Norman Hall knew what he needed to do. The new president of Simpson University was appointed in 2018 to save the Christian and Missionary Alliance-affiliated school in Redding, California. The hard part was how.

Enrollment was dropping at Simpson. In 2014, more than 1,000 full-time undergraduate students signed up to start classes in the fall. Four years later, there were only about 620. With that sharp decline in enrollment, revenues were disappearing fast. Faced with a budget shortfall, the administration eliminated 56 faculty and staff positions—but it wasn’t enough.

With the budget in crisis, the Northern California school was in danger of losing its accreditation. The Western Association of Schools and Colleges notified Simpson it was on a two-year probation. Things needed to turn around, quick, so the school hired a new president and presented Hall with this problem.

From his perspective, there were really only two options. Cut the budget. And attract more students. It wouldn’t be easy.

“It’s like you have a living organism,” said Hall, who studied biology and sociology before earning his doctorate in educational administration at Pepperdine University. “You’re going to reduce some of the tissue in one area and grow tissue in another area and you don’t want to kill the organism.”

Many of Simpson’s peers—small evangelical colleges and universities across the United States—are making similar calculations about where to cut and what to grow. Declining enrollments have thrown evangelical higher education into crisis. Administrators, experts, and many close observers believe that Christian colleges will have to change to survive. What no one knows, right now, is whether any of the changes they’re making will be enough.

The critical issue for small evangelical schools is the number of students paying tuition. Most small colleges’ donor base is limited, making it difficult to rely on fundraising or the endowments that buoy big state schools and Ivy League institutions. For the evangelical Christian schools that are full members of the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities (CCCU), tuition accounts for about 80 percent of revenue, said Tim Fuller, an enrollment consultant.

“For most of these campuses, they rise and fall on enrollment,” said Fuller, who works with the North American Coalition for Christian Admissions Professionals (NACCAP).

Evangelical schools have been concerned about enrollment for a long time. But then the financial crisis of 2008 created serious problems. Responding to their economic uncertainty, prospective students and their parents seemed to increasingly prioritize an education that would lead to a good job over one that would integrate faith and learning.

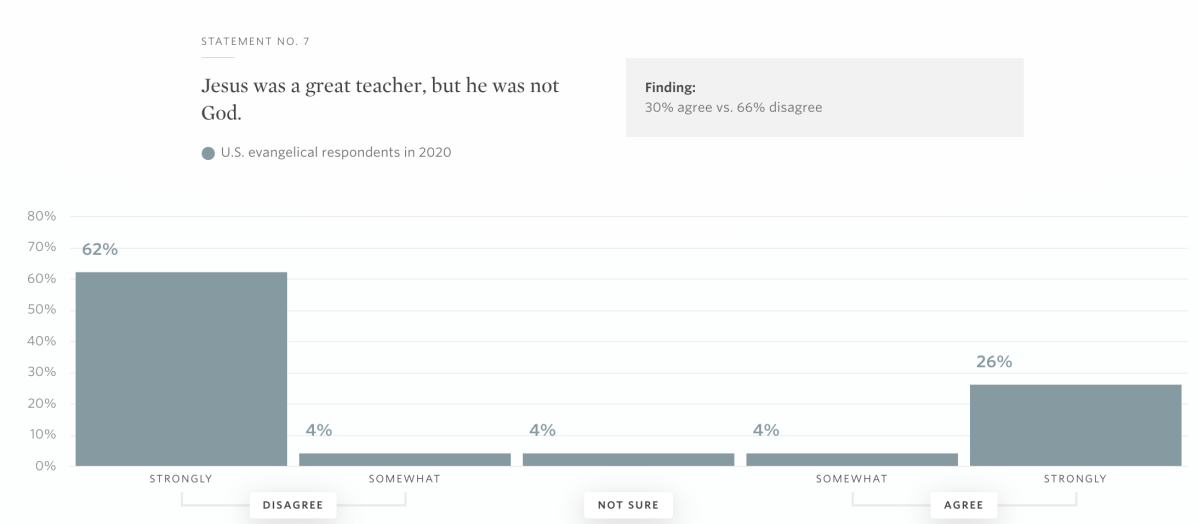

Add to that the declining birthrates, which lead to fewer people attending college, the shrinking percentage of young people who identify as evangelical Christians, and concerns about rising rates of college debt. Small, private Christian colleges were hit with a crisis.

New Programs: Engineering and Fishing

Sixty five percent of the CCCU-affiliated schools saw full-time undergraduate enrollment drop between 2014 and 2018, according to data from Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS). There was a loss of more than 3,000 students for the 112 US schools that are full members of the CCCU.

In response, evangelical institutions started adding new programs to attract new students. Adding a major can make a Christian college competitive with a nearby state school, so about 65 percent of CCCU institutions have added programs since 2010. According to CT’s survey, the most popular new majors at evangelical colleges include nursing, engineering, computer science, and other technology related fields. The schools have added more than 126 new undergraduate programs, according to news reports and press releases, as well as about 50 athletic programs, including esports, bass fishing, fly fishing, acrobatic tumbling, swimming, and football.

