Peace will come only when three levels of conflict are resolved.

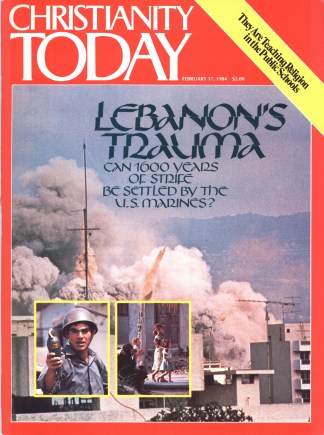

The lebanon puzzle is like three-dimensional tic-tac-toe. The first level is the religious/ethnic maze: Shi’ite Muslim versus Sunni Muslim versus Maronite Christian versus Eastern Orthodox versus Druze. The second level is the regional conflict: the Arab-Israeli rivalry and the unresolved Palestinian issue. The third level is the international confrontation between superpowers.

Independent only since the end of World War II, Lebanon has failed at the first level in making its citizens nation-conscious. They think of themselves first as members of smaller communities, and only secondarily as Lebanese.

The issue is also confused because these communities are identified by their religious labels (Christian, Sunni or Shi’ite Muslim, Druze, and so on). It would therefore be easy to assume that a religious war is under way, with freedom of worship at stake. This is not the case. The Metropolitan of the Greek Orthodox church in Lebanon has correctly observed that “Christians are not killed because they confess Christ.” Evangelicals witnessing to the various communities of Lebanon have encountered more hostility in the past from Maronite and Orthodox elements than they have from Muslims.

When the various communities in Lebanon are identified by their religious affiliations, these labels should be understood sociologically more than theologically.

To break the impasse at this first level of conflict, three steps must be taken:

1. Redistribute power in a manner seen to be fair by the underrepresented Muslim communities. The government led by the minority Christian communities does not like to face up to genuine discontent among the Muslim majority, although it first surfaced some 30 years ago. Instead, it looks for excuses to explain away the increasingly violent protest.

2. Provide safeguards for the minority Christian communities. Some have recommended the abolition of political sectarianism. Such sweeping reform is now not a practical possibility since the Christian communities would perceive it as an attempt by the Muslim communities to dominate. This would increase their historical fear of being swallowed up in a Muslim-Arab world.

Significantly, representatives of the major communities were coaxed into meeting in Geneva last November, and they agreed to major changes in Lebanon’s 40-year-old National Covenant, which had awarded the Christian communities political power over the Muslim communities. Thus, the theoretical groundwork for reconciling the Lebanese communities is largely in place.

3. Create a central government more assertive than the current laissez-faire system. The Lebanese government has ensured freedom unmatched in the Arab world. But there have been few checks on those freedoms, making it more of a playground—social and financial at first, now military—than a nation. Even before 1975, many major politicians maintained their own well-armed militia as bodyguards or enforcement services, unstopped by the government so long as they did not stray too far into official terrain. There are now 17 major militias as well as dozens of smaller groups.

It was the second level of conflict, regional tension, that started the pot boiling again. This was stimulated particularly by the 1980 invasion of Lebanon by Israelis, their brutal seige of West Beirut, and their introduction of Maronite community militia into areas that have been Druze for generations. Predictably, the Israeli arch rivals in the region jumped in too. In seeking to pull Israel’s chestnuts out of the fire, the U.S., French, Italian, and British forces have suffered heavy casualties.

There are some ironic results of this whole episode: The militia of the Maronite community, long subsidized by the Israelis, is now in a weaker position relative to those of the Druzes and Shi’ites. And Syria has completed what Israel was unable to do, driving the PLO from Lebanese territory.

The third level of conflict, between superpowers, was recently addressed by former Undersecretary of State George W. Ball. In a column addressed to President Reagan, he charged: “You are misinterpreting local Middle Eastern conflicts to fit your anti-Soviet rhetoric. You try to blame Syria for all the complex problems of Lebanon and talk as though Syria were a mere puppet of Moscow, which is manifestly not the case.” Ball’s blunt assessment is on target because Syria has a mind of its own. But the Soviets do provide massive aid, and this means influence. Unquestionably, foreign elements, particularly Syria, have played an important role in the conflict. But they would have found no opportunity to enter the fray had the Lebanese communities not been fighting each other already.

We can think of no easy answers. Internally, the conflict between the various ethnic groups must be addressed. Regionally, the Arab-Israeli rivalry and the Palestinian question cry for solution. Internationally, the confrontation between the superpowers must be defused.

Lasting peace will come to Lebanon only if conflict at all three levels is resolved.