With the start of a new year, a slightly more liberal Congress convened on Capitol Hill. Later this month, after his inauguration, Ronald Reagan will embark on a second term as President.

Observers will be watching closely to see whether November’s election proved that Republicans have a lock on the White House, or merely that a popular Republican temporarily holds the key. There is evidence to support both views.

Republicans have won four of the last five presidential elections, with a cumulative lead of 44 million votes. They carried 169 states to the Democrats’ 21 in those elections, receiving 82.4 percent of the electoral votes. The Republican party’s vision of America appealed to more women, young voters, immigrants, and working-class people last year than anyone dreamed possible.

Reagan won more popular votes than any other President—more than 53 million—and a record 525 electoral votes. (The President who came closest to this achievement was Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who won 523 electoral votes in 1936, when there were 48 states.) However, Republican victories in Congress fell short of the party’s hopes, failing to place Reagan firmly in the driver’s seat. Meanwhile, a throng of contenders for the 1988 presidential nomination already is taking shape, casting the Republican party’s future onto the unsettling variables of ideology, personality, and political maneuvering.

The make-up of the Ninety-ninth Congress notwithstanding, the President is entitled to assume a personal mandate from the 1984 election results. And in light of transcendent values in American society, his landslide victory represents more than the personal triumph of a popular President. In several congressional races, prolife candidates defeated prochoice opponents. Only one antiabortionist senator was defeated, and radical feminist candidates were overwhelmingly rejected.

The Coattail Factor

While it is true that the Reagan landslide did not produce the congressional gains Republicans anticipated, it would be wrong to conclude that his reelection was merely the victory of a “great communicator.” The history of second-term Republican Presidents, as well as developments in last year’s campaign, help explain the absence of a major coattail factor.

The victories of previous Republican incumbents show remarkable similarities to last year’s election. In 1956, Dwight D. Eisenhower won 57.5 percent of the vote and 457 electoral votes. But the Republican party that year lost two seats in the House and stayed even in the Senate. In 1972, Richard Nixon swept 60.5 percent of the popular vote and 520 electoral votes, but Republicans gained only 12 House seats and lost two in the Senate. Reagan’s victory was strikingly similar: Republicans gained 14 seats in the House and lost two in the Senate.

The President’s poor showing in his first debate with Walter Mondale contributed to his failure to swing Congress his way. Had he won, his strategists would likely have sent him across the country stumping for Republican House and Senate candidates. Instead, he spent the two weeks between debates focusing on his own campaign. Some candidates, anxious for a presidential endorsement in person, charged that the Reagan-Bush ’84 campaign leaders were indifferent about congressional races.

Ultimately, Reagan’s campaign themes were most responsible for the divergence between the presidential and congressional election results. Feeling good about America, characterizing the nation as standing tall again or voters seeing themselves as better off than four years ago all added up to keeping the President in power for another term. At the same time, that message did not lend itself to “throwing the rascals out,” and thus shaking up the congressional lineup. Significant shifts are most likely to come when the public sees a candidate or party as “the enemy.” That was the case in 1964 when Lyndon Johnson portrayed Republicans as apt to propel the nation into nuclear war.

In the recent election, the Democrats’ gain of two seats in the Senate left Reagan’s party with a 53-to-47 seat margin, identical to that of 1981 when he began his first term. But apart from party identification, the Senate is ideologically more liberal than it was in 1981. Its newly elected leaders, including majority leader Robert Dole, share a streak of independence that may place Senate Republicans at odds with the administration on certain issues.

Senate Races

Several evangelicals retained their Senate seats. Mark O. Hatfield (R-Oreg.) overcame allegations last summer of impropriety and swamped his opponent by carrying every county in Oregon for a career-high 66 percent victory. His lifelong reputation for integrity served as a reservoir of good will among voters.

William Armstrong (R-Colo.) won a second term against Lt. Gov. Nancy Dick. Well-known for his Christian commitment, Armstrong was the primary Senate sponsor of the Year of the Bible in 1983. His opponent accused Armstrong of trying to shove his values down peoples’ throats. Armstrong achieved a 64 percent win, with Dick compiling a lower percentage of the vote than any Democratic Senate candidate in Colorado history.

In North Carolina, Republican incumbent Jesse Helms scored a 52-to-48 percent victory over Gov. James Hunt. Massive registration and voter turnout efforts among evangelical and fundamentalist churches aided Helms’s victory.

