If only my draft board could see me now.

Here I am on a Thai Airways flight from Bangkok to Hanoi: 30 years after France gave up on Vietnam, 20 years after we decided to bomb Hanoi, 15 years after our final withdrawal from Saigon. I am traveling with a former marine captain, Bob Seiple, who flew 300 combat missions over Vietnam. As president of World Vision, a Christian relief-and-development agency, he now spends much of his time figuring out ways to finagle humanitarian aid (medical supplies, resins for artificial limbs, and visas for G.I.-fathered orphans) into a country our government doesn’t officially recognize.

A warrior turned peacemaker, Bob Seiple is still sorting out his feelings about Vietnam. So am I.

So, apparently, are the American people. University classes on the war are filled to capacity. Moviegoers flock to see what our nation’s pop psychologists, Hollywood filmmakers, have to say. My local Crown Books store has 104 history titles on display, 32 of which are on Vietnam. America is still searching for a resolution to a war that won’t go away.

What kind of bandages can bind the psychological wounds left from 58,000 dead Americans, 600,000 dead South Vietnamese, and over 1,000,000 dead North Vietnamese?

Hanoi: A Familiar Flight

For Bob Seiple, this flight into Hanoi over war-worn northern Vietnam is a familiar one. Most of his bombing missions were here. “I was a soldier doing my duty,” he says, “so it’s not a question of guilt. But I feel a great sadness for the people of this country who have suffered, and still suffer, so much.”

My feelings aren’t of guilt either. I don’t ever remember feeling guilty about missing a war my friends so faithfully fought. But I do remember feeling confused. And I still do. I read Dispatches, a heart-tearing, in-the-trenches Vietnam War journal by Michael Herr, and decide all war is wrong. I read Neil Sheehan’s A Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam and am convinced our government mishandled the war. I read Stanley Karnow’s Vietnam: A History and come away amazed that anyone has ever been able to get along with the stubborn Vietnamese leadership. And when I read about Vietnam’s post-1975 wars with Cambodia and China in Nayan Chanda’s Brother Enemy, I agonize with the Vietnamese people who have been fighting unrelenting war for 40 years.

As we descend into Hanoi’s airport for my first steps on Vietnamese soil, I realize that this ambiguity and confusion carry over to my feelings about how we should respond to Vietnam’s political and economic needs today.

The 40-minute drive from the airport provides my first glimpse of these needs. Sixty-seven million people live in a country roughly the size of California, and at any one time it seems as if sixty-five million of them are whizzing by our van on bicycles.

Most Vietnamese are poor farmers. Seventy percent of the people live in rural areas minding water buffalo, growing rice and other crops. The average Vietnamese can expect to make $150 per year.

But in the environs of Hanoi, small cafés, tire shops, drugstores, and woodworking factories line the roads. It is an unseemly display of private enterprise in a Marxist country. Entrepreneurs have made the best of remnants of the war: parachutes shield open-air cafés from the sun; pieces of temporary metal runways serve as walls for small homes; army jeeps and supply trucks are now delivery vans and private cars. “Fish ponds,” water-filled bomb craters 50 feet wide, dot the landscape, daily reminders of the B-52 barrage we sent Hanoi’s way in the early 1970s.

Despite the rampant signs of individual enterprise, I can never completely forget that this is a communist country. An official “minder” met our flight at the airport and will be ever-present during our stay. Congenial, friendly, helpful, even wise—but always there.

And whenever we meet with official Vietnam, we are aware that we are walking a tightrope. After all, we were at war with these people. Two of our party served in the United States armed forces. It is likely some of the Vietnamese officials did likewise—on the other side. The U.S. government continues to impose trade sanctions against Vietnam. Hanoi politicians still blast the U.S. in speeches.

On a personal level, this tightrope is fairly easily navigated. In private meetings, official arrogance and bravado is replaced by a genuine warmth for the American people. “We miss you,” one man says. “Please come back soon.”

