J. I. Packer was my teacher at Regent College when I was a young graduate student. Some years later, he became my colleague and next-door neighbor in the hallways at the college and a fellow church member at St. John’s Anglican Church in Vancouver. I will forever be grateful to have known him. He shaped my life and thought in many ways, and I am not alone in this experience.

In light of his recent passing, I have been thinking more about his wider legacy and especially his significant contribution to evangelicalism as a whole. In the present political culture, however, the word “evangelical” or “evangelicalism” is freighted with a good deal of baggage that’s worth shedding immediately.

We can do so by going back in time. The Old English word “gospel” never got a proper Old English adjective and had to steal a Greek one: “evangelical.” But the noun and the adjective belong together. And as the great Bible translator William Tyndale put it, “evangelical” is a word that “signifieth good, merry, glad and joyful tidings, that maketh a man’s heart glad, and maketh him sing, dance, and leap for joy.”

This vibrant relationship between word and life, message and experience, doctrine and devotion was absolutely central to the evangelical movements in Germany and English-speaking lands that emerged at the beginning of the modern period.

Evangelicals today claim some sort of genealogical or theological continuity with these movements. But wherever we see the preaching of Jesus Christ generate new life and set people in joyful motion, that is where we properly use the adjective “evangelical” in its most important and basic sense. It is why we cannot, I think, abandon the term. Again, the words “gospel” and “evangelical” ought always to be kept together. Indeed, Jim Packer played a significant role in evangelicalism over the past six decades precisely because he helped those who identify as social evangelicals to be theological and spiritual evangelicals as well.

With this context in mind, I can think of six roles that sum up Packer’s contribution to the modern evangelical movement.

