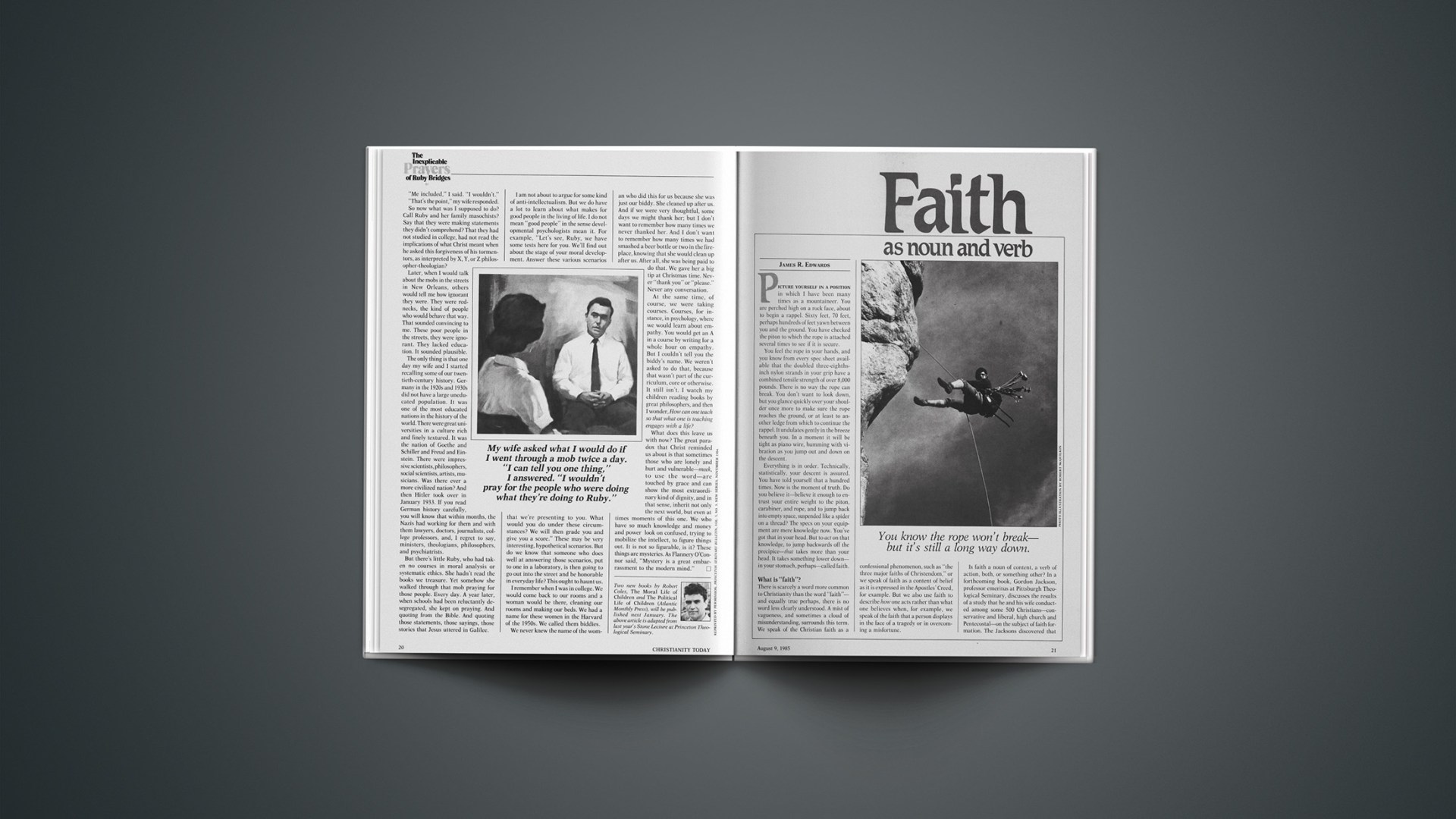

You know the rope won’t break—but it’s still a long way down.