Far trickier is the religio-political tightrope. Theoretically, the Vietnamese constitution allows freedom of religion. In practice, churches, especially healthy, growing churches, are harassed. Church meetings must be okayed in advance. Public evangelism is forbidden. Building permits for churches are not forthcoming. Pastors may not travel outside their parishes. Sermons are constantly monitored.

Sometimes the harassment escalates to persecution. Before flying to Vietnam, I met with a former Vietnamese pastor now living in Los Angeles. Nguyen Cuong was arrested in 1983, held 50 months before trial, and then in 1987 he was convicted and sentenced to eight years in prison. His crime? “They said I violated the order and security of the state,” says Nguyen. The real reason, many say, is that his church grew from 100 to 1,000.

Vietnam is governed by an antireligious system, make no mistake. As representatives of a Christian agency, my traveling companions have to balance carefully several competing objectives: First, offer the humanitarian aid our government licenses us to give; second, be up-front about our Christian motivations for giving that aid; third, offer aid and witness without arousing the Vietnamese government’s religious paranoia or, worse, compromising Vietnamese pastors.

But all that runs far below the tabletop talk of an official dinner like the one we have with Ministry of Health officials our first night in Hanoi. We discuss ways World Vision can help: support for an acupuncture hospital, medicine for an eye clinic, medical journals for a university faculty. We are on a tightrope, we all know, but even as we fight for balance we smile and do our business.

Our meal ends with Asian abruptness—immediately after the last course is eaten we all rise together and leave. But we feel—or hope—that the conversations are one more small, positive step toward new understandings.

The next morning, on our drive to the airport, we take time to stop at the wreckage of a B-52 shot down in 1972. The tail section of the bomber juts out of a watercress pool, surrounded by simple houses in the heart of Hanoi. A woman in a black-pitch boat tends the watercress. Nearby, children spin toy wooden tops, and black-pajamaed girls wash clothes at a spigot.

As we stand contemplating the rusted wreck, an old man walks up. He saw the plane, a fireball from the sky, fall here on May 22 at 10:20 P.M., 18 years ago. Nobody died at the crash site. Only one house burned. We ask the old man if he harbors any grudges against the pilot—or Americans.

“The war was nonsense,” he says. “People are the victims—Vietnamese and American.”

As we drive to the airport for the next leg of our trip, Bob Seiple muses on the conversation. “If the people could vote on war, there’d never be any,” he says. I cannot help thinking that the people of both Vietnam and the U.S. seem ahead of our governments, if the agenda is reconciliation.

Da Nang: The Moral Economics Of Relief

An FAA official riding on Hàng Không, the national Vietnamese Airlines, would have a heart attack. Often the door closes and taxiing begins (on an airstrip dotted with water buffalo and kids) before everyone is seated. Did I say seated? Sometimes there are more people than seats. What are the aisles for, after all?

But by the standard customer measures of success, Hàng Không works: it is reasonably on time, the pilots are good, and the safety record of the Soviet TU-134s is acceptable. Thus we arrive in Da Nang on schedule and circle Monkey Mountain and Marble Mountain to land on a runway that 20 years ago touched down more United States airplanes than most American commercial airports.

The atmosphere of Da Nang still reflects two decades of G.I.-oriented commerce. Where Hanoi is reserved and cool, Da Nang is open and relaxed. The ancient capital, Hue, is just to the north. This area was the embarkation point of early French traders and missionaries who first exposed the Vietnamese to Western ways.

Humanitarian agencies such as World Vision, World Relief, and the Mennonite Central Committee are the only “missionaries” allowed in Vietnam now. Others were forced to leave after the U.S. involvement ended in 1975. It is left to the World Visions of the world to do what they can. We visit two projects they have initiated: a pig-raising farm and a pharmaceutical factory. Both impress us with their efficiency.

Giving money to Christian humanitarian causes might seem like a surer road to reconciliation than the political minefield of Hanoi-Washington politics. Certainly the economic need is unambiguous. And poverty always leads to a second unambiguous problem: disease. Malaria, diarrhea, tetanus, and fever, all treatable diseases, are the greatest killers of today’s Vietnamese.