Simpson added three new programs: engineering, computer information systems, and digital media. The school also added several sports programs, including swimming and bass fishing.

There is a limit to how much this helps, though. For one thing, it isn’t cheap to launch a new program, according to Gillian Stewart-Wells, provost at Judson University in Elgin, Illinois. Judson has sought to enroll more graduate students so it’s less reliant on undergraduate enrollment. However, costs associated with masters or doctorate programs, including library books and adjunct salaries, are higher than undergraduate programs.

“We need to be very strategic about making sure that it doesn’t tip the scales,” Stewart-Wells said.

Adding programs doesn’t upset a campus in the same way that cutting programs invariably does, but it also doesn’t always solve the problem. According to Fuller, a new program may attract students initially, but there can be a challenge with keeping those students over the next few years.

Debating Essential Identities

If adding programs doesn’t work, the other option is subtraction. Since 2010, CCCU schools have cut at least 84 undergraduate majors, as well as 11 minors and 19 graduate programs, according to news reports and press releases. A few majors were merged into other departments or became minors. The most common eliminations at Christian colleges came from the language departments, humanities, education, and ministry. Many students at Christian colleges can no longer major in worship ministry, philosophy, or French.

There’s no centralized database keeping track of faculty cuts and the elimination of staff positions, but a CT survey shows that at least 944 jobs have been eliminated at CCCU schools in the last decade. About 30 percent of the evangelical schools have let people go.

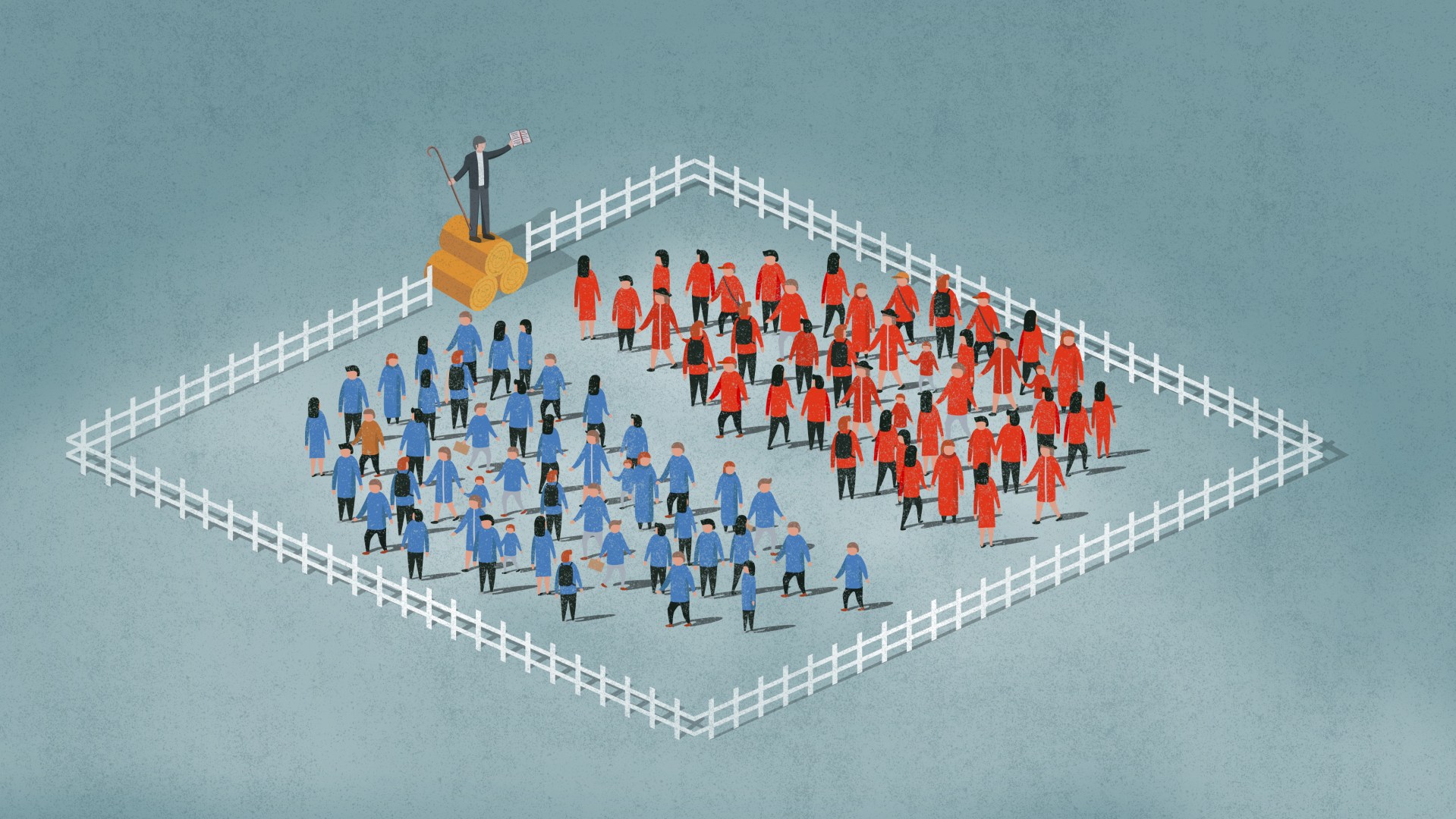

Cuts can be deeply divisive to Christian college communities, pitting people against each other in heated debates about what is essential to the school’s mission and identity. Humanities faculty and college administrators, in particular, become locked in conflict. Faculty sometimes say they feel the administrators don’t appreciate the value of the liberal arts; the administrators say the faculty don’t understand the dire financial realities forcing tough decisions.

