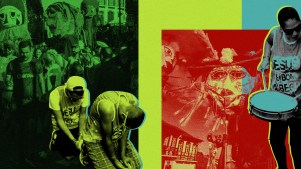

Latino evangelicals in the US are reaching the unchurched and drawing in converts despite funding shortfalls, widespread community fear, and other challenges caused by the federal government’s immigration crackdown.

Lifeway Research said in a new study—which surveyed leaders at 292 new Hispanic church plants, campus sites, and other ministries—that the average new Hispanic congregation almost tripled in size (from 31 to 85) within eight years of its founding and saw 10 conversions its first year before reaching 15 per year down the line.

Most protestant churches in the US reached fewer new people in the past year. It’s common for church plants to focus more on outreach as they aim to grow and embed themselves in their communities. But new Hispanic congregations have been “particularly evangelistic in their approach” and have continued to be that way as their congregations mature, said Scott McConnell, executive director of Lifeway Research.

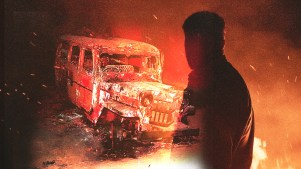

At the same time, the study—funded by Exponential, eight denominations, Biola University, and Wheaton College —showed burgeoning Hispanic churches are grappling with President Donald Trump’s aggressive deportation campaign.

Half of the leaders surveyed said they “have had to address pain and fear” in their congregation caused by government practices in the past year. About a third (35%) said attendance declined because undocumented members were afraid to leave their homes. Meanwhile, a similar amount (34%) noted church finances have taken a hit because undocumented members have not been able to work.

Latino leaders who were not included in the study have also witnessed significant declines in church attendance this year. Undocumented congregants worry they can be picked up anywhere, including in church, where detention and other immigration enforcement is now possible. Some worship leaders were detained and other ministry leaders have been deported.

One pastor who leads a 400-member congregation in Maryland told Gabriel Salguero, president of the National Latino Evangelical Coalition, that only 40 people are showing up regularly for Sunday service at his church. The rest are watching online.

“The group that is part of the … revitalization of the church is the one who’s now feeling under siege,” said Salguero, also the pastor of The Gathering Place, an Assemblies of God church in Orlando.

Leaders surveyed by Lifeway also noted more members have needed “tangible help” in the last year. More than a quarter said members have been discouraged by a disrespectful cultural tone toward Hispanics. Separately, 38% reported they’re seeing greater interest among unchurched Hispanics who are looking for hope.

Nearly two-thirds of Hispanic Protestants supported Trump during last year’s presidential election. Voters were driven by economic dissatisfaction and resonated with the president’s approach to other cultural issues, such as sexuality, abortion, and parental rights. Recent polling, however, shows a majority of Latinos in the country—including Protestants—disapprove of the president’s performance in the White House, with immigration emerging as a key concern.

“Many who voted for the president have said, ‘We did not vote for this; we support the deportation of violent criminals, but this is not what we asked for,’” Salguero said.

Some findings from the Lifeway report mirrored a similar study published by the research firm six years ago. Most lead pastors of new Hispanic churches (77%) are still first-generation immigrants, as are nearly two-thirds of their flock. The majority of congregants (56%) in these ministries had either never attended church, didn’t go for many years, or were migrating from Catholic churches. Nearly half (46%) of the congregations surveyed are Southern Baptists and approximately half are located in the South, where the Latino population has grown. About a fifth (21%—the next highest percentage) are affiliated with the Assemblies of God.

A lot of Hispanic churches are already multiethnic, drawing congregants from Mexican, Puerto Rican, and other Latino backgrounds. Most of the leaders surveyed say their ministries have sought to reach all Hispanic people, but a portion (29%) note they are also aiming to reach other ethnic groups.

New congregations hold outreach Bible studies and keep up with door-to-door evangelism after the launch of their ministries, though slightly fewer do so compared to the previous survey. A majority also put together “fun social events” and service projects to reach new people. Most hold their services in Spanish, while some offer bilingual services or separate services in different languages.

Samuel Rodriguez, pastor of New Season Church in Sacramento and the president of the National Hispanic Christian Leadership, said “it is inevitable” for Hispanic congregations to diversify by the second and third generations. By then, Rodriguez said, kids tend to lose touch with the Spanish vernacular, which eventually leads churches to launch an English service. Over time, the English service can become larger than the Spanish service, he said, drawing in different audiences.

The missional mindset has always been prominent in Hispanic evangelical churches. Growing up, Alvin Padilla, a professor of New Testament at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, said the Sunday evening services he saw were often evangelistic in nature. Saturday mornings would also be devoted to visiting individuals or families, and pastors would routinely encourage congregants to bring friends to church. This study bears that the sense of urgency to reach new people has remained, he said.

Church planters surveyed said it’s important for partners to understand cultural differences in Hispanic communities, prioritize relationships over programs, and offer better financial support. Most pastors and leaders launching ministries are bivocational and have worked another full-time job to sustain their families. Some (29%) did not receive any financial compensation from their churches in the first five years, while others have used their work salary for church needs.

In addition to practical help, leaders say more collaboration with established churches, networks, and patience in the church-planting process would help them and their ministries.

The entire Lifeway report can be found here.