Though the North Carolina race was the most expensive, the nation’s political action committees donated much more money to the U.S. Senate contest in Illinois. The challenger, Democratic U.S. Rep. Paul Simon, unseated incumbent Sen. Charles Percy by 50 to 49 percent. Simon is a lay leader in a Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod congregation and the brother of Bread for the World President Arthur Simon.

Iowa voters continued an 18-year tradition of not rewarding a senator with a second term. Republican incumbent Roger Jepsen lost to former U.S. Rep. Thomas Harkin by 56 to 44 percent. It was revealed during the campaign that in 1977 Jepsen applied for membership in a health spa that offered nude modeling and rap sessions with nude women. He faced the issue squarely, acknowledging that he had applied for membership before his conversion to Christianity. The liberal Des Moines Register editorialized that no one should question the validity of Jepsen’s conversion, and that the health spa incident should not be an issue.

However, on the weekend before the election, Harkin supporters delivered copies of Jepsen’s health-spa application to Protestant churches. In addition, flyers were sent to Catholic churches, stating, “Roger Jepsen believes that if your daughter … is raped and has an abortion, she should be put to death for the crime of murder.”

Throughout his campaign, Jepsen rejected some important offers of help from the religious New Right. He declined voter registration efforts and other campaign assistance, although he had been closely associated with religious conservatives throughout his Senate career. Late in the campaign he telephoned Moral Majority leader Jerry Falwell, asking him not to come to Iowa. In short, he carried whatever liabilities may be attached to the religious New Right without gaining substantially from its benefits.

