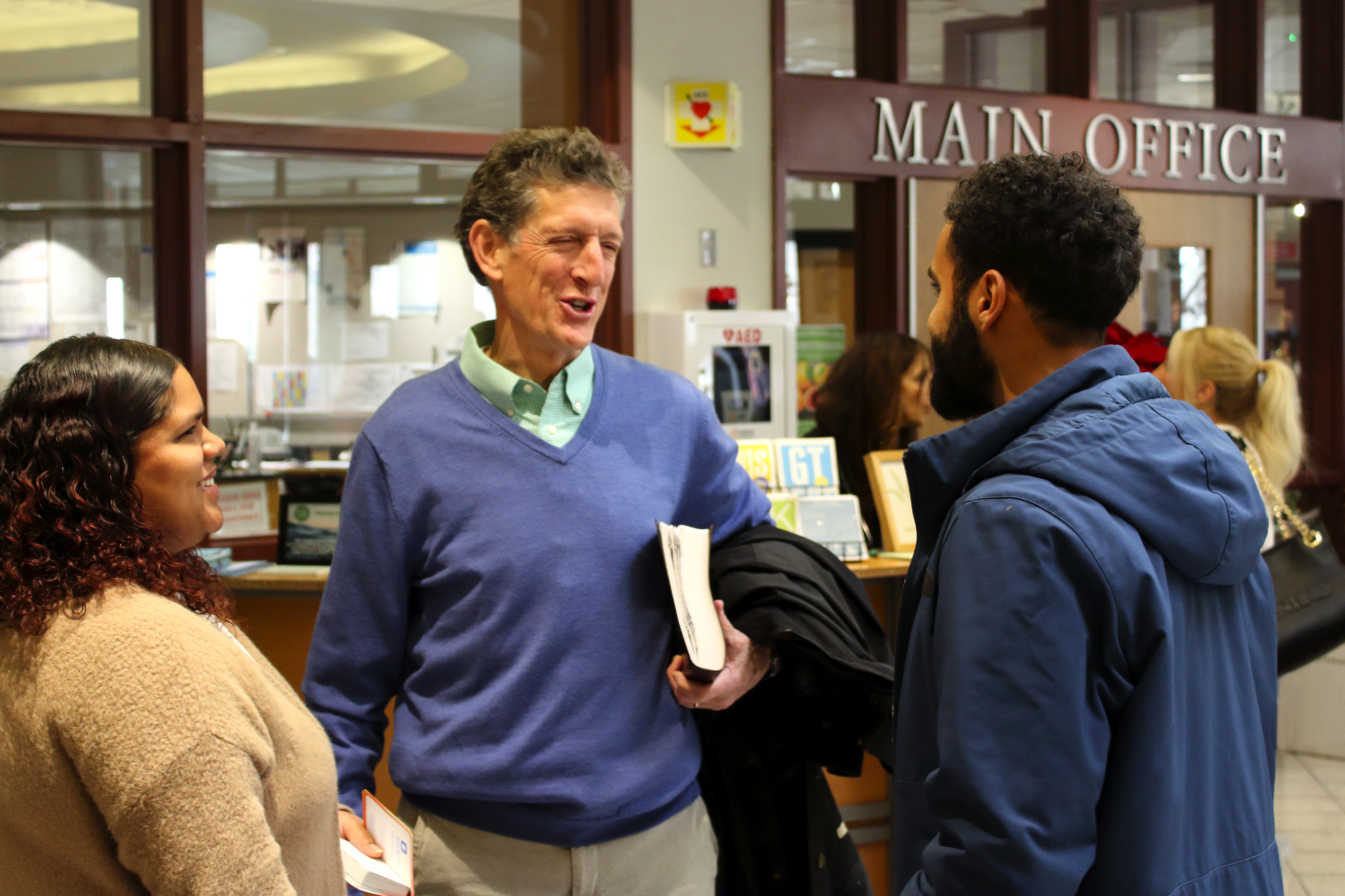

The church is eager to keep the worship pastor. Lead pastor Calvary Callender has hired an immigration attorney and invested time and resources to bring Ponce on staff. He doesn’t want to lose him now. But the US immigration system has proved to be an obstacle course replete with steep costs, shifting requirements, and daunting backlogs.