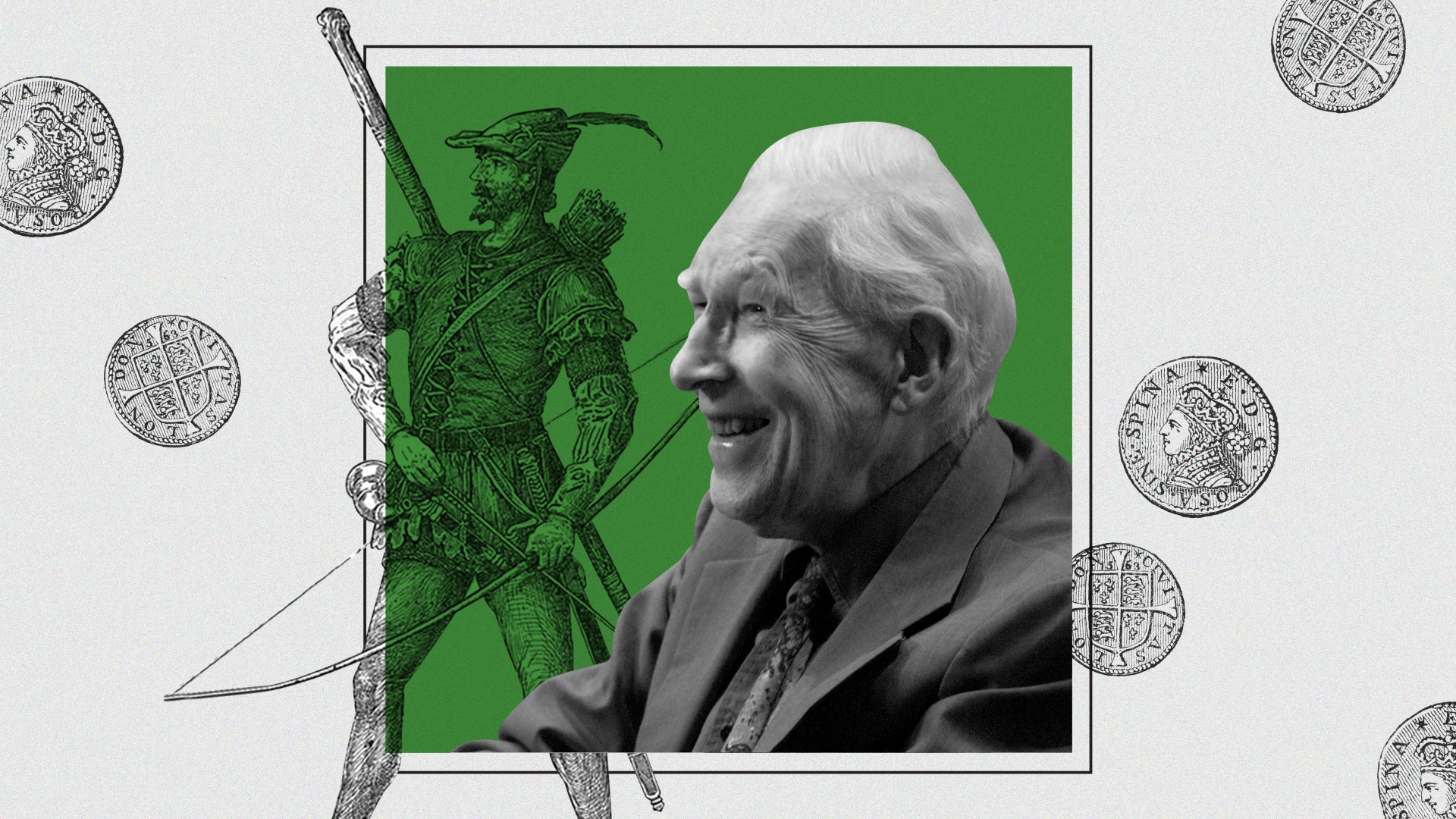

First, he was the Robin Hood of evangelicalism, stealing from the rich and giving to the poor.

By training and by dint of his own disciplined study, Packer acquired early in his career a deep knowledge of church history and the classic works of Christian theology. Popular evangelicalism, on the other hand, has often been profoundly ahistorical and anti-intellectual in its outlook. Just as the absence of good King Richard left England in turmoil during the time of Robin Hood, so modernity has caused troubles for the church.

Illustration courtesy of Phil Long

Illustration courtesy of Phil LongNot to put too fine a point on it, but Packer described North American Protestantism as “man-centred, manipulative, success oriented, self-indulgent, and sentimental.” He therefore contrived, like Robin Hood, to “take from the rich and give to the poor.” He was able to retrieve riches from the past and employ them for the purpose of renewing the life of Christians in the present.

In his essay, “On from Orr,” Packer wrote, “As an Anglican, a Protestant, an evangelical, and … a ‘small-c’ catholic, I theologize out of what I see as the authentic biblical and creedal mainstream of Christian identity, the confessional and liturgical ‘great tradition.’” From these riches, he addressed the poverty of popular evangelicalism, which he once described as “3,000 miles wide and half an inch deep.” We are all richer on account of his theological generosity.

Although he “stole” from the whole wealth of church history and the great tradition, he came early to the conviction that the Puritan tradition, in particular, contributed much to the church today. Indeed, he was one of the key catalysts in the post-war revival of Puritan or neo-Calvinist theology among evangelicals on both sides of the Atlantic.

Second, Packer was what Time once called the “theological traffic cop of evangelicalism.”

Throughout its history, evangelicalism has been a movement, with all the fluidity that that word implies. Without a magisterium or a visible church order or hierarchy, it has not always been clear how theology functions to regulate evangelical belief and practice or to unite evangelicals around core doctrines. In this context, amid all the diversity and denominational pluralism of 20th-century evangelicalism, Packer was, according to Time, a “doctrinal Solomon.”

“Mediating debates on everything from a particular Bible translation to the acceptability of free-flowing Pentecostal spirituality,” wrote the magazine, “Packer helps unify a community that could easily fall victim to its internal tensions.”

Illustrations courtesy of Phil Long

Illustrations courtesy of Phil LongThrough the influence of Knowing God, Packer emerged as a theological arbiter among evangelicals. In the West, as well as in Singapore, Hong Kong, Korea, and other countries where his works have been translated and loved, many evangelicals have looked to Packer’s writings as the embodiment of evangelical theology. Packer was an international traffic cop, too.

In his regulatory role, Packer was willing to engage in controversy and contend for the faith. Any number of issues within evangelical ranks drew his fire, but he was especially concerned with the threat of theological liberalism to the faith of ordinary Christians. As he often said, liberal Christianity has no grandchildren. Wherever Packer saw revisionist liberal traffic approaching, he held up a hand, blew his whistle, and refused to let it merge onto the evangelical roadway.

In addition to being a Robin Hood and a theological traffic cop, Packer was also a plumber.

In the winter of 1989, on the occasion of his installation as the first Sangwoo Youtong Chee Professor of Theology at Regent College, Packer gave an inaugural address titled “An Introduction to Systematic Spirituality.”

He called for a marriage of sorts: “I want our systematic theology to be practiced as an element in our spirituality,” he said, “and I want our spirituality to be viewed as an implicate and expression of our systematic theology.” Evangelical theology and evangelical life were to be inseparable.

Illustrations courtesy of Phil Long

Illustrations courtesy of Phil LongAt the close of his address, though, Packer donned his plumber’s bib and brace, as it were, and described his role alongside Jim Houston, who had been teaching spiritual theology at Regent for more than a decade. “Strengthening every way I can the links between spirituality and systematic theology will certainly be high on my agenda,” Packer said. “I do not think l shall cramp Dr. Houston’s style. What I do will be more in the nature of digging out foundations and putting in drains, leaving the air clear for him to fly in, as at present.”

