Most of the theological writings that shaped Western society over the last 500 years cannot be found on Middle Eastern bookshelves. Few Arabs have ever read anything from John Calvin, Jonathan Edwards, or Karl Barth.

The reason is simple: Almost none of the Protestant canon has been translated into Arabic.

The dearth of Christian religious texts in the world’s fourth-largest language is especially pronounced within Protestantism, which developed in European languages such as Latin, French, German, and English. The Reformation has barely broken into the Arabic-speaking world, dominated by Islam and where most local Christians—whose numbers are dwindling fast—are inheritors of Orthodox or Catholic theologies.

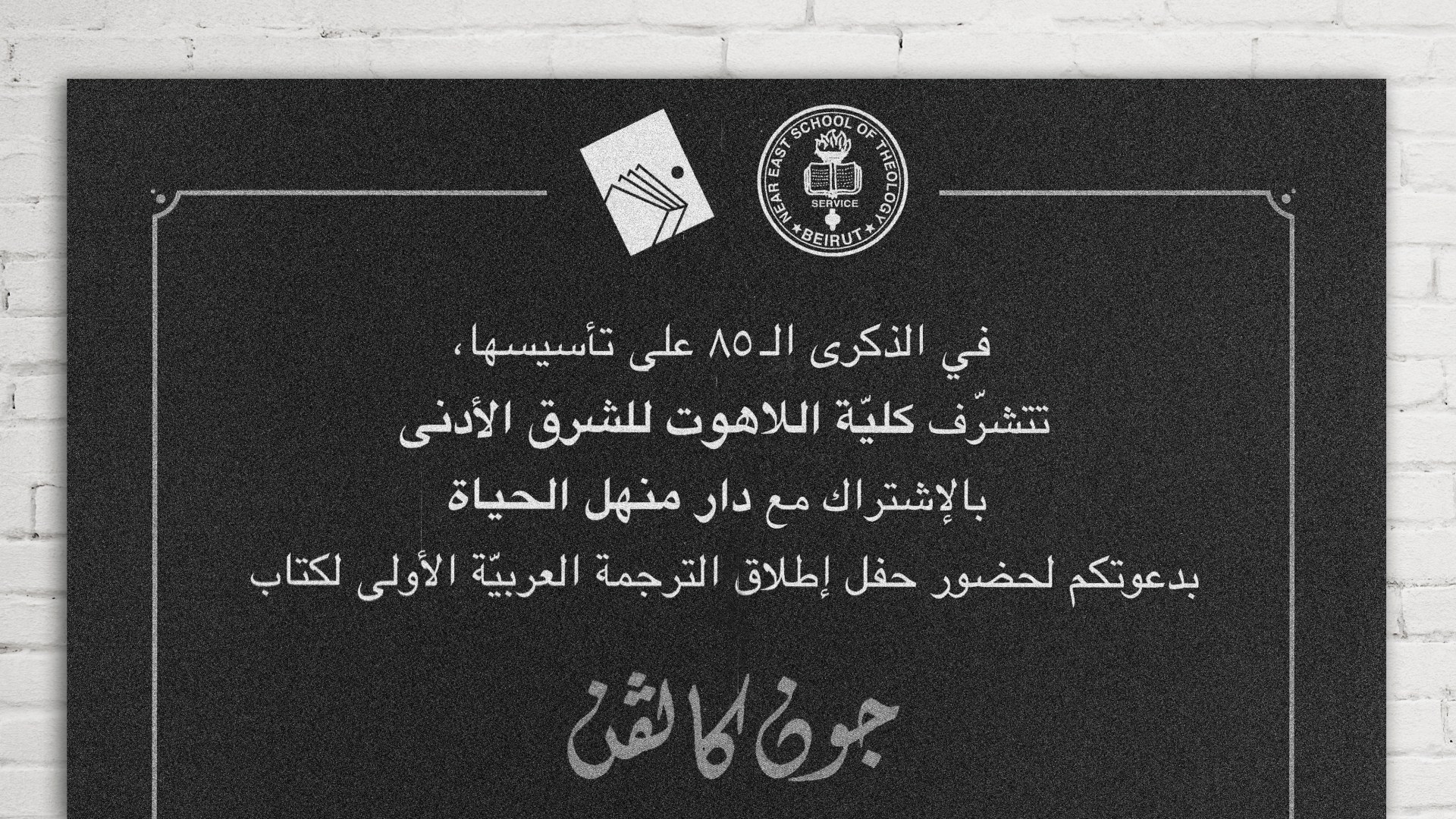

Nearly a decade ago, George Sabra, president of the Near East School of Theology (NEST) in Beirut, had the notion to translate perhaps the most influential writing of the Reformation, John Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion, into Arabic for the first time.