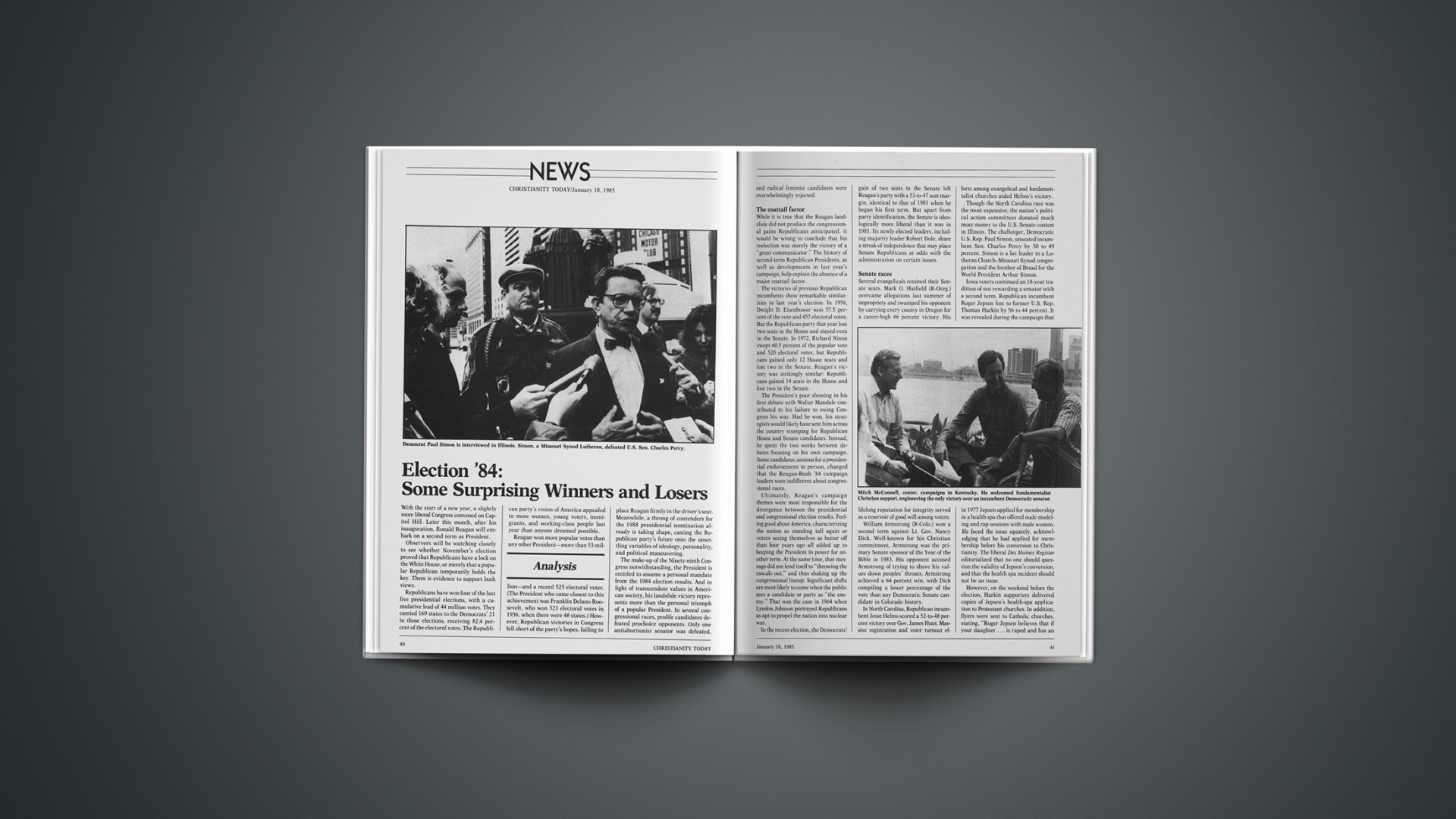

In contrast, Kentucky Republican Mitch McConnell welcomed fundamentalist Christian support, with Falwell taping radio commercials for him. McConnell defeated U.S. Sen. Walter Huddleston by the narrowest of margins, engineering the only victory over an incumbent Democratic senator. However, at least three evangelical challengers failed to unseat Senate incumbents, including former U.S. Reps. Albert Lee Smith (R-Ala.) and Ed Bethune (R-Ark.), and astronaut Jack Lousma, a Michigan Republican.

House Contests

Many Americans mistakenly believe the presidential race was a popularity contest while the congressional races were ideological. The reverse is usually true, and proved especially so in 1984. The televised debates let voters know where Reagan and Mondale parted company on issues. Moreover, the party platforms have seldom been so polarized. When it comes to Congress, however, most voters are abysmally ignorant of the voting record of their representative. In House races, name recognition and the specific ways incumbents have helped their constituents count most. These factors added up to victory for 95 percent of House incumbents who sought reelection.

Among evangelical Democrats winning reelection were Don Bonker (Wash.), Tony Hall (Ohio), Marvin Leath (Texas), and Bill Nelson (Fla.). Among Republicans, evangelicals who are returning for another term include Dan Coats (Ind.), Mickey Edwards (Okla.), Jack Kemp (N.Y.), Bob McEwen (Ohio), and Carlos Moorhead (Calif.).

One noteworthy newcomer to the House of Representatives is Paul Henry (R-Mich.), a former state senator and political science professor at Calvin College. Henry won handily in Gerald Ford’s old district. The son of former CHRISTIANITY TODAY editor Carl F. H. Henry, he gained national notice when political commentator David Broder lauded him in a column last September.

Former U.S. Rep. Robert Dornan, a California Republican, lost his House seat by running for the U.S. Senate in 1982. Seizing an opportunity last year, he moved into California’s thirty-eighth district and ousted Democrat Jerry Patterson. John Paul Stark, a former Campus Crusade for Christ staff administrator, failed in his third attempt to unseat Democrat George Brown in the thirty-sixth district. The Religious Right supported both Stark and Dornan.

Stark faced a specialized attack because of his formal identification with a Christian organization. In a direct mail piece, George McGovern alleged that Stark would be “Jerry Falwell’s favorite Congressman.” Stark speculates that his upbeat campaign might have succeeded if it had taken a more negative turn at times, with an aggressive attack against his opponent’s positions. Stark received strong support from evangelicals, and noted that their involvement has increased significantly since the outset of his first campaign. Yet he said evangelicals in general are less politically dedicated than, for example, antinuclear activists or environmentalists.

Religion And Politics

In state contests as well as national races, candidates parried with the notion that religion and politics do not mix. In 1980 and 1982, prolife activists and evangelicals were rebuffed by Minnesota’s Independent Republican party. They were brushed off as overzealous amateurs and scorned as single-issue activists. In a reversal of the proverbial phrase, these committed people apparently decided, “If you can’t join ’em, lick ’em.” Flooding last year’s party caucuses, they virtually took over the state’s Republican party (CT, Sept. 21, 1984, p. 68). As a result, 14 out of 17 new Republicans in the Minnesota House of Representatives, many of them evangelicals, are opposed to abortion. U.S. Sen. Rudy Boschwitz (R-Minn.), who is Jewish, applauded the entry of so many Christians into the party. With his prolife commitment, Boschwitz handily won a second term in the senate.