The role of “Packer the plumber” at Regent College might be extended more broadly to his work within evangelicalism at large. In the context of a growing interest in spirituality by the wider postmodern culture, Packer played a role as Plumber in Chief, keeping the drains clear and digging out the foundations with the aim that all may soar aloft in healthy, unpolluted air.

Packer was also fundamentally a catechist.

Illustrations courtesy of Phil Long

Illustrations courtesy of Phil LongFrom his post at Regent, and with the popularity of Knowing God, Packer effectively became a catechist-at-large for evangelicals. This was his “sweet spot” as a communicator. He was a scholar through and through, as bookish and tweedy as they come, yet he spoke and wrote not for specialists in peer-reviewed publications but for general audiences. To be sure, he was never short on content—“Packer by name, Packer by nature,” he said—but he wrote to be understood.

While some academics might have wished that Jim had written more for specialists, this was not his sense of personal mission. He was a catechist first. Given the social structure and character of evangelicalism as a popular movement, it will always need those who can communicate in exactly this register. And Jim did this better than anyone.

From my perch in Vancouver, I was privileged to witness some of the ways that Packer lived out his catechist vocation in our local church. For decades, he was the inspiration behind a thriving adult Sunday school class that still goes by the humble name “Learner’s Exchange.” Although Jim regularly contributed, the course was lay led and lay taught most weeks. He sat there utterly in his element and positively beaming while adult Christians, serious about their faith, learned together Sunday after Sunday.

Fifth, Packer was a bridge-builder among evangelicals.

My wife and I live on the south arm of the mighty Fraser River on the delta where it empties into the Pacific Ocean. Some years ago, our provincial government employed an army of engineers to plan a new bridge to span the river and connect us better to the rest of Vancouver.

We might picture Packer as one of those highly skilled bridge-building engineers who knew exactly how and where to connect distinct communities. He was Reformed, he was Anglican, and he was evangelical. Yet in his writing, teaching, debating, and worshipping, he looked for common ground with charismatics, Roman Catholics, and Orthodox believers.

Illustrations courtesy of Phil Long

Illustrations courtesy of Phil LongPacker’s approach was not to pursue some sort of abstract via media agenda but rather to unite Christians around biblical teaching and a thoughtful consideration of church history. He described evangelicalism as an “ethos of convertedness within a larger ethos of catholicity.”

Convertedness is a divine dynamic, generated by an understanding of the gospel and issuing forth in a renewal of life. It’s like a mainstream current within the great Mississippi River, a mainstream that flows onward, despite eddies and bayous, mudflats, and reed beds. Creeds and councils mark the banks of the river. Faith, repentance, fellowship, communion, holiness, and service are all the while being renewed by the coursing life of the Spirit. Given this spiritual ethos, Packer was eager to make common cause with faithful believers in other Christian communions.

The last role I would assign to Jim Packer is, well, that of Tigger from A. A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh stories.

In The House at Pooh Corner, where the character is first introduced, Tigger says of himself, “Bouncing is what Tiggers do best.” Piglet agreed: “He just is bouncy … and he can’t help it.” For many years, this is the picture I have had of Jim Packer coming into the building at Regent College with a spring in his step—boing, boing, boing—as if he were walking on springs. Being more temperamentally an Eeyore by nature, I have looked on in wonder and admired his effervescent Christian joy.

Illustrations courtesy of Phil Long

Illustrations courtesy of Phil LongJim had a zest for life, a real whimsical streak, and a genuine cheerfulness. He also had a remarkable, dry wit, a love of clarinet and classic jazz music, a love of steam trains, a love of literature, and a love of food. His Asian friends like to see him keep up with them, spoonful for spoonful, with the hottest curries and spicy meals.

By the grace of God, he sustained this joyful spirit even in the midst of suffering and real disability. His personal witness to the joy of being a Christian and a theologian was itself a significant contribution to evangelicalism.

This brings us full circle to Tyndale’s idea that the word evangelical “signifieth good, merry, glad and joyful tidings, that maketh a man’s heart glad, and maketh him sing, dance, and leap for joy.” Like Tigger.

Indeed, in his old age, Packer knew that there was still a joy set before him. As his beloved Richard Baxter wrote in Saints’ Everlasting Rest, “We are on our way home, and home will be glorious.” Packer knew well that the wise man will “live, as it were, packed up and ready to go.”

Friends, Packer was packed. Here, at the end, in his joyful expectation of heaven, he was doing what he had always done: keeping evangelicals connected with the gospel.

Bruce Hindmarsh is the James M. Houston Professor of Spiritual Theology and professor of the history of Christianity at Regent College, as well as the author of The Spirit of Early Evangelicalism: True Religion in a Modern World.

This essay was adapted from a talk titled “The Significance of J. I. Packer for Evangelicalism,” given at the 2016 annual meeting of the Evangelical Theological Society on the occasion of Packer’s 90th birthday.