“No one’s happy about this. No one’s happy about cuts. No one’s happy about people losing their jobs and programs being cut,” said John Fea, a history professor at Messiah University.

If the financial problem creates a crisis, for many schools the solution creates one too. Some CCCU institutions have worked hard to show ongoing support for the humanities, even as they make cuts.

At Bethel University in Minnesota, historian Chris Gehrz said administrators showed him they supported liberal arts education, even as they merged the history department with political science and philosophy.

“If my position was affected, I would surely resent it and I would surely be complaining about what’s happening to history at Bethel,” Gehrz said. It was clear, though, that tough decisions had to be made. Bethel is cutting a total of 36 faculty positions, along with 28 staff, two masters programs and 11 majors. The history department lost a faculty member.

The best practice is for schools to be deliberate about stating priorities, and acknowledge that adding some programs and cutting others is a re-prioritization, said Greg Christy, president of Northwestern College in Iowa.

Full-time undergraduate enrollment dropped about 13 percent at Northwestern between 2014 and 2018, according to IPEDS. A sizable endowment gave the Reformed Church in America school some support, but the administrators were nonetheless alarmed by the declining number of new students.

“We couldn’t just continue to do business as usual. We needed to make some changes for the long-term flourishing of the institution,” Christy said.

The school launched a budget prioritization committee made up of faculty and administers. They developed a five-category rubric, and then used it to determine where they could trim the budget. The committee gave its report in May 2019. In December, the school eliminated the literature, philosophy, and writing departments, and cut 11 faculty positions.

Since then, Northwestern has added a master’s program training physicians’ assistants. Christy said it had its largest new class, counting 1,075 undergraduate and 461 graduate students, enrolled this fall.

“We are in a position where we can actually take some calculated risks,” Christy said.

According to Fuller, budget re-prioritization is probably overdue for most CCCU schools.

“I see this as, in many ways, institutions making healthy choices to do things that they maybe should have done have couple years ago,” he said. “But now they don’t have any choice, they have to do it.”

The delay may not be the worst thing, according to Fuller. It’s important for schools to take time when making these decisions and really evaluate the programs they’re considering cutting or adding. Sometimes they will add a new program and that will cost money, but not attract enough new students. Other times they’ll cut a program that didn’t seem to drive enrollments, only to find out too late that it was critical to retention.

Crisis in the Christian Humanities

The stakes are higher than that, though, according to Joe Creech, director of the Lilly Fellows Program at Valparaiso University, which includes a network of about 100 church-related colleges and universities. As schools make changes to survive, they may lose the very thing that made them special.

“An institution that cuts its humanities or liberal arts can certainly be a good Christian flight school or truck driving school and be deeply Christian,” Creech said, “but it’s not doing liberal arts education.”

The humanities are integral to the identity of many CCCU institutions. Christian liberal arts exist to give students a different set of intellectual tools—not just to prepare them for a job, but to open up deep questions of the soul.

“The tools of theology, the tools of Christian worship are the tools of the humanities,” Creech said.

To many students, though, and to many colleges, humanities programs may seem like a luxury they cannot afford. Simpson decided it would have to cut Spanish and its undergraduate program for theology and ministry. If students are especially interested in the subject, they can choose a five-year theology program that will give them graduate credits.

Many CCCU school administrators are feeling a moment of reprieve right now because COVID-19 hasn’t had the immediate negative impact on enrollment that many feared.

Early reports suggested that 2020 enrollment deposits at CCCU schools who are part of NACCAP are at about 97 percent of 2019 rates, Fuller said, based on an analysis of NACCAP data.

The Demographic Cliff

The long-term prognosis still looks pretty grim, though. In a few short years, schools are facing what some experts are calling “the demographic cliff.” America’s low birthrates declined with the economic crisis in 2008 and haven’t gone up again since. This means than in 2025 or 2026, there will be fewer college-bound students. The effects will likely vary by region and institution, but experts predict that most schools can expect to see a 10 to 15 percent drop in enrollments.

For small Christian institutions, that will be hard to survive. Schools like Simpson say they are doing what they can be ready and taking things one step at a time.

At least for now, the cuts and subtractions at Simpson seem to have worked. Enrollment is up. The school successfully renewed its accreditation. Hall is feeling encouraged. But everyone knows the university’s future isn’t certain, he said.

“One day, in the midst of our doing everything we can in a Christ-centered context, if there is no longer a need for Simpson,” he said. “We’ll figure that’s God’s gig.”