Nationally, religious issues appeared to play directly into Reagan’s reelection. Polls indicated that the President was in trouble after the Democratic convention in July. Mondale and his party initially did a good job of co-opting family, flag, and values themes stressed by Reagan. But for more than a month following the Republican convention in August, religion and politics continued to dominate the presidential race.

It appeared that the bottom dropped out of Mondale’s campaign when he began arguing that religious values do not belong in the political arena. The Mondale-Ferraro attacks on certain religious leaders backfired because millions of Americans felt their own beliefs were under attack. Christians were offended at the implication that they should separate their biblically based values from their pursuits as citizens.

Television network exit polls generally showed that “born-again Christians” supported the President’s reelection by at least 10 percent more than his 59-to-41 percent national margin. The New York Times/CBS News poll showed that 81 percent of “white born-again Protestants” voted for the Reagan-Bush ticket.

The same poll indicated that the abortion issue was far more influential among evangelicals than among other groups. “Every radical proabortion feminist woman who ran for the Senate was defeated,” said National Right to Life Committee president Jack Willke. “Prolife Senate incumbents, who only a few months ago were judged as threatened, all came back with the sole exception of Senator Jepsen in Iowa.” Pro-life activists provided the critical margin in Democrat Marilyn Lloyd’s fight to retain her House seat against a pro-choice Republican challenger in Tennessee.

Nothing kept abortion on the front pages more effectively than the running feud between vice-presidential nominee Geraldine Ferraro and Catholic church officials. For whatever reason, Ferraro could not produce what the National Organization for Women promised: a gender-gap vote for the Democratic ticket. As it turned out, 54 percent of women voters supported Reagan. The real gender gap ambushed Mondale, with 62 percent of male voters supporting the President. Nonetheless, Ferraro was a pioneer, and all women can be gratified that a door heretofore closed has been opened to them.

A Word Of Caution

A few days after the election, pollster Lance Tarrance observed that, in the political realm, evangelicals are “here to stay.” In his opinion, they have moved “beyond emerging and are now mobilizing.” As that process occurs, evangelicals begin bumping up against obstacles. The Republican party has welcomed evangelical involvement. But when Christians begin to move into the power structure, they sometimes are seen as a threat. Such a response isn’t always an anti-Christian reaction, but the natural dynamic that can operate when people holding power begin to find it diluted.

Evangelicals occasionally attract controversy by approaching politics with an arrogant attitude, believing they have all the answers and the right to “take over” their political party apparatus. That happened in Oregon in 1978 when a fundamentalist pastor became Republican party chairman. No candidate could run for office with party endorsement unless he or she passed the chairman’s personal muster.

Anything Christians do should be done according to bibilcal principles. In politics, that means the primary motivation must be to serve. When that is the case, and evangelicals prove faithful and effective, they rise to leadership very quickly.

Ultimately, Christians must concern themselves with efforts to transform society through the spiritual processes of evangelism and equipping believers for ministry. Political engagement is a secondary, but equally valid, process of trying to reform society through education and election. The church’s task, as Carl Henry puts it, is to announce the criteria by which a holy God is going to judge nations as well as individuals and to try to help change the thinking of the country. Christians need to share those criteria with their fellow citizens—eventually prompting change to come from the bottom up, from shifting public sentiment. Meanwhile, direct political involvement is at an all-time high.

Evangelicals have helped elect a President they overwhelmingly favored. Yet presidential leadership alone would not have provided the Equal Access Act, a law that enables high school students to use public school facilities for religious purposes. In addition, presidential leadership alone has not provided any means of curtailing abortion.

This much is certain: The Reagan administration provides a favorable climate that should motivate evangelicals, both Democrats and Republicans, to increase their involvement in local party structures. Further, they should continue influencing decision makers on Capitol Hill. With increased involvement, Christians can help assure that people of competence, character, and godly values will continue to rise into positions of national leadership.

1 An ordained Conservative Baptist minister, Dugan is director of the National Association of Evangelicals’ office of public affairs in Washington, D.C. In 1976, he ran for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. He writes a monthly newsletter, NAE Washington Insight.