“It’s a major work of the Reformation, which has shaped European and American Protestantism and societies for centuries and, in a way, is still with us,” Sabra said of the French reformer’s systematic theology. “The effects of it—the whole Calvinist influence on society and in the church—are still there, even though people don’t recognize it.”

In 2008, Sabra brought the idea to NEST’s then-president, Mary Mikhael. She was receptive and helped raise funds. The process of finding a translator and ensuring consistency throughout the manuscript caused delays, but a little less than a decade later—just in time for the 500th anniversary of the Reformation—Sabra’s dream is nearly complete.

While translation efforts never stalled, for a number of reasons progress has always been slow.

First, there is little demand for Protestant theological texts in the Middle East, where the Protestant community makes up less than one percent of the population.

Second, the number of translators in the Middle East who are both linguistically qualified and theologically savvy enough to translate Reformation classics into Arabic is minuscule.

Third, Arabic is notoriously hard. Precise translation is difficult in any language, and Arabic is harder than most. Native speakers often can’t write or comprehend formal Arabic writing, and many educated Arab Protestants prefer to study in English or German anyway.

And fourth, even if the demand and translator talents were sufficient to warrant the work, who would publish it? The best Arabic publishing houses are Catholic and wouldn’t print a work like the Institutes (the sharp-tongued Calvin called the pope the Antichrist and described Mass as an “abomination”). And Islamic presses have little interest in publishing Christian theology.

After years of checking thousands of footnotes, Sabra—who settled on a Baptist publisher based in Egypt for his 1,500-page tome—has realized the weight of clear, quality translation. But he’s not the only one counting the cost.

For Middle East Catholics, less than one percent of key texts are available in Arabic, said John Khalil, a priest who works at the Dominican Institute for Oriental Studies in Cairo. “Our bishops can access works in Italian or French,” he said. “But having nothing in Arabic results in fewer theologians. It is a problem.”

Khalil recently secured permission to publish translated and original Christian works, naming his imprint after Aquinas. He has begun revision of the Summa Theologica, translating volume two and hoping to complete the rest in the near future.

But the problem is not just with the classics. Few modern theological works have been translated into Arabic either. Only one book is available from the leading theologians behind the Second Vatican Council.

Khalil’s primary interest is social justice, and in May he published the first Arabic translation of Gustavo Gutiérrez’s benchmark A Theology of Liberation. A handful of books about liberation theology exist in Arabic, but until now, no original texts.

But even these pushed Christians toward participation in Tahrir Square demonstrations that led to the overthrow of Egypt’s government in 2011. One celebrated martyr of the revolution, Mina Daniel, was a leader in Khalil’s study group.

Since then, however, many Christians have soured on such theology. Khalil hopes translation can make a difference.

“I don’t imagine we will become like Latin America,” he said, “but I hope we will at least stop blaming our young people who are struggling for justice. Religion should criticize every political system, and the church must have a prophetic voice.”

But stirring a prophetic voice can take time. The Arabic translation of the Institutes was supposed to be ready in two years. It took almost ten to be ready for its planned release last month.

“Foundational Protestant texts, as well as other scholarly Christian works, need to be translated into Arabic for a number of reasons,” said J. Dudley Woodberry, senior professor of Islamic studies at Fuller Theological Seminary.

For one, “more Muslims have become Christians in the last 35 years than in all previous centuries since the foundation of Islam,” he said. “But they do not have a Christian background to support their newfound faith.”

Also, many of these converts have come to faith through such means as satellite TV or the Bible passed along via cell phones. So a greater depth of understanding is needed, he said.

Lastly, many Arabs—both Christian and Muslim—have attended schools established by Protestant missionaries. “They are appreciative of Protestants and want to know the theology that led them to such sacrificial service,” he said.

Translation isn’t only good for understanding history; it also lays the groundwork for the future. “Historically, most of the schools of [theology] emerged out of translation,” said Martin Accad, chief academic officer at the Arab Baptist Theological Seminary in Beirut. “The translation movement creates a vocabulary in the receiving language, which can then be used in order to express theological thinking more adequately in that language.”

Like many Arab Christians, he wants to see a generation of believers who “think theologically” in Arabic and write in Arabic. “We need to find our voice in the Arabic language. Often, translation can help in that direction.”

Griffin Paul Jackson is a Chicago-based writer. Additional reporting by Jayson Casper.