The needs are clear and the resources available, yet it’s not quite that simple. Relief-and-development agencies struggle with two problems, one moral, the other practical: how to raise money and how to give it away.

One would think that the problems of raising money would stay back home in the United States. Wrong. We visit a rehabilitation hospital in Da Nang. The minute we enter the old 12-bed ward, every eye turns to a 12-year-old girl, recovering from an appendectomy. Her black-suited mother sits on her bed with a bamboo fan, shooing away flies, heat, and the depression of long, empty hospital hours. Our attention is automatically drawn to this particular bed because the girl is pretty, her disease is photographable, and we are accompanied by a film crew making a fund-raising film.

It doesn’t take too many visits before one becomes expert at identifying the “photogenic illness.” To his credit, Bob Seiple is careful to greet every patient in the ward. But still, choices are made. Some of the illness we see is too plain ugly to play on American television.

It is more than just physically ugly—it is morally ugly. The missing limbs and eyes more often than not were blown away by Vietnamese, Cambodian, Chinese, and American bombs, land mines, grenades, and rifles. And the untreated treatable diseases are a direct reflection of a communist system unable to deliver medical supplies. To tell and show the real story would (1) turn off American viewers; (2) alienate the Vietnamese (and probably the American) government; and (3) ultimately render the agencies ineligible to help at all.

The hard moral choices of raising money lead to a second, more practical problem: how to give it away. There are three basic choices: let the indigenous church do it, build your own staff structures to administer the funds, or work through the Vietnamese government.

Our natural inclination might be the church. But in Vietnam, this would very likely compromise pastors. Money brings power, and the Vietnamese government has no intention of allowing the Christian church any power except that which can be used to support government policy.

The second choice is for relief agencies to build their own delivery systems. But in Vietnam, this is impossible. Visas are simply unavailable. Paul Jones, World Vision’s Vietnam field representative, must live in Bangkok and commute to Hanoi. Under trying circumstances, he is remarkably efficient and effective. He could be more so if he lived in the country and could hire staff.

So, left with the third option of working through the government, agencies do what they can. It means there are far more protocol dinners and meetings with government officials than any sane person could possibly enjoy. It means catering to interdepartmental jealousies within the Vietnamese government.

One commonly told horror story is of an agency that raised a million dollars in Europe for humanitarian relief. After it got changed into Vietnam’s currency at the official exchange rate, after goods were bought within Vietnam by government officials (which means a high surcharge for graft and payola), and after allowances were made for the shoddy quality of goods purchased, the $1 million bought about $20,000 worth of humanitarian relief.

Careful, experienced agencies can do much to avoid such scenarios. But the time—and, yes, let’s be frank—that compromises require is significant.

The economic reconciliation bought by these machinations, of course, is valuable. Indeed, we repeatedly witnessed the power of such projects to bring people together. Perhaps the most dramatic had nothing to do with a Western relief agency.

We visited a stiflingly hot rattan “factory.” In a room no larger than most Americans’ living rooms, 12 Vietnamese took raw materials through six production stations, the final a weaving loom that produced baskets, chairs, and mats. All the workers were blind.

In a smaller, even hotter room upstairs, we asked the two old men who ran the factory how they happened to start it. The first had been a soldier in the South Vietnamese army. He removed his sunglasses and showed us two empty sockets—his eyes had been destroyed by a bomb in 1968. The second man had been a North Vietnamese guerrilla. In that same year he had haunted the South Vietnamese mountains, launching many bombs of the same kind that had destroyed the other man’s eyes. He himself lost his eyes (and a hand) when he stepped on a land mine during a raid.

At a meeting of representatives of 6,000 blind people in Da Nang, these two met—bitter enemies driven into one another’s arms by physical tragedy and economic necessity.

Such enmity cannot, however, be solved by economic rapprochement alone. True reconciliation demands more than economic interest, just as it demands more than political concern. Reconciliation must penetrate the regions of the heart.