Picture yourself in a position in which I have been many times as a mountaineer. You are perched high on a rock face, about to begin a rappel. Sixty feet, 70 feet, perhaps hundreds of feet yawn between you and the ground. You have checked the piton to which the rope is attached several times to see if it is secure.

You feel the rope in your hands, and you know from every spec sheet available that the doubled three-eighths-inch nylon strands in your grip have a combined tensile strength of over 8,000 pounds. There is no way the rope can break. You don’t want to look down, but you glance quickly over your shoulder once more to make sure the rope reaches the ground, or at least to another ledge from which to continue the rappel. It undulates gently in the breeze beneath you. In a moment it will be tight as piano wire, humming with vibration as you jump out and down on the descent.

Everything is in order. Technically, statistically, your descent is assured. You have told yourself that a hundred times. Now is the moment of truth. Do you believe it—believe it enough to entrust your entire weight to the piton, carabiner, and rope, and to jump back into empty space, suspended like a spider on a thread? The specs on your equipment are mere knowledge now. You’ve got that in your head. But to act on that knowledge, to jump backwards off the precipice—that takes more than your head. It takes something lower down—in your stomach, perhaps—called faith.

What Is “Faith”?

There is scarcely a word more common to Christianity than the word “faith”—and equally true perhaps, there is no word less clearly understood. A mist of vagueness, and sometimes a cloud of misunderstanding, surrounds this term. We speak of the Christian faith as a confessional phenomenon, such as “the three major faiths of Christendom,” or we speak of faith as a content of belief as it is expressed in the Apostles’ Creed, for example. But we also use faith to describe how one acts rather than what one believes when, for example, we speak of the faith that a person displays in the face of a tragedy or in overcoming a misfortune.

Is faith a noun of content, a verb of action, both, or something other? In a forthcoming book, Gordon Jackson, professor emeritus at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, discusses the results of a study that he and his wife conducted among some 500 Christians—conservative and liberal, high church and Pentecostal—on the subject of faith formation. The Jacksons discovered that Christians of varying persuasions characteristically understand “faith” in three ways: as trust, belief, and commitment. Each of these terms is clearly witnessed to in Scripture, and together they offer a helpful understanding of what the Bible means by faith.

Faith Is Trust

The first thing that must be said of faith from a biblical perspective is that it is trust in the person of Jesus Christ. In the Gospels and Epistles of John, for example, the Greek word for “believing” occurs 98 times, and in every instance except one (1 John 5:4) it is a verb! That means that for John, faith is an active trust in Jesus Christ before it is a content of belief. The same could be said for the other New Testament authors, for whom the gospel of salvation is not so much a formula but a person, Jesus Christ, in whom God encounters us.

Not infrequently in contemporary Christianity we see a shift in emphasis from the person of Jesus Christ to formulations about him. Faith thereby becomes an intellectual assent to a propositional statement. Most of us can see rather quickly, however, that assent to a propositional statement, such as “I believe there are nine planets that orbit the sun,” can be utterly removed from the way we live. In similar fashion, the proposition “Jesus is the Son of God,” itself a true statement, does not insure that the one who says it is a Christian. The Bible itself warns against conceiving of faith as mere intellectual assent to a proposition. James 2:19 says, “You believe that God is one; you do well. Even the demons believe—and shudder.” The Devil, of course, believes in the existence of God and knows well who Jesus Christ is, but he is scarcely to be counted among the redeemed. Sloganeering is not saving faith.

God became a human being in Jesus of Nazareth not merely to change our models of thought or patterns of speech, but to change who we are and the way we live. The change or conversion that God wills for us is possible only through trust in his Son. When we recognize that faith is trust we confess that it is personal. This means that we do not put trust in things, but rather in persons, and for Christianity, in the person of Jesus Christ.