The same dilemma faces thousands of foreign-born faith leaders, international religious workers, and missionaries from overseas who are in the United States on religious worker visas, as well as the churches, parishes, and ministries they serve.

Religious-worker visa holders may work in the United States for five years. After that, they have to self-deport for at least a year before they begin applying for a new R-1 visa from scratch.

In April, some lawmakers introduced a bipartisan bill that would fix the issue by extending religious workers’ visas until decisions come about their green card applications. The bill would also allow religious workers to make small job or location changes without affecting their green card application process.

It’s a targeted fix that does not change the number of green cards or make it easier for applicants to be approved. Christian advocates say even this small mercy would relieve major disruptions to religious workers’ lives and their communities.

“The access that American churches get to worldwide leadership gifts is something that benefits us,” said Galen Carey of the National Association of Evangelicals, who called this not “an immigration story” and said, “It’s a church story. So even people who are not sure about what to think about immigration questions writ large, this is something they should be able to get behind.”

Religious workers fall under the EB-4 (employment-based, fourth preference) pool. Immigrants apply for green cards, typically through either employment or family connections, on their path to becoming permanent US residents and then eventually citizens. Congress limits the number of green cards annually and the government sorts applicants into different categories. Some categories have much larger backlogs than others.

Religious workers typically work in the United States with sponsorship by congregations or ministries. Until recently, the five-year visa gave religious workers enough time to obtain green cards under the EB-4 category.

The State Department and immigration authorities determine when people can apply for green cards based on assigned priority dates. Each month, that list is updated, and religious workers can check to see if their priority dates are listed.

In March 2023, though, the Biden administration shifted its processing of tens of thousands of applications from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. It placed migrant children who fell under Special Immigrant Juvenile status or who had been neglected or abused into the same employment-based queue as religious workers. Overnight, the pool of applicants expanded dramatically.

Lance Conklin, an immigration lawyer who cochairs the religious workers’ group of the American Immigration Lawyers Association, said the move caused a backlog that will add up to a decade-long wait for religious workers. About 95 percent of Conklin’s clients are evangelicals in this situation.

He works with lots of smaller churches, many with only one senior pastor. Before, many of Conklin’s clients were essentially at the front of the line. Now, “I tell people at least ten years, and it could be longer,” Conklin said. “It’s been pretty devastating. [In a company], take away one of your star employees. What is that going to do to your business? It does the same thing to the church. It hurts.”

Backlogs can shift: The pool may shrink if applicants’ various circumstances force them to give up. Some find other ways to stay, such as through another employment status like H1-B visas, though those can be hard to obtain.

Meanwhile, churches deal with the fallout: “People get attached to their pastor,” Conklin said.

At Lantana Community Church, Callender wonders what he’ll do if Ponce has to self-deport next spring: Hire someone else? Fill the gaps as best he can for a year? Callender said his church followed what officials said in hiring Ponce, “doing everything correctly,” but now “not only are they disrupting his career, but they’re disrupting our church.”

Democratic senator Tim Kaine of Virginia told CT how current immigration policy was affecting his own church, St. Elizabeth Catholic Church in Richmond, along with many others across the United States: “We have had priests who were immigrants, and [we] often have visiting priests, some of whom are immigrants as well.” Republican senators Jim Risch of Idaho and Susan Collins of Maine are cosponsoring the bill. Both the Senate and House versions of the bill are still in committee.

Matthew Soerens of World Relief said that, unlike other immigration issues on the Hill, the bill is not particularly controversial: “Christian denominations and other religious institutions [are] bringing in ministers to meet a very clear need … and doing so in a lawful way, in a way through a program that Congress has set up. I have not found a lot of opposition to that anywhere.”

The bill has garnered bipartisan support, unusual in Washington, but it’s not getting much attention and may never get voted on. It’s not grabbed the spotlight in DC, but it’s crucially important for churches like Iglesia Presbiteriana Corpus Christi, a Spanish-speaking church in Waukesha, a Milwaukee suburb.

Mark Kaiser, chair of the Wisconsin Presbytery Missions Committee, hired a Mexican-born pastor, Luis Garcia, to plant Corpus Christi, but Garcia’s five years will be up next year. Unless the law changes, Garcia, his wife, and his son will have to leave. “If he leaves the country for a year, that church plant will die,” Kaiser said. “It won’t make it.”