Ho Chi Minh City—Spiritual Reconciliation

Saigon (renamed Ho Chi Minh City by the North Vietnamese) is one of the last places on earth one would look for signs of spiritual activity. Spurred by the fertile resources of American G.I.s, prostitution, gambling, and black-market trading flourished here during the war.

In spite of its unsavory reputation, Saigon did have a vital Christian presence. A strong Christian and Missionary Alliance Bible school operated for years. Evangelistic campaigns found receptive audiences among both Vietnamese and Americans.

Still, I went to Vietnam in general, and Saigon in particular, knowing I’d find a church gasping for air under the suffocating blanket of communism. I even committed the primo journalistic sin—I wrote the lead to my story on the airplane ride over.

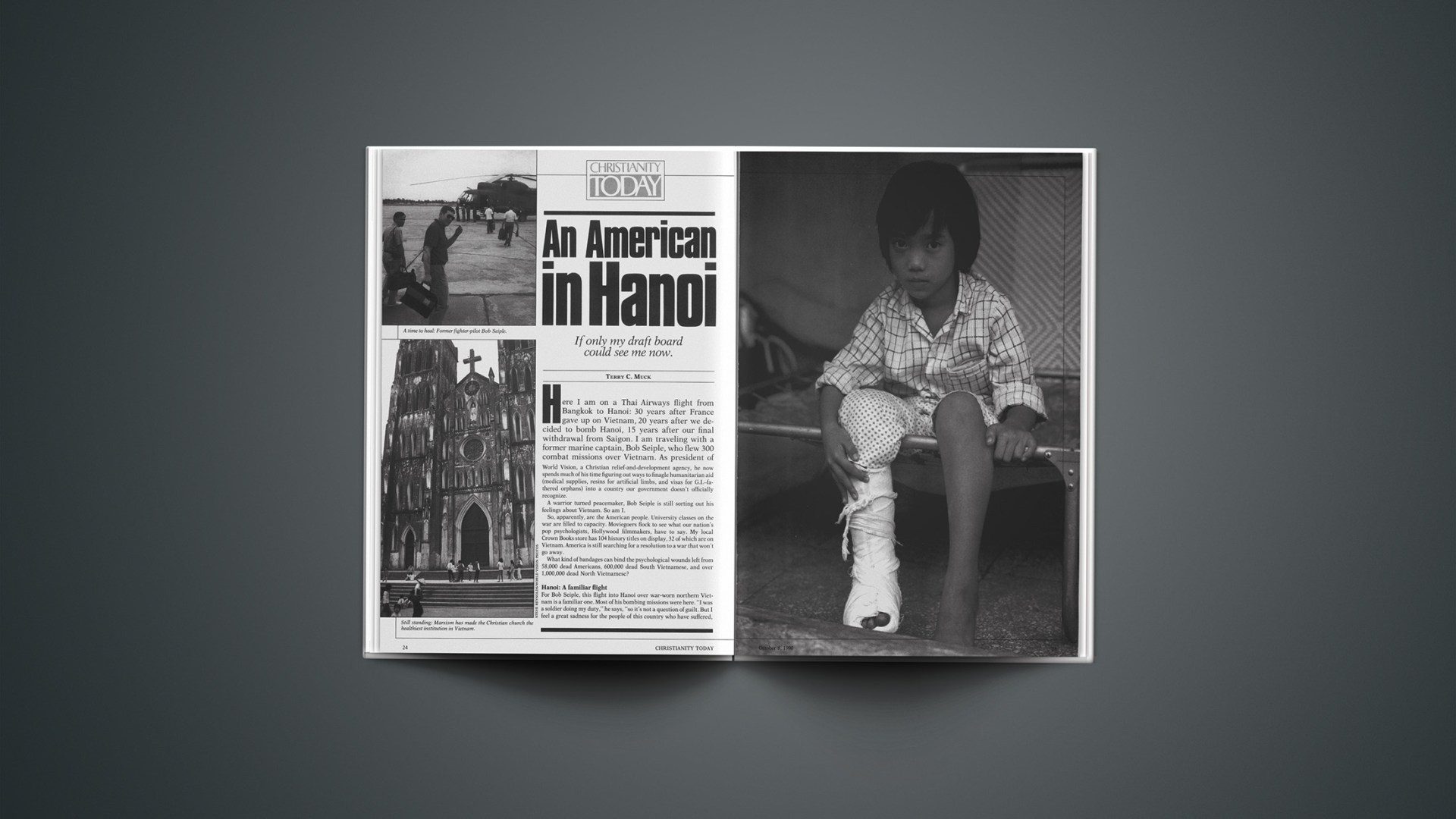

I was wrong. The church is indeed oppressed. Being a Christian often means sacrificing career and creature comforts. But the church is doing very well, thank you. Estimates of the size of the Protestant church in Vietnam in 1975 were usually around 100,000. Today, 15 years after all Western missionaries were forced to leave, after the government made being a Christian the social equivalent of having AIDS, the church has grown to 300,000 members. Marxism has made the Christian church the healthiest institution in the land.

We visit a large Roman Catholic church on Sunday evening. Thousands fill the sanctuary. Others, unable to get a seat inside, stand 20 deep outside, listening to the service on loudspeakers, straining to catch an over-the-shoulders glimpse inside.

I visit a Tin Lanh (Good News) Protestant church. I hear, through a whispering translator at my side, a stirring gospel message. I talk to pastors who tell me of growth and commitment. (They talk to me, although if my visit is observed they will surely be visited the next day by government officials.) Stories of God’s grace are told with an almost happy nonchalance by people who have come to grips with the fact that they may be called upon to suffer for their faith. They have somehow learned that suffering is not the worst thing in the world—disobedience to God is the worst.

Professor Nguyen (not his real name) went to college in America. He was a Christian, but he “found it too easy to be a Christian in the United States. It was socially acceptable. If you wanted a Bible you would get 20.”