Things, such as machines, operate according to predictable laws. Anyone who puts water into the gas tank of his car and trusts that the car will run is not acting in faith; he is simply violating the laws of an internal combustion engine. Persons, however, do not operate according to predictable laws, and consequently, if they are to be known they must be trusted. Trust means believing that a person will do so-and-so even though he is free to do otherwise. Trust is risk, not proof. But there are some things in life—indeed the most important things—that we cannot know apart from such a risk. If someone says, “I love you,” you or I cannot experience that love apart from trusting the one who said it. If one tries to “prove” it, he will kill it. A man who hires a private detective to spy on his wife to determine whether or not she is faithful to him while he is away on a trip will, of course, only destroy whatever love his wife may have had for him.

So it is with faith in Christ. If we rigidly insist on “certainty” (however it might be demonstrated), we are only admitting that we desire a thing to be proven rather than a person to be known. A similar rigidity in human relationships would prevent the formation of a single friendship, much less a life-long contract such as marriage.

When my daughter was a small girl she loved the story of Peter Pan. On family outings she would hurl herself from high places, pretending that my outstretched arms were Peter Pan rescuing her after walking the plank of Captain Hook’s pirate ship. But when my daughter grew older, she began to notice the distance to the ground. Her knowledge of the world began to challenge her trust in me.

“Are you sure you can catch me?” she would plead. Her plea was in actuality the dilemma that confronts anyone who desires to trust God: was she willing to trust in Daddy’s arms despite the distance to the ground? In a similar fashion, whoever desires to experience salvation must trust, despite moods and prevailing circumstances, in the credibility of the one who offers it, Jesus Christ.

Faith Is Belief

A second characteristic of biblical faith is that of belief. Belief is not the same as the act of trusting. Belief refers to the “what-ness” of faith rather than the “who-ness.” It means that there is some content “out there,” apart from us, in which to believe. It is true and real even if we do not recognize it, or choose not to believe it.

We sometimes hear it said that faith is believing something we know is not true. Believing something you know is not true is, of course, to reduce the object of belief into a mere sentiment of wishful thinking. If faith is a sentiment to which we commit ourselves despite our better judgment, then we dare not disturb it with hard evidence. Faith, then, becomes simply another popular myth, like “talent-plus-hard-work equals success,” or “good guys win in the end.” We all, of course, know talented people who have never “made it” (and probably some not-so-talented who have); and who of us would dare to foist the “good guys” bit on a Vietnam veteran of yesterday or a small farmer today? If faith is purely a sentiment, then it bears but faint relationship to reality, and a believer can hold it only at the expense of intellectual suicide.

A related misconception is that faith is something for which we possess no evidence, or at best only a low degree of evidence. Faith, it is assumed, is but an arbitrary choice on the part of the believer, somewhat like believing in UFOs. Some may choose to believe in them, others not; but either way is fairly safe since (for the present, at least) there is no evidence either to confirm or refute their existence. Belief then becomes simply what one wants to believe, an arbitrary choice, a flip-of-a-coin mentality.

Both of these misconceptions fail, either through misinformation or ignorance, to recognize the historical reliability of the Scriptures. On a purely historical-critical level, there is no document in all of ancient literature that can claim the overwhelming manuscript support, both in early dating and number of copies, that the New Testament possesses. To my knowledge, there is no book in human history that has been subjected to more rigorous and sustained investigation than has the Bible, while continuing to maintain its integrity.

The Bible is the record of the God who reveals himself in Jesus Christ. Whoever reveals something about himself limits the possible range of opinions that others might hold of him, for to reveal something is no longer to be anything. This is also true of God. The Bible testifies, for example, that God draws near to humanity rather than remaining passive and aloof; that God desires to love sinners rather than to condemn them; and above all, that the death of Jesus Christ on the cross is adequate atonement for the sins of anyone who will receive him. Throughout the history of the church, creedal formulations have attempted to define those aspects of the nature and work of God that are necessary for salvation, and to avoid errors that would endanger it.

All this has to do with “belief.” If some things about the God who has revealed himself are true, and other things false, then knowing the difference between them is important if we are to know God and receive his benefits. Jesus confessed himself to be “the way, the truth, and the life” (John 14:6). If we value who he is, then we will also value the truth about him. Hence, one aspect of Christian faith, in the words of Jacques Ellul, is that we pledge our minds to that Truth.

Our world, however, is in rebellion against the God who makes himself known in Jesus Christ. One consequence of that rebellion is that the world seeks in various ways to change the truth of the gospel. George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four dramatizes this reality in one especially graphic scene. The rebel Winston Smith is captured and subjected to torture. He is lectured by his tormentor, O’Brien: “You believe that reality is something objective, external, existing in its own right.… But I tell you, Winston, that reality is not external. Reality exists in the human mind, and nowhere else. Not in the individual mind, which can make mistakes, and in any case soon perishes; only in the mind of the Party, which is collective and immortal. Whatever the party holds to be truth is truth.”

O’Brien then holds up four fingers. “How many fingers am I holding up, Winston?”

“Four,” replies Smith.

O’Brien turns a dial on the wall, which blasts an electrical current into Smith. “How many fingers, Winston?”

“Four,” gasps Smith.

O’Brien turns the dial further. Smith writhes uncontrollably. “How many fingers, Smith?”

“Four! Four! What else can I say? Four!” screams Smith desperately.

The dial is advanced to maximum voltage. Smith will do anything, say anything to escape the pain.

“How many fingers am I holding up, Winston?” asks O’Brien.

“I don’t know,” bellows Smith. “I don’t know. Four, five, six—in all honesty I don’t know.”

“Better,” says O’Brien at last. Smith is beginning to “learn.”

Orwell’s message, of course, is that the party determines how many fingers O’Brien is holding up. There is no “objective” number. If the party says there are five, or two, or thirteen—then that is how many there are.

Orwell’s story of O’Brien and Smith illustrates something that the Judeo-Christian tradition has known from the beginning: The world is forever trying to make reality, humanity, and even God in its own image. That is why Christian faith, if it is true to the revelation that it receives through the Holy Spirit and Scripture, must always confess that faith is a content of belief in addition to an act of trust.

Faith Is Commitment

Finally, biblical faith is commitment. Commitment is that act of the human will that dedicates one’s life—all that one is, all that one has, all that one will ever be—to the one, true God who became a person in Jesus Christ. Commitment is the opposite of a faddish or fair-weather faith, which seizes now one opportunity and then another, a mere sampling of trends and “in” things. Commitment is guided by a sense of ultimacy and is willing to forgo the short term for the long run. It is that act of faith that leads to obedience, as Paul says repeatedly in Romans 6. Commitment, in short, means living in the present according to God’s promises for the future.

In the fall of 1940 during World War II, the German air force, in an average of 200 planes per raid, bombed the city of London for 57 consecutive nights. On numerous occasions the then prime minister, Winston Churchill, could be seen picking his way through smoke and rubble, decked out in suit and derby, and with his ubiquitous cigar, encouraging his countrymen. In the end, of course, England not only survived, but, in alliance with the United States, went on to defeat Germany in 1945. Following VE Day, Churchill was asked what he had done during the interminable nights of the bombing of London. He responded that he had retired to his bomb shelter below Piccadilly Square and there, with a desk lamp illuminating a map of Europe, he planned the invasion of Germany.

That is commitment: Making plans for victory even while one’s enemy builds siege works from below and rains terror from above. The commitment of faith is the same. Despite the state of affairs, despite the way we may feel, despite current trends and forecasts, despite threats or even signs of defeat, we believe that God is true and faithful and that “nothing in all creation can separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Rom. 8:39). God’s will and God’s way will prevail. To believe that means to act as if it were everywhere and always true, for indeed, someday, by God’s grace and sovereignty, it shall be.