He could have stayed in the U.S. but returned to Vietnam to teach. University officials told him he could either teach or attend church, but not both. “They made me study Marxism/Leninism for two years. I quit going to church but had worship with my family at home. I did not give up my faith. On the contrary, for the first time in my life my faith grew. I began to see that the Lord had thrown me in this raging sea not to drown me but to make me clean.”

Nguyen grew in respect in the eyes of his colleagues. “I grew confident. I decided to go to church again. But after a while I was called in again and asked to stop. So I did. But I will keep trying.”

Meanwhile, he makes a difference to scores of students. He exudes energy and the joy of Christ. Of all I am privileged to see in Vietnam, Nguyen’s life and lives like his are the most convincing evidence of hope.

Our Legacy

My last day in Vietnam I wander the streets of Saigon looking for the American legacy. I find a U.S. quarter in an antique shop, I tour a military museum filled with captured F-5s and U.S. tanks, I walk on the grounds of the former U.S. Embassy, now overgrown with head-high weeds and trash. Right now the legacy is one of a lost war. We’re history.

On my flight home through Bangkok, Tokyo, Los Angeles, and Chicago, a phrase keeps running through my mind: “All we can do now is pray.”

The phrase has always bothered me. Usually it is intoned in medical cases where everything possible has been done to save a life, but nothing has halted the slide toward death. I think the phrase, unwittingly, betrays our priorities. When faced with a problem, we’ll first try ordinary human measures, then pull out all stops and try extraordinary human measures, and if all else fails, we’ll pray.

Here’s our problem: We need to reconcile ourselves to the Vietnam War and the country of Vietnam. We properly pursue peace through diplomacy and economic aid. We seek resolution through movies and books, believing that if we understand the war we can erase confusion and bitterness. But the national catharsis we are looking for will never come until the hearts of men, the spiritual organs, are touched by a working of God’s grace. Spiritual reconciliation must come along with economic and political reconciliation—not as a last resort.

The Vietnamese church is ready for such an experience. Indeed, the church is to be a profound sign of peace and hope in a society without much of either. I